Donald Kaufman reminded us, “There hasn’t been a new film genre since Fellini invented the mockumentary.” But we need an addendum to that scene of Adaptation. In the past year, two movies were released that blurred the lines between documentary and mockumentary. The more popular was I’m Still Here, the “hoax” film about Joaquin Phoenix’s downward spiral out of show-business. The more interesting film was Blood Into Wine, the story of how Tool’s Maynard James Keenan shifted his attention away from rock and roll and decided to create a winery in the Arizona desert.

Neither of these films are documentaries in the traditional sense. Ken Burns probably wouldn’t endorse either of them. Documentaries, as Michael Moore boldly claimed when he won his Oscar, deal with non-fiction. I’m Still Here and Blood Into Wine are unclear in where their “non-fiction” is based. And yet, they are not exactly Guestian mockumentaries either. There is reality inherent in these films, in spite of vehemently false aspects. Let’s call this new genre, the meta-mock.

Postmodernism triggered a self-conscious ambiguity in film. Zizek asserted that the virtual is now the reality, and he’s right– hence the popularity of reality television, online social networks, and this new film genre that straddles the fence of documentary and mockumentary. Due to this paradoxical genre’s simultaneously real-yet-false qualities, the virtual is more real in a meta-mock than the “non-fiction” Bowling For Columbine was.

Meta-mock is like the filmic version of Kierkegaard’s philosophy: truth is subjectivity. Just as Nietzsche and Sartre would be nothing without the existential groundwork of Kierkegaard, I’m Still Here and Blood Into Wine probably would not exist without the trailblazing of Werner Herzog. He directs both fictional and non-fictional (documentary) films, but the latter are never straight-forward. Herzog has a keen sense of what makes a subject interesting, and may linger on it for over an hour, without narration. However, he is never afraid to insert his own opinion into a story. His own subjectivity may enhance the overall quality of the film.

In Grizzly Man, Herzog decides to not reveal the video or audio of Timothy Treadwell’s bear mauling. He insists that it is too gruesome, and must not be revealed to the world. He even says that the tape should be destroyed.

What nerve.

To have non-fictional material that documents a major event in the film, and to throw it away. As a “documentary” filmmaker, how can Herzog make such a decision?

Now we can begin to see the blend. Before, we assumed that all documentaries were true, and that all mockumentaries were jokes. Meta-mock is intentionally indeterminate, and would rather leave questions out there for us to ask for ourselves than give us objective information. Herzog did not want to tell us what happened in Treadwell’s final breathing moments; he wanted us to imagine it instead. What is this material that is so horrific that it cannot even be seen or heard on film? Truth is subjectivity.

In Adaptation, a movie that is neither a documentary or mockumentary, but is meta-aware of its guile, Charlie Kaufman toys with what a film means to reality. Is it meaningful? Is it true? What do we come away with in the end if not a fleeting feeling of being entertained? In meta-mock, these questions are cornerstones, but are altogether more introspective. Appropriate to their content, the major theme in both I’m Still Here and Blood Into Wine is self-discovery.

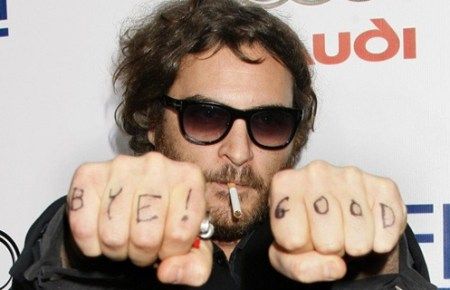

I’m Still Here is about one man: Joaquin Phoenix. His character believes that to be himself, to follow his dreams, he must give up acting to pursue the art of hip hop. It doesn’t matter that this isn’t the true desire in Phoenix’s physical reality, because it is the true desire of the character in the film. Every protagonist has a desire. This is another reminder from Adaptation‘s McKee.

The protagonist in I’m Still Here goes about his journey in an important setting: the real world. Camera phones, blogs and real human eyes perceive this not as a performance piece, but as an actual man who has lost his mind. Have they been tricked by Phoenix? Not really, because his performance was intended for the film all along. The final product needed real camera phones, real blogs and real human eyes. The character wanted to take a journey of self-discovery, not simply trick consumers of popular media. How can you discover your self if not in the setting of real world?

Unfortunately, most critics missed the point. They felt tricked. They thought this was some sort of attempt at a post-Andy Kaufman stunt. But where Andy made his trickery a 24/7 gig, Phoenix was only playing a single role for a short amount of time. Andy was also a comedian. Phoenix is not. Big, big difference.

I’m Still Here is a movie about embracing individual reality. Did the Phoenix character find what he was looking for? That’s for the viewer to interpret. But the more important question to ask is, are we on similar pursuits? Are we being true to ourselves, or are we fooling ourselves? What does it mean to be an actor? What does it look like when we’re faking it?

Blood Into Wine asks these same questions, and self-discovery is also at the film’s core. But this film lets the forgeries roam freely. Tim and Eric open the film as the hosts of a fake talk show called Interesting Things, in which they ask Maynard questions about his winery. Right at the start, real and fake are colliding in a meta-mock world that can only exist in cinema.

Throughout the film, recurring disorientation pummels the viewer by way of new age healers, comedians and gag scenes that cause us to question the non-fiction aspect of the whole thing. Everything that is intentionally supposed to look real, (the wineries, interviews, product designs, etc.) does look convincingly real.

Is it really real though? There are staged scenes, that is certain. But where is the reality?

By the end, just when we think that there really might be a winery in Arizona run by Maynard James Keenan, he looks at the camera and says, “Who knows what happened when the camera was off? We could have set up this whole thing. This could all be bullshit… As soon as the camera’s on, people act different. That’s the nature of reality TV. This may not be how I am.” Why would he even need to say that if everything is real? Because this is a meta-mock. Its joke is on itself. It knows that it’s not reality and yet, there is still communicable life and inspirational power in those recorded sounds and images. The viewer is in real existential reality, but that LCD/Netflix mirror in front of us is there to help us question ourselves.

As the father of meta-mock (Herzog) propounded: “Ecstatic truth. I’ve always tried to strive for a much deeper truth in the images, in cinema, in storytelling, on a screen, so whether I’ve achieved it or not remains to be seen…” Only through subjective eyes may we see it. And in this way, welcome our newest film genre–the meta-mock.