I’m not from the South, and I had never been to a Mardi Gras parade until I moved to the Gulf Coast of Alabama. For me, Mardi Gras had no real caché – I’m not Catholic, was never big on drunken parties, and had no desire to swap a peek at my body for beads or anything else. It was just a big party in New Orleans, and though I frequently observe Lent, I never planned to attend Mardi Gras.

But then I moved to Mobile, the birthplace of American Mardi Gras, and have since learned more about the holiday than I ever thought I would. Most importantly: Mardi Gras did not originate in New Orleans, though that city has since taken the whole celebration over and perverted it beyond its original intent. The first Mardi Gras celebrations in America were in Mobile, Alabama, where I currently reside, which was the capital of the French colony of Louisiana in the early 18th century. The first Mardi Gras celebration, in 1703, was a means for the French colonists to remember their homeland roots. It wasn’t until 1720 that the Louisiana capital was moved to New Orleans, where Mardi Gras was adopted. Compared to the civilized and well-organized Mobile Mardi Gras celebrations, the New Orleans celebrations were mere gatherings with no organized activities. The people just celebrated in whatever way best suited them.

When I learned that Mardi Gras was celebrated here in Mobile, I wasn’t interested. But people assured me that it wasn’t the breast-flashing heathen fest I had seen on television in the Big Easy – they called Mobile’s celebration “family friendly.” So, my husband and I headed to our first parade to get a taste for ourselves. My previous parade experiences had been limited to Memorial Day and Fourth of July parades, where people would set up their lawn chairs on the side of the road and watch the parade pass. If candy was thrown, it was usually Tootsie Rolls or Bazooka Joe bubble gum, and the children would run into the street to fetch as much candy as they could. There were floats, but mostly it was marching bands, jump-roping clowns, and politicians sitting on the backs of convertibles. Mardi Gras is nothing like this.

Huge crowds gather into mosh-pit-like packs, and there’s nowhere to sit. Massive floats make their ways down the street, one after another, with “throws” tossed into the crowd – anything from beads and moon pies (a Mardi Gras favorite) to stuffed animals and cups. The floats are usually linked thematically – for example, last year we went to a parade themed “The World Loves a Clown,” with floats ranging from Batman’s Joker to Krusty the Clown – and costumed revelers stand atop, throwing their various goodies. Marching bands and dance troupes break up some of the madness, but everyone goes to the parades for the throws.

And it is a lot of fun. People in the crowds yell and wave their hands and bump into each other. They grab and horde and what surprised me is that they also share, something I learned from a young boy who gave me a stuffed animal he had caught because he knew I didn’t want any more beads. The only real rule is to pay attention and keep your hands in the air, ready to catch anything thrown at you, which we learned the hard way after my husband was given a bloody forehead by a wayward cup.

But Mardi Gras is so much more than the parades. There are more than fifty Mardi Gras mystic societies, each autonomous of the rest, with new ones added every year. Each holds a reception or ball, and about twenty-five hold their own parades. Associations require dues from each member, as well as attendance to regular meetings, float building, and sometimes, fundraising. Many associations have a waiting list – some of the more coveted have waiting lists of up to ten years – and often membership is passed from one generation to the next. Members ride on the floats, dressed in costumes with masks so that no one at the parade can identify them. The Mardi Gras balls are often exclusive or semi-exclusive, requiring nonmembers to have an in with a member in order to get a ticket. At the balls, members dress in character or the men wear tails and women wear evening gowns.

Then there are the kings and queens. The city celebrates Mardi Gras in two carnivals – the Mobile Carnival Association (MCA) carnival and the Mobile Area Mardi Gras Association (MAMGA) carnival – and each chooses a king and queen. MCA’s “royalty” are white, while MAMGA are African American. Queens are drawn from a pool of debutantes, the rest of whom become the queen’s ladies in waiting. Each lady in waiting chooses her own knight, usually her boyfriend, to accompany her to Mardi Gras functions. The MCA king is usually dubbed “King Felix III” (no matter what his real name is) and is said to “mis-rule” over Mardi Gras. The MAMGA king is called “King Elexis.” Both MCA and MAMGA hold their own functions, coronation ceremonies, and parades, though the two associations don’t usually mingle.

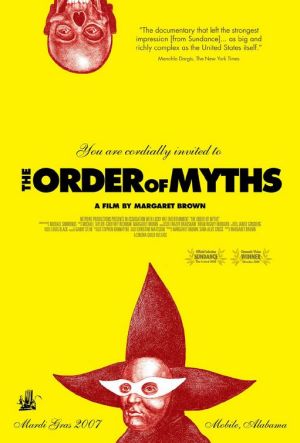

What is most surprising – or maybe not – about Mardi Gras in Mobile is how segregated it remains. The 2008 documentary The Order of Myths, which followed the 2007 Mardi Gras celebration in Mobile, focuses its attention on MCA and MAMGA and their blatant division by race. Most of Mobile’s parade organizations are white, with the exception of one integrated society, founded in 2003, which has only one white member. The film follows the preparations before Mardi Gras, from luncheons and parties to the extravagance and labor of the royal court’s attire to the everyday lives of the people involved.

In the film, the differences in the two sets of royalty are notable. King Felix receives a key to the city from the mayor (the city’s first black mayor), though King Elexis does not. Queen Helen of MCA is from a very old, high society Mobile family, in stark contrast to MAMGA’s Queen Stephanie, who laments her estimation of financial expense for Mardi Gras to be equal to purchasing a car. (Ironically, Queen Helen’s family owned the slave ship that brought Queen Stephanie’s family to the United States from Africa.)

The interviews with various Mardi Gras affiliates (including a few masked interviewees), which pepper the film, are where the real spirit of racial tension emerges. Most tiptoe around the issue, stating that it’s the blacks or “colored people” who want to keep Mardi Gras separate in order to retain their own traditions and roots, but it is evident that both blacks and whites are torn between sticking to tradition and taking steps to try to integrate the yearly celebration. This seemed to stem from the looming question of how to integrate, to which no one has a real answer.

In 2007, the MAMGA king and queen made an appearance at the MCA coronation ceremony, and were the first from MAMGA to do so, despite having been invited for the past 30 years or so. The MCA king and queen reciprocated by attending the MAMGA coronation ceremony the following night, and were the first set of royalty to attend a MAMGA event. This appeared to be a step in the right direction, though the MCA king in an interview later in the film seemed more interested in preserving tradition than trying to intentionally integrate, stating that it’s something that should be done in the future but not right now.

The Order of Myths offers no real answer but merely presents both sides of the celebration in order to provide fodder for conversation. Perhaps things can change. In any case, Mobilians take Mardi Gras seriously. And in spite of the racial dynamics, it is a seriously good time. The two week celebration is imperative to Mobile’s economy, with millions of dollars allocated by mystic society and association members as well as the city itself. Though much of the celebration’s framework is similar to the one in New Orleans, with the secret societies and parades, the focus of Mobile’s Mardi Gras is tradition and celebration rather than partying and drinking. Mobilians are right – it is family oriented and safe. And as a non native, what I know for sure is it’s a whole lot of fun.