This is an ongoing series by Chris Davidson, our poetry editor. Entries for Weeks 1 and 2 can be found here.

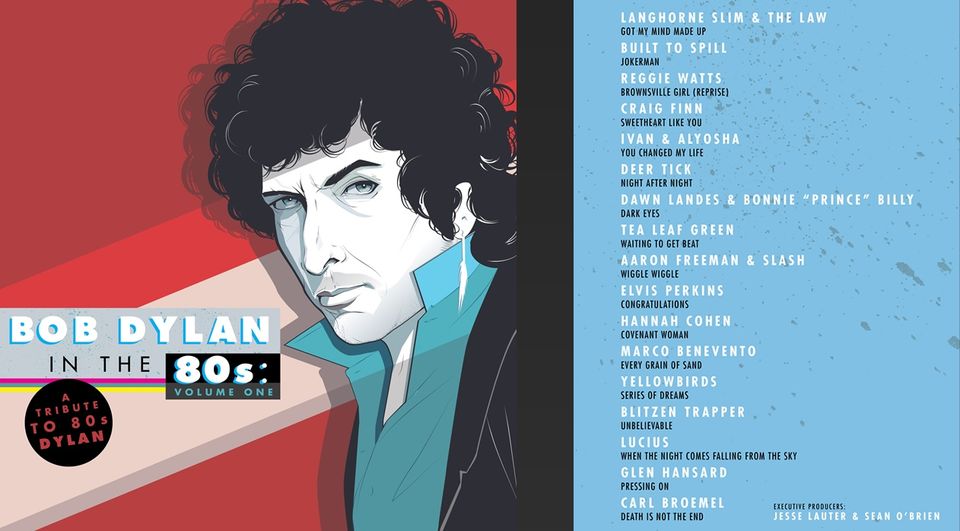

The first Dylan album I bought was Oh Mercy, on cassette, right after it came out. Reviews, which I’m a sucker for, called it a comeback for the man from Hibbing, so I drove to the San Clemente Wherehouse, bought it, unwrapped it, and popped it in the deck of my ’82 Tercel. This was in September of 1989, a few weeks before I headed back to college for the year. I therefore take it as somewhat of a cheat that Bob Dylan in the 80’s: Volume One includes two songs from 1990’s Under the Red Sky. One could argue that Dylan wrote “Wiggle Wiggle,” one of those two, sometime in ‘89, and that the cumbersome recording process held up its release till the next year. I don’t buy it. “Wiggle Wiggle” sounds like it was written ten minutes before it was tracked. No matter. Bob Dylan in the 80’s with Two Songs from the ‘90s doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue.

That definitional looseness should give the assembled artists room to have a little fun, and several of them do. For example, “Wiggle Wiggle” (note that I’m repeating that title, “Wiggle Wiggle,” as often as possible), is a bit of amusing drivel livened up by Slash’s transistor radio guitar and Aaron Freeman’s Dylan impression. He’s not the only one aping Dylan here. Like an actor in a Woody Allen movie taking on the director’s tics and delivery, some of the impressions land, like John Cusack’s in Bullets Over Broadway, and some don’t, like Kenneth Branagh’s in Celebrity. I leave it to the listener to figure out who’s who.

Bob Dylan in the 80s came to me from a student as thanks for a letter of recommendation. I was happy to get it. It’s a mild thrill to receive something solid and tangible, instead of, say, a gift card. And a music compilation has its own particular charm, like receiving an anthology of poems, or a box of chocolates. You may not like everything in it, but you’re bound to be surprised here and there by something tastier than you expect.

Nevertheless, any tribute CD post-2010 is a strange object. Consider the album under review. Although a lot of energy went into corralling the performers and creating the artwork and mastering and distributing the thing, and although it has a strong hook—digging up gems from Dylan’s lost decade—its reason for being is unclear. Who is the intended audience? The hard-core Dylan fans I know want to hear him sing his songs, not someone else. And most people under thirty-five are not going to pick this CD up. Some might listen to it on Spotify and choose a few tracks to add to their phones—and yet the point of a tribute album is to hear, side by side, different takes on the same body of work. Perhaps it was aimed at those in line at Starbucks, enticed into an impulse purchase by the rack of CDs next to the cash register, but the coffee chain got rid of those racks in 2015, shortly after Bob Dylan in the 80s was released. It’s possible that songs from the album were played on local NPR affiliates, who then offered it as a premium during membership drives, but I can’t imagine Bob Dylan in the 80s ever flying off the shelves. For the producers to put all that time and effort and money into making this CD as CDs face rapid extinction is an act of irrational, endearing hope.

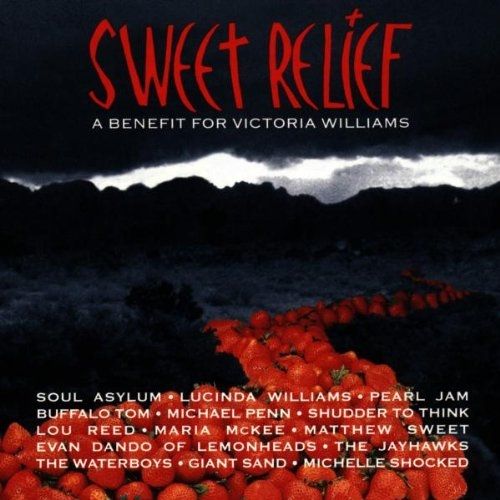

The first tribute album I got was Sweet Relief: A Benefit for Victoria Williams, from 1994. This is a perfect example of the form. It had purpose, in that it was pulled together for the sake of the songwriter it celebrated, who suffers from multiple sclerosis and, as a low-selling but highly respected musician, lacked health insurance to help manage her condition’s expenses. It launched a charity that to this day helps struggling musicians pay medical bills. It featured a healthy mix of artists, from alt rockers at peak fame to roots revivalists in the rising-in-popularity but hideously named Adult Album Alternative Radio, from college-rock mainstays to revered veterans. It introduced to a wider audience a songwriter whose voice, an acquired taste, kept fans away from her concise, wise, and generous songs. And it landed Williams a new record deal.

Dylan, on the other hand, has had a record deal for fifty-four years, and none of the artists on Dylan in the 80s lights up the marquee like Pearl Jam did two decades ago. Instead, they read like a Pitchfork dream team, before Pitchfork discovered hip hop and Carly Rae Jepsen. Built to Spill’s serviceable “Jokerman” doesn’t reach the aurally majestic heights that band so often reaches, but it’s still a great rock song. Craig Finn’s “Sweetheart Like You” is a lovely ballad that would fit right in as the fourth track of any Hold Steady album. Deer Tick’s “Night after Night” is a charming Jimmy Buffett homage, complete with electric piano and boozy tempo. Reggie Watts’ “Brownsville Girl,” though not as inspired as his riff on Van Halen’s stupid and irresistible “Panama,” reminds the listener that Watts is not just a comedian—he’s a singer of surprising range and a master of sonic trickery. An outfit named Ivan & Alyosha (I get that reference!) turn in a sincere, harmony-driven version of the castoff “You Changed My Life.” (Their version is good, but I prefer the original, with its remarkably propulsive drums and Dylan’s sneering delivery of lines like “You do the work of the devil, you got a million friends / They’ll be there when you got something, they’ll take it all in the end.”) Dawn Landes sings a gorgeous “Dark Eyes,” with Bonnie “Prince” Billy, resplendent harmonist, in accompaniment. In short, this is an excellent listen.

If none of these titles rings a bell, don’t worry. That’s the point. Nobody’s heard of them. As the story goes, the ‘80s were a bad time for Bob Dylan. I mean, look at this album cover! Who let him dress like that? Yet this project demonstrates that Dylan’s weak output might have been a matter of context as much as quality. He’d been recording for twenty years, having released twenty albums. Like Neil Young, at roughly the same time, he tried out different clothes, recording techniques, and backing bands out of…what? Boredom? Desperation?

At the beginning of his career, Dylan was called—by marketing agents, by journalists, by someone—the voice of his generation. Despite his protestations, the identity stuck. After twenty years, a few years shy of the demographic definition of a generation, those Dylan “spoke for” found themselves, like him, in their 40s—working, having families, spending less and less time on leisure. In a few years, they’d have the means to shell out $200 to go see him or the Stones or Paul McCartney in concert, or $1000 to see them all at once, a reward for their years wandering the desert of domesticity. In the meantime, what was Dylan to do? Wake up and go to work, just as he had since 1962. His harried fans, who used to buy records and march in the streets and burn their draft cards now had mortgages to pay and kids to raise and minivans to buy. Heroes are for the young. Hence Dylan’s dressing like Don Johnson in Miami Vice. Hence his flirtation with hip-hop and drum machines.

Of course, this kind of pop sociology is based in mere conjecture, since I’m no historian and I don’t pretend to know what Dylan thinks. In the 80s, my understanding of Dylan and the counterculture was limited to a) hearing “Like a Rolling Stone” a whole lot on classic rock radio, and b) occasionally seeing on TV metonymic images of youthful unrest meant to signify “The 60s.” Still, I like to think of Dylan worrying about his slipping audience and thus buying into fads meant to appeal to younger fans. Such grasping makes him more human, somehow. You could argue that Dylan’s subsequent artistic rebirth happened when he remembered what he already knew: That to seek for relevance is a mug’s game. The real pursuit, as for the poets of old, is immortality, which meant Dylan had to reclaim—sonically, visually, persona-ly—his mythic identity. Beginning with Oh Mercy, his sound and wardrobe returned to the roots-oriented, old timey-ness of the Basement Tapes era, though now he had the grizzled countenance to match the threads. Returned from his sojourn through banality was the mysterious man in the alleyway, present but unknowable. For evidence, look at this post-performance interaction with David Letterman, from 1984, and this one, from last year. In 1984, he interacts with the host, and even laughs at his jokes. In 2015, he’s aloof and distant, a resident of Olympus, come down to bless us with his presence.

That’s why some of the best stuff on Bob Dylan in the 80s is either irreverent toward its source, like the Watts performance, or drawn from his born-again phase. Beginning in 1979, the artistic genius, the beat-poet hipster, the man apart sang about sin and salvation and the person of Jesus Christ, and he seemed to believe the whole thing, from Genesis to Revelation. If you’ve seen No Direction Home or Don’t Look Back, you know that one aspect of Dylan’s genius is his refusal to be pigeonholed, to explain what his songs mean or what he means. It’s poignantly sad to hear his aged protest-singer peers lament Dylan’s moving on to a less easily defined set of goals, betraying (for them) the cause their music served. For Dylan, “art” was the cause; it was not subordinate to a political movement. As soon as you let your work be used for a movement, you’re subject to its leaders’ exploitation and eventual irrelevance.

Dylan’s born-again period is fascinating because he willingly let himself be pigeonholed, subordinating his art for an easily ridiculed cause: Evangelical Christianity. It was gutsy of Dylan, in 1960, to give up his name and fabricate his history on the way to Greenwich Village and the subsequent renown he’d achieve. It was arguably gutsier, in 1979, to risk that renown by singing of ideas handed down by tradition instead of forged in the Blake-ian heat of artistic creation. Christian faith demanded of Dylan the kind of personal definition he made his name evading. It also meant that Dylan hitched his wagon to a movement associated with obnoxious, power-hungry men using the subjects he sang about to condemn whole swaths of the American electorate.

Alas, it was as short-lived as his tenure singing protest songs. Yet whatever beliefs Dylan held in 1980, the subsequent decade is pervaded by his encounter with (what he claimed at the time was) the sacred. What these songs lack in innovation and vision, especially when compared with his mid-60s output, they make up in sincerity and a belief in transcendence that predates by ten years David Foster Wallace, Paul Thomas Anderson, and The Soft Bulletin. You can hear it in “Ring Them Bells,” from Oh Mercy, and “God Knows,” from Under the Red Sky, and it pops up again and again in Bob Dylan in the 80s, which ends with a lovely three-song suite about reality, resolve, and peaceful resignation. The marvelous Lucius perform “When the Night Comes Falling from the Sky,” a song about frail human relationships that also manages to celebrate and reassure us about the approaching, implacable darkness. Glen Hansard brings all the shameless earnestness he brought to the movie Once with “Pressing On,” a song of devotion and will that builds in power as it unfolds, like a religiously-backed “Invictus.” And Carl Broemel’s lovely, nasal tenor, along with a ghostly choir of multi-tracked voices, ends the proceedings by insisting, without hectoring us, that “Death is Not the End.”

Ahh, but this review is at its end. In the few words I have left, I’d like to say—to my former student Nathan who gave me this CD, to the producers of this foolishly devoted project—thank you. I’ve played it and thought about it. I’ve felt better about life each time I’ve listened to its last three songs. And now I’ve written about it. It’s lived on beyond its making.

[Next week: Fishbone, Truth and Soul]