I am not the sort of person who flips through pictorial medical dictionaries to pass the time. I can’t believe sites like Dictionary.com and MySpace post ads for toenail fungus medicine, and even if I scroll down before the toenail lifts like a trapdoor and the cartoon bug squirms out, I still feel queasy. This summer, though, my husband considered it serendipitous that we were traveling to Philadelphia right after we watched Errol Morris interview Gretchen Worden, the late curator of Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum.

And so, I found myself browsing a collection of over 20,000 anatomical and medical objects, most of them from the nightmarish realm of pathological anatomy. The Mütter museum claims to tell stories about the human experience, and as I swallowed my squeamishness and faced specimens in jars, I realized the morbid collection resonates with Christian ideas of truth, goodness, and even beauty.

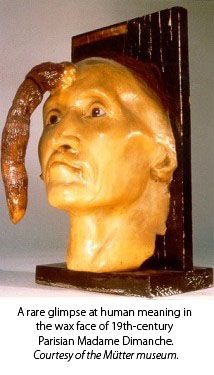

This singular museum began in 1858 when Thomas Dent Mütter, surgery professor at Jefferson Medical College, offered his personal collection to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. The museum, located in Rittenhouse Square, exhibits 2,000 objects extracted from people’s throats, a wax model of an elderly Frenchwoman with a long, downward-curving horn growing from her forehead, a plaster cast of famous twins Chang and Eng who were conjoined at the sternum, and the blackened corpse of the “Soap Lady,” who was mummified as her body fat turned to soap around her.

In the galleries, the ravages of leprosy, syphilis, tuberculosis, cancer, birth defects, and many other diseases and abnormalities are behind glass, floating in jars, or cast in wax or plaster. They are unsettling and informative. Pre-Mütter, I had never heard of cutaneous tuberculosis and had no idea the disease could wreak such havoc on a human face-small, pervasive lesions, what look like large red burns, and noses melting away into masses of blood and scabs. I had never seen pictures of smallpox and had no idea that its lesions cover the entire surface of the skin, making faces look like rocks packed full of barnacles, making chests and arms look like a swarm of beetles, and leaving barely anything discernible as human skin.

Specimen after specimen, the galleries can become a bombardment. For me, the images did not arrange themselves into what the brochure had promised-stories about human meaning-until I saw a glimpse of beauty. On a high shelf, the bust of a striking young woman was displayed. Her statue could have been mistaken for an ancient Venus, with the same discreet, downward cast of her eyes and youthful softness of flesh captured in the plaster cast. She could have been mistaken as such, if not for one thing: a tumor the size of a grapefruit on one side of her neck.

It was in seeing this beauty so almost whole that the bombardment became a solid question: what did we do to ourselves in Eden, that we walk around so beautiful and so damaged? It is rare to see the effects of human brokenness all lined up in tidy, dust-free rows, carefully curated with expository tags. It is rare, and vital. This is the human story, behind glass, in its most extreme edges.

These ravages are extreme. But some of us have experienced them, and we must hold onto this. We are prone to hide these things. As a child will hide the smashed vase, we hide the way original sin has broken humanity. We build mental institutions thick and high; we incarcerate old age and deterioration. We recoil rather than face what Eden has done.

Is it because we know that even if our skin is unblemished and our bodies comfortable, this suffering is still our story, one of souls scabbed over, personalities riddled with pocks, psyches melting away? Augustine wrote that we carry within us the witness of our sin. Mütter’s specimens are synecdoche for a whole catastrophe.

We are all grotesques, Flannery O’Connor used to say, even though some of us may not realize it.[1] O’Connor believed that ours is an age “whose deafness requires the raised voice,” says Ralph C. Wood, “and whose blindness demands large and startling figures.”[2] Like a Flannery O’Connor story, the Mütter Museum shouts. It rakes up emotions. “People talk about being ‘grossed out,’ ‘appalled,'” Gretchen Worden told Errol Morris. “Whatever emotional reaction you have, that’s good.” [3]

This is a tour of the Fall, and seeing the effects of humanity’s sin calls for a response that is visceral, not just intellectual.

The Mütter Museum does, unselfconsciously, provide some respite from the bombardment. Looking closely at some of the faces and reading the stories that accompany some of the models shows that damage is not the whole tale.

Take, for instance, the dignity of the young girl shown in two black-and-white photographs in the Mütter collection. She supports herself on her hands, as if she is a gymnast maneuvering on the horse. She supports herself like this because she has no legs. And yet, even as she is being photographed, she looks peaceful, determined. She is a child, probably about ten years old, with her hair pulled back in a ponytail, and yet in her concentration and the calm aura of the photograph she has assurance that some adults haven’t managed.

The landscape of the Fall is not just the landscape of despair but the landscape of redemption, one where we see “hideous beauty and beautiful deformity”-to borrow the phrase Bernard of Clairvaux used to describe the religious art of his day. [4]

Looking at the girl in the black-and-white photographs, “you don’t get the sense of any deformity,” Worden told Errol Morris. [5] Her carriage is graceful. Her spirit shows that there is grace in the abyss.

[1] Muller, Gilbert H. Nightmares and Visions: Flannery O’Connor and the Catholic Grotesque. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1972, 7.

[2] Wood, Ralph C. “Flannery O’Connor’s Witness to the Gospel of Life.” Modern Age Fall 2005: 321.

[3] Morris, Errol. “Smiling in a Jar.” Errol Morris’ First Person: The Complete Series. 60 min. MGM, 2005. DVD.

[4] Muller, 2.

[5] Morris.