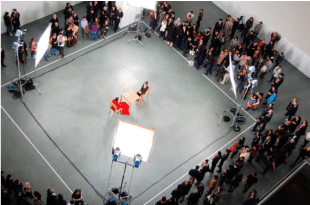

Perhaps you were lucky enough to see the show—before face masks and travel restrictions and crowd reductions and social distancing and quarantine and COVID-anything-at-all. If so, you were one of 750,000 who crowded into the Museum of Modern Art over the course of three months in the spring of 2010, to stand and stare at Marina Abramović and the museum visitor who was brave enough to sit across from the Serbian performance artist’s attentive gaze. 1,565 people participated in the Museum of Modern Art exhibit, some even spending the night on the sidewalk as they waited in line to warm the chair across from Abramović’s.

Abramović called her performance piece The Artist is Present, and she was—she literally sat in the same wooden chair for 7 and a half hours at a time, six days a week, without moving, speaking, eating or getting up to use the bathroom for three full months. That’s 736 days and 30 minutes in all, endured one painstaking second at a time. A square of white tape marked off the exhibit, and in that square was absolute silence and absolute presence.

(If you’re wondering, as I was, what she did when nature called, I can assure you that they planned for the eventuality. Abramović’s chair had a hollow core, in which she placed a plastic tub. She cut a hole in both her chair and her alternating red and white dresses—both designed specifically for this performance and both of which billowed around her ankles—to allow her to go about her business discreetly, while remaining on display for her audience. Then again, I found it surprising she managed to go at all, with all those eyes on her.)

Yet the wait to sit was a brutal affair, “a riot of the New York elite,” joked a friend of Sarah Deming, a New York City writer lucky enough to participate in the show. The Artist is Present required not only endurance of the artist herself, but also of anyone who wanted to occupy the place across from her—the jockeying for a quicker entrance, the ability to wait on a cement floor for hours without leaving the room, and the emotional resiliency to try another day if your chance never arrived. As Deming noted, “Marina’s work is very generous, but it has its razor edge.”

*

Most of Abramović’s performance art contrasts with her 2010 exhibition. Generally, the “grandmother of performance art,” as she calls herself, aims to shock, appall and disgust by submitting her body to a series of rigorous tests, seeking her own physical and psychological limitation as well as asking endurance of her audiences as they engage her suffering.

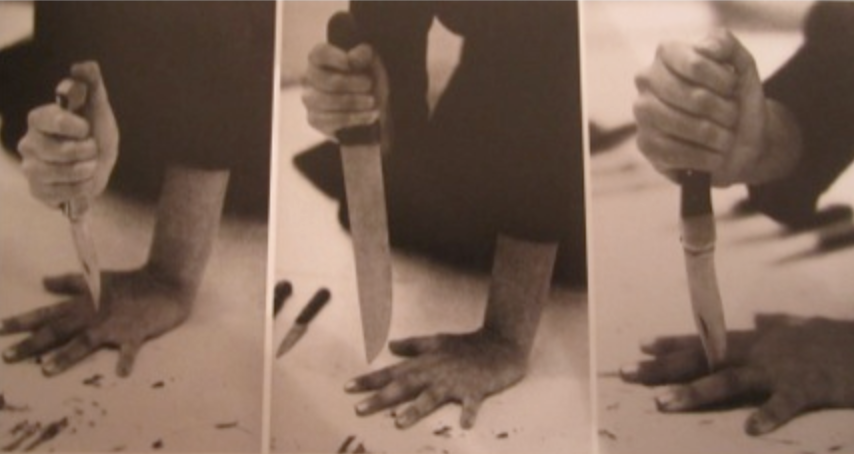

Her 1973-1974 Rhythm series, for example, exhibited herself as the canvas, pushing herself and her audience to engage her nude body in disturbing ways. In Rhythm 10, 1973, she recorded herself placing her palm on the table and, using twenty different knives, proceeded to play the Slavic knife game “five finger fillet” until she stabbed herself multiple times, a ritual marked in her own blood.

Likewise, her other works in the series—Rhythm 0, 5, 2 and 4—involved real pain, or at least the threat of it. In two of the works, the artist lost consciousness due to oxygen deprivation. In another, she swallowed pills usually prescribed for patients of catatonia and schizophrenia in front of an audience.

In the most disturbing piece, the artist assembled a table of props that included pliers, lipstick, a bullet and pistol, and invited her audience to use them on her body—the “object” of the work—at their whim while she stood impassive and silent, staring into the distance (Rhythm 0, 1974). By the end of six hours, her audience had stripped off her clothes, cut her neck with a razor blade, slathered lipstick on her skin, and, at the last, one audience member loaded the pistol, placed it in her left hand, and pointed it at her chest, at which time, the performance ended.

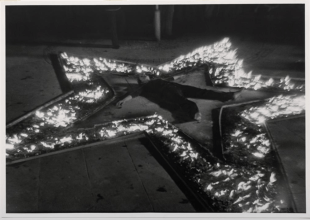

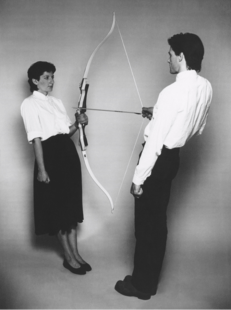

Her later work does similar violence to her body: she whips herself in front of an audience, carves a communist symbol into her skin, careens into a gallery wall so that it knocks her to the floor again and again. With the help of a close collaborator and romantic partner, Frank Uwe Laysiepen, called Ulay, she and he held opposite ends of a bow, an arrow tip aimed precariously at her heart (Rest Energy, 1980).

“Rhythm 0 and Rest Energy are two pieces, which for me was the most difficult in my entire life of [sic] performance artist, because in both pieces I was not in charge,” Abramović told MoMA. “In Rest Energy, we actually hold one arrow on the weight of our body and [sic] arrow is pointing in my heart. We have two small, little microphones on our hearts where we can hear the sounds of the heart beating. As our performance is progressing heart beats become more and more intense and it’s just four minutes and ten seconds, for me it was, I tell you, it was forever. So, it was really a performance about complete and total trust.”

*

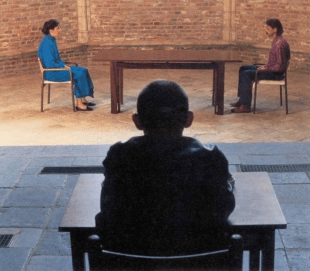

While her work with Ulay often illustrates violent clashes between the two, one of their collaborations anticipates the MoMA exhibit of 2010. In their series Nightsea Crossing, the two sit on opposite ends of a wooden table to stare at each other, their faces in profile for the audience as they remain silent and motionless for seven hours a day. They performed the piece 22 separate times between 1981 and 1987. During a performance—7-hour days of stillness—they maintained a silent fast, even during their off-hours.

Occasionally, they would invite another performer to join them, as in the case of the variation that included “the observer.” Swiss artist Remy Zaugg occupied a chair between the audience and Ulay and Abramović’s staring match, his back to the crowd, smoking a cigarette.

These performances invited the audience into the couple’s intimacy while also offering a commentary on the strained relationship between the watcher and the watched. One critic described the piece as centering on control itself, which also makes sense of Abramović’s violence: “Nightsea Crossing is about concentration and control over the body.”

Like Abramović and Ulay, other performance artists of the 1960s and 1970s turned to the body as their medium of choice, in part, to raise a middle finger to the gallerists eager to make a profit off of their works. To contemporary ears, a message condemning artistic commodification can feel trite and clichéd. Yet in the ‘80s, the themes of decommodifying fine art was confrontational, especially as many artists pointed their ire toward the institutional art world itself.

To dematerialize art made it harder to sell, to profit off of, to be trampled under the feet of a machine that cared nothing for the artists slaving in private to reach a climax of inspiration and mastery. Dematerializing art meant that artists could maintain their power, their control over their art and themselves.

For female artists, in particular, maintaining control over their art became one more expression of second-wave feminism. As Artsy writer Karen Chernick put it, “As a new wave of the feminist movement began to crest in the 1960s and ’70s, women artists turned to the then-uncharted field of performance. Adopting a new medium meant greater freedom to experiment, without fear of comparison to the generations of male artists that preceded them.”

Art made for oneself alone–not for a buyer or gallerist or even a viewer, not even constrained to a consumable medium–meant total independence.

*

It’s no surprise that Abramović’s art is controversial—hated by many, admired by a few, respected by thousands—except for the one piece, The Artist is Present, 2010. This piece was universally adored.

In fact, you can count up the moments of adoration, which were carefully chronicled by photographers and videographers whose endurance rivaled Abramović’s herself.

Take a moment like that of March 9, 2010. Abramović sits with her eyes shut and the guards lead over a man in a gray blazer who carefully sits in the chair directly opposite Abramović. Abramović lifts her head and opens her eyes, looking straight into his eyes. The man sighs. For a minute or two, they simply stare across the table at each other’s faces. Then the man’s eyes widen and his eyes grow glassy. Tears race down his cheeks, into his beard. He takes deep breaths and blinks rapidly, and Abramović’s eyes fill. This goes on for 17 minutes—the looking, the silent weeping, the stillness—before the man bows his head, shuts his eyes, stands, and walks out of the square, back into the anonymity of the crowd and the rush of New York.

Many of the 1,565 people who descended into the seat across from Abramović wept. We’re talking grown men and women, cynical New Yorkers, with noses running, eyes puffy, cheeks reddening—the kind of crying you might only do behind the closed door of a bathroom stall. A Tumblr account, “Marina Abramović Made Me Cry,” documented the overflow of emotion called. Participants broke down at the center of a crowd of spectators, all while Abramović, a few feet away, on the other side of a small table, and stared them down. Most people pay a therapist for the same attention.

*

In his observation of Nightsea Crossing, 1984, Remy Zaugg named what many of these participants felt Marina Abramović offered to them, and it was the reason they jostled each other to enter the performance: “Presence. Being present, over long stretches of time, until presence rises and falls, from material to immaterial, from form to formless, from instrumental to mental, from time to timeless.”

“It’s so simple, it’s like nothing there,” said Abramović in the retrospective documentary about her 2010 MoMA exhibition. “It’s just an artist sitting like a mountain. You know, I want to be just like a rock there, and looking you in the eyes…There’s just [my] pure presence…When [someone is] sitting in front of me, it’s not about me anymore because very soon, I’m just a mirror of their own self.”

*

Yet Abramović is now famous, and in an unavoidable irony of celebrity, presence recedes even as a person becomes well-known. Abramović hit platinum recognition (having received attention through both parody and commendation alike), and so she, herself, has receded from her art. That’s the only way I can make sense of her most current art experiments.

Recently, Abramović has turned her attention to the virtual. Filmed from every angle, she has created both mixed and virtual reality exhibitions. She has filmed herself pacing. She has acted on camera. And she has even been, strangely, swimming, in a head-scratching bit of climate activism. All these performances appear in front of viewers in an empty gallery, and in every digital iteration, the artist is absent IRL.

Her audience––that hum of bodies seated in the same place, in turns fidgeting and sneezing and leaning and sighing and crying––are reduced to anonymous viewers. They cannot meet the artist’s eyes. Nor can her audience meet the eyes of other viewers, who stand mere inches away in the same room, at least not without a clunky technology between them.

Abramović seems to be admitting that a body can only take you so far. What happens when your medium of choice ages? What happens when you grow ill, gray, gain weight, and hunch beneath the heft of time? What happens to performance art after its performer has passed?

Yet the production team behind the virtual works admit no such thing: as a spokesman said, “A hundred years beyond when anybody who ever knew [Marina] was alive, there will be people who will see her walk into the room and will feel that sense of connection, of human experience.”

I’m not so sure. If 2020’s “year of Zoom” has taught us anything, it’s that a body is irreplaceable, that screens cannot substitute presence, cannot come close to replicating a finger brushing a cheek with reverent care. The majesty of Abramović’s performances have always been the intimacy she offers to her audiences; without her, the art she’s known for is reduced to a pile of objects in an empty room.

As justification for this shift toward material or digital works, she has explained that her goal is a sort of artistic immortality. She has said, “I’m going to die one day—what do you do? The digital is one solution, and mixed reality is another.” For the performance artist, the body is the medium, and we all know the medium in which we pass our days is a fragile one.

Yet rather than turn toward a digital afterlife, I’d venture to suggest an alternative to Abramović: absence. Isn’t absence what makes presence so striking, so meaningful? Abramović can be certain that her art will continue to live within those who have experienced it in real time within their own fragile bodies. How could one ever forget the encounter with the master artist, eye to eye and face to face? Her body will mark them as they marked hers, will be remembered all their days until they, too, return to dust, forever changed.