A winding phone conversation between Meaghan Ritchey & Matthew E. White, the man behind “The Big Inner” and SPACEBOMB in Richmond, VA.

Meaghan Ritchey: This is Meaghan from Curator Magazine.

Matthew E. White: Yeah, it’s good to hear your voice.

MR: I’m jumping right in. Great emphasis is put on your lyrics. I think that your narrative form will resonate with our readers, I do, but I want to be deliberate about the instrumentation on Big Inner because it’s incredible! Can we talk about a few instances that struck me? Can I get specific right off the bat?

MEW: Yeah! Sure.

MR: Is it Phil Cook playing piano on Big Love?

MEW: Yes.

MR: How did you meet? And how much of what he did on that song was intentional?

MEW: We happened to be in two bands that were playing the same show one night in Nashville—it’s been a long time, 7 years ago now—and it took us 5 minutes to realize we were connected in a very soulful way. We’ve worked together previously with the Sounds of the South project. Liking his vocal arrangements, I asked him to do some on my album. I also had a few piano bits I wanted him to play on, and ‘Big Love’ was one of them. My instructions were: be sort of rocky, Jimmy Hendrixy with a Jerry Lee Lewis playing piano on top. There’s just piano, and there’s blues piano, and New Orleans piano, but there’s this very particular sort of piano like Jerry Lee Lewis, Richard Manuel, and the Band— rock ‘n’ roll piano—I wanted that, and he did a good job.

MR: Yeah, he did! So up for a little more grilling? On Brazos there’s a very marked change at the end of the song. Can you talk about why you did that?

MEW: I’d written the song—up until that point it was kind of complete, or it was getting there—and I heard this lyric in this Brazilian tune called ‘Brother’ off an album in the 70s—sort of obscure —and its that “Jesus Christ is your friend”—and I liked the way the words worked over that particular chord progression in his song. Immediately I knew it would be great sort of coda ending for the record. Brazos adds a spiritual flavor, clearly, but also just a narrative flavor that made the song three-dimensional to me. It was a way for me to flesh out the narrative and pay tribute to an artist that I respect greatly and a tradition that I respect greatly. And also an instrumental platform to really ride out the record. It’s the biggest thing that happens, and I think really closes it down nicely.

MR: The melodies immediately draw you in and force you to pay attention to the lyrics. What are some musical experiences that have done that to you?

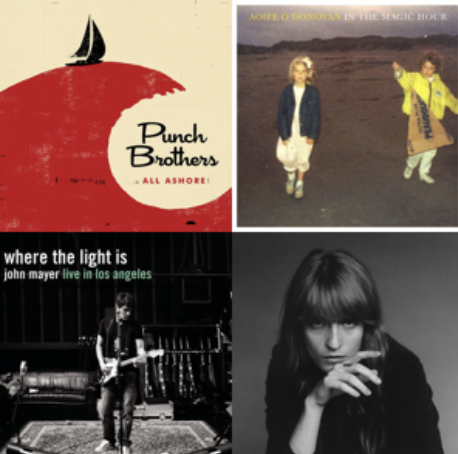

MEW: Umm that’s a good question (laughs). Let me look at my CD shelf. You mean sort of like records that I’ve sort of have fallen in love with from the get-go?

MR: Albums that like on first listen have grabbed you, with an understanding of the fullness of the lyrics coming thereafter?

MEW: Unfortunately this album doesn’t have lyrics, but Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew was the record that changed my life. I didn’t get the complete scope of it the first time. Listening to it more I realized it was something sort of transcendental. Now, something with lyrics? Maybe uh—that’s interesting—you know I’m sort of a lyricist by accident. It’s funny that you mention people pay the most attention to them and if you asked me what my strengths were that is not what I would answer. I’m still trying to think of a record from before…you know there’s a lot of soul records! Let’s say Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On”—that’s a good record to think about. Actually Outkast is a good example! Like hip hop stuff because it’s so vibrant rhythmically, you sort of just like go with the flow—whatever they’re saying.

MR: That’s how I feel about Wu-Tang. (laughs) Like despite myself, I go with the flow.

MEW: …then you start thinking about the words and then you’re like: they’re saying real stuff, about life and death, and culture, and society, and wealth, and poverty. Do you want to know the best example? (The man’s mind running) Gospel. The way people listen to gospel music is funny. Some turn it on as party music or fun background music, but it’s incredibly religious.

MR: And it’s incredibly participatory.

MEW: It’s not under the covers at all. It’s just religious. Never in a million years would you turn on praise and worship music from the 1990s, or play it in the background for just like fun. When I hear friends of mine that are non-religioius listening to black gospel, they act like it’s Bob Dylan. Because it’s so good. Don’t laugh, that’s sort of a weird example.

MR: It’s the right kinda example.That’s actually helpful because it touches on how we participate with music—how we can be both passive and active listeners, how the function of music changes based on setting and audience.

MEW: It’s kind of a blessing and a curse. What’s interesting is the racial element there, too. Non-religious, white audiences don’t give the same sort of seriousness —at least not the intended seriousness to gospel music. There’s an irony in listening to it for them, or something.

MR: I lived in Harlem for a while right by the legendary Abyssinian Baptist Church. It seems like the same reason hundreds of European tourists line up outside for performances (tailored for them) that aren’t worship services. They’re watching, but participation isn’t there, never a drive to stand up, clap, weep, even sing along, which mystifiesme.

MEW: (overlapping Meaghan) Yeah, that’s weird. There’s weird racial stuff going on in there that I don’t want to get into. (Laughs).

MR: Me either!

MEW: It’s a little weird. And I figure a little touchy. I wouldn’t be comfortable going into it too much, but when practices aren’t attached to their cultural context—I don’t know—to me they lose a level of seriousness. I think that’s troublesome. In instances like that, white culture almost becomes a caricature of itself while it caricatures others. Shouldn’t what’s serious in black culture be taken seriously in white? At least far as these worship practices are concerned?

MR: It’s pretty exciting to me that you brought this up because it’s one of the things I was thinking about before I started to prepare. I mentioned it to a friend and he said, “Meaghan you can’t go there, that would be weird. And difficult to talk about.” It was triggered by my thoughts about Richmond. I just wondered if it affected you… having an audience composed of a certain “type” of person—as bad as that sounds—when you’re performing music steeped in a tradition that isn’t theirs?

MEW: The audience is how you’d imagine it. Richmond is very divided—it’s not like violently divided—but demographically there’s a black part of town and a white part of town. Richmond was the capitol of the Confederacy. Richmond was a gospel mecca, but no one knows that here. There’s these huge black churches here that have amazing gospel choirs. On Sundays I’d attend and be one white guy in a room of 5,000 black people. One time—not on purpose or else I wouldn’t have gone— I was there on the Sunday after Coretta Scott King died. The church was singing freedom-type songs, civil-rights spiritual play: “We Shall Overcome”. I thought: What am I doing here? I’m here intentionally. Working in Richmond, I hope to have the resources, time, and courage to go into that uncomfortable world and explore it.

MR: Were you intimidated? Or were you just overwhelmed?

MEW: I wasn’t intimidated. No one made me feel like I shouldn’t be there. But it isn’t my history, you know? There’s an African American history that is strong, powerful, sensitive, and sacred. To be perfectly honest, if we’re talking about granddads, like the guy next to me—like your granddad and my granddad—that’s not going to be a pretty scene. I try to be really sensitive about it. That’s what Brazos is about.

MR: Maybe one day I can come back to this subject with you? You mentioned falling into songwriting by accident. How much of your music-making is in the studio is accidental? Or do you find that a high level of intentionality gets you where you need more often?

MEW: I don’t mean that I wrote the songs by accident. The initial plan was for the record to be an introduction to SPACEBOMB and the Richmond community. I felt like I should kind of go first to demonstrate the process. We have specific production ideas, instrumental ideas, and orchestration ideas — the things we were talking about— but I didn’t have songs. The songs on Big Inner weren’t songs that were sitting around. And I don’t mean that to make it impersonal—they were just written specifically for a specific project.

MR: I think they’re more purposeful becauseof that.

MEW: I want to be a producer and an arranger, and I’m entrepreneurial, so I started a record label. But I needed songs. You can have all the great ideas in the world, but if the songs aren’t good, then the ship doesn’t sail anywhere. The songwriting part was just consulting of the rest of it. I could be a professional arranger, but as a songwriter and as a singer I’m kind of primitive. It’s sort of an adventure. And that’s fun. I like the duality of it.

MR: If you could bring anyone out to Richmond to record with SPACEBOMB, who would it be?

MEW: Anybody?

MR: Anybody.

MEW: Beyonce.

MR: (Laughs) Really? Truly?

MEW: Yeah!

MR: And not Jay-Z? Just Beyonce?

MEW: Yeah! Or like uh, maybe, like Andre 3000.

MR: That’d be rad! I bet he’d say yes.

MEW: Andre 3000 is a little in the territory of like… maaaaaaybe I could convince him (laughs). I feel like Beyonce’s a little unreasonable. Andre 3000 for whatever reason I don’t feel is unreasonable. That would just be…

MR: He’s a reasonable man. Look at his clothing. (MEW laughs in the background). We address longevity in artistic practice a lot at IAM (our publisher). What does longevity look like for you?

MEW: SPACEBOMB is built to be long-term. As an artist, your face is on the front of a record, you have a few albums, might have ten years, something like that, but people get tired of you after a while and you loose your fame and power. There is this other side of the music world focused on being a craftsman, being excellent at what you do. I try to be thankful for this every day. But I will be out of the spotlight. Not sure when, but whenever that light goes out, I’ll still be able work SPACEBOMB. That’s the goal. It’s about work ethic. I need to get better at writing and arranging. I need a deeper understanding of the music that I’ve taken in, and I need knowledge of music that I haven’t heard. There has to be a continuous push as an artist to struggle with your art. If not, you’re going to find yourself inactive at fifty. Visual artists do pretty good at succeeding late in life. Classical composers do pretty good, too. If you’re trying to keep your finger on pop culture for your whole life you can forget about it.

MR: Do you think it’s possible to rework pop music’s infrastructure?

MEW: Hip Hop has this amazing infrastructure: first you get in the game guest rapping on some records, then you have your debut, then you become a producer, and then you become an entrepreneur/businessman. There’s a graceful entrance and then exit out of the spotlight that rock n roll doesn’t really have.

MR: A reorientation has to occur, right? You have to ask yourself from the get-go what your bottom line is. You spoke of courage in your answer. From my perspective, a good dose of discernment and a whole lot of courage is absolutely necessary to work at an artistic practice, whatever it may be.

MEW: That’s really all it is. It is wisdom, courage, imagination, and work ethic. Those four things will get you a really, really, really long way.

MR: I’m glad we ended with this, because as a magazine, we believe that artistic excellence creates a pathway by which humanity can flourish.

MEW: If you’re able to be courageous about your decision-making, and particularly imaginative, that’s the golden ticket. And that’s not easy.

MR: I agree wholeheartedly. Is there any wisdom that you could pass off to people doing work like yours in other places?

MEW: When you can marry true vision with something you’re good at, it starts to become attractive to people. This record is the closest thing that I’ve made to myself. Like I said, I didn’t mean for this record to do anything, I mean nothing, I didn’t have any expectations for it and here I am talking to you on the phone (talking to like forty other people on the phone in the next few days). It’s crazy! It took me ten years to distill my knowledge, and my listening, and my stuff that I’ve been taking in through my personal life and professional life into a group of songs that I felt represented myself. Not only are they pure in that sense, but they are also married to ten years of work. Now I can bring a skill set and a self-awareness to the table. People want to see what humankind can kind of do despite the fact that things are broken. And there’s sort of a redemptive quality in watching that.

MR: Thank you so much! Your words are valuable to our community and we’re grateful that you took the time.

—–goodbyes——-

MR: He’s a good man!