From the moment I first encountered Bruce Herman’s work, I was at once invigorated and unsettled. The paintings nearly leap off the wall at you, with their bright colors and unusual yet wholly convincing blend of representation and abstraction. Herman is an American painter, educated at Boston University, who currently is the Lothlórien Distinguished Chair in the Fine Arts at Gordon College in Wenham, Massachusetts. His work has been shown around the world. Many of his paintings deal with religious topics and themes, but more broadly, they deal with the emotions, struggles, and quiet triumphs that people have faced since humans first appeared.

Recently, Herman released a book called “Magnificat”, which contains vivid reproductions of some of his recent work and some thoughtful essays centered around the life of the Virgin Mary, as well as the life stages of all women. The book accompanies Herman’s currently touring exhibition. Herman, as a Protestant, is perhaps an unlikely painter to consider Mary; however, Herman sees this work as embodying a “terrifying beauty” – a phrase borrowed from the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who is quoted on the book’s very first page:

“Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angelic orders? And even if one of them pressed me suddenly to his heart, I’d be consumed in his stronger existence. For beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror that we can barely endure, and we stand in awe of it because it coolly disdains to destroy us.

Every angel is terrifying.”

(From Duino Elegies)

I’m no art critic, but Bruce Herman’s work speaks volumes to me about the condition of humanity, and about the tension between terror and wondering joy. What I find so compelling in Herman’s work is his use of color and texture to communicate the vibrant perfection of the ordinary people whose stories make up history, as well as their flaws and imperfections.

Herman’s paintings, interestingly, remind me of my favorite theater in New York City is only a few blocks from where I live in Brooklyn. The Harvey Theater at the Brooklyn Academy of Music was originally a vaudeville theater, abandoned in 1968, then acquired and renovated in 1987 by BAM. The place is described as “creatively” renovated – though gilded and painted, there are places where the finish is made to look as if it has worn off, showing the bricks and plaster in spots and leaving it feeling a bit deconstructed, as if it is an theater which has seen and experienced the weight of the ages. Each time I see a production in this theater – whether it’s Macbeth, with Patrick Stewart, a Kronos Quartet concert, or most recently, Sam Mendes’ luminous production of The Cherry Orchard, I’m struck by the weight of history and humanity that this “imperfect” interior lends to the production. The imperfections remind me of the construction of the place, that the things people make – art or otherwise – are imperfect, because the creators of those things are a bit frayed around the edges.

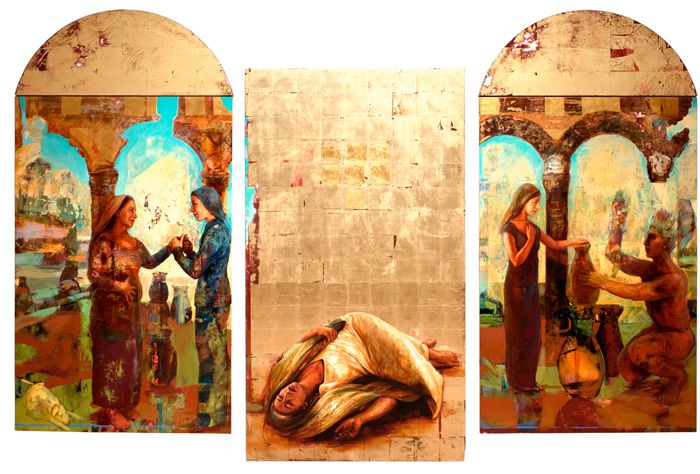

Herman’s work, to me, speaks to this same aesthetic. From a distance, the faces in Herman’s paintings seem to leap off the canvas – multidimensional and shot through with life. A closer look reveals an intriguingly deconstructed approach; colors one might not expect (green, blue) show up in the skin, and “imperfections” in tone, texture, and stroke are everywhere. The book reproduces Herman’s triptychs and portraits both in full and in detail, making it possible to see the technique.

It always seems as if there’s an extra layer underneath the surface of the painting that occasionally shows through – as if the paintings are painted over other paintings. In the center panel of a triptych called Miriam, Virgin Mother: Via Activa, Mary lies twisted and frightened on the ground, painted over a layer of solid gold leaf squares through which the faintest whisper of a Being can be seen. There is far more to this work than meets the eye.

It’s difficult to explain the effect of Herman’s work, but it belies a deep understanding of the tension between the beauty and joy of the physical world, and the complexity and pain that often undergirds it. Magnificat offers a glimpse into not only the story of Mary and Everywoman, but humanity and the beauty that can sometimes be found in imperfection.