What sort of man kisses a secretary at an office party and expects his wife to praise him for going no further? What sort of man quits an affair because it’s too much hassle? What sort of man begs his wife to deliver setup lines at cocktail parties to tee up his pre-planned punch lines? What sort of man attempts to declare moral bankruptcy to escape his obligations, pledging to be half the friend he was, half the husband, half the father?

A character in a Peter De Vries story, that’s who. The 20th-century New Yorker writer created a parade of shabby husbands and fathers who fail their families in hilarious fashion, offering a rich portrait of male vanity and insecurity. His heroes, almost to a man, are white-collar stiffs with jobs in Manhattan and comfortable homes in suburban Westport, Connecticut. Their concerns are the aggravations of timeworn marriages, the politics of dinner party invitations, and the quality of their highball cocktails. Borne aloft on the greatest rise of middle-class affluence the world had ever known, they eye each other’s wife and obsess over what college sweethearts think of them twenty years later.

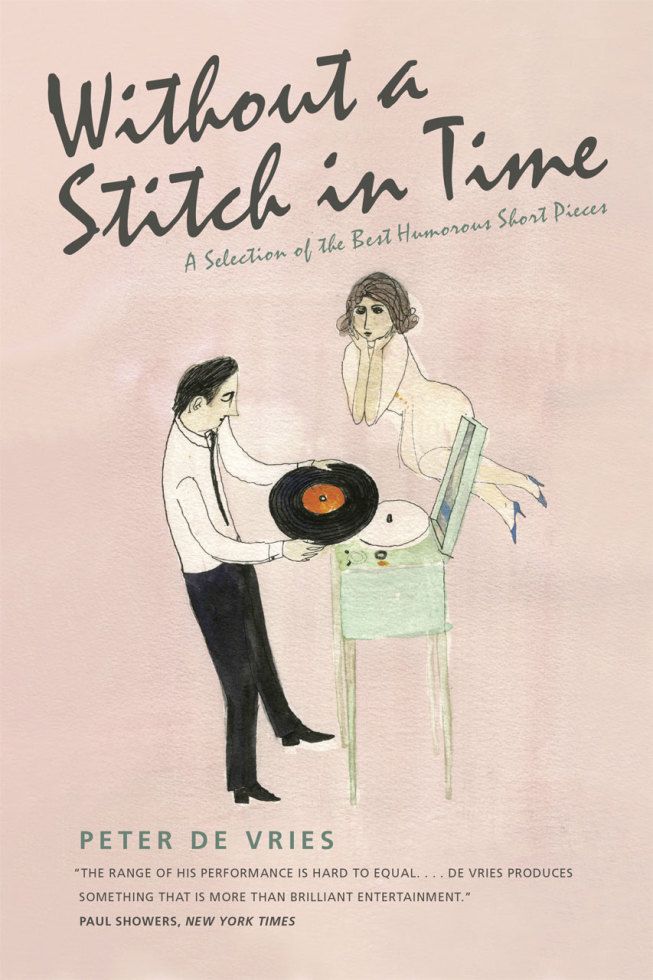

A trio of long out-of-print books, republished this fall by the University of Chicago Press, underscores the satirical brilliance of a mostly forgotten humorist. De Vries skewered a distinctly male form of idiocy, demonstrated by characters who are witty, well-spoken, and lacking what a later generation would call emotional intelligence. We get a slew of such heroes in Without a Stitch in Time, a collection of short stories reissued in November.

“When a man can no longer discharge his financial obligations, we let him off the hook,” says one character. “Why not when he can no longer meet his ethical ones? I have too many emotional creditors hounding me … Everybody keeps talking about moral bankruptcy, but nobody does anything about it. Well, I’m going to. I’m going to declare it.”

“In other words,” his companion says, “you want to tell your wife about us.”

“Nostalgia ain’t what it used to be.”

De Vries’s name has nearly vanished since his death in 1993, but for decades he was a mainstay of the East Coast literary establishment. He spent forty-three years as an editor at The New Yorker, contributing stories and assisting with cartoons. He published twenty-three books, to moderate commercial success. Proficient in one-liners, he coined phrases such as “Nostalgia ain’t what it used to be,” and “Deep down, he’s shallow.”

I’ve been mildly obsessed with De Vries, who shares my religious-ethnic roots in the Dutch Calvinists of Chicago. Born in 1910, he belonged to my grandparents’ generation, growing up among devout immigrant families who went to church twice on Sunday, forbade dancing and moviegoing, and cast a wary eye on the world beyond their South Side neighborhoods. In religious schools De Vries learned the doctrine of total depravity: our lives might be redeemed by grace, but they’re also marred by sin as pervasive as oxygen. For Calvinists, sinfulness includes more than specific lapses such as lying to your parents about skipping youth group for the pool hall. Total depravity means sin is a cancer that corrupts every cell of our God-created selves. Little wonder De Vries craved the levity of humor. He strained against the pieties of his family, mocking religion, especially the smug brand of Calvinists who believed their God had sorted the world into the elect and the damned—and they could discern who was who.

De Vries decamped from his working-class roots to the refined world of New York publishing, establishing a suburban commuter’s life in Westport presumably much like those of his characters. That Mad Men setting of martini lunches, commuter trains and the giddy newness of suburbia provided the most fertile ground for his satire. Several of his best novels explore that territory or launch from it, including Tunnel of Love (reissued this year), The Cat’s Pajamas & Witch’s Milk (1968), and the dark masterpiece The Blood of the Lamb (1961, republished in 2005).

There’s no doubt his work has aged unevenly. Reading De Vries requires a certain patience for wordplay, and later novels rely too much on farcical gags. Some of the parodies gathered up in the anthology Without a Stitch in Time are aimed at long-outdated targets. But that book, which draws mostly on his New Yorker stories, also contains some of De Vries’s finest stories. Those deserve a closer look.

In “The Flesh and the Devil,” we meet one prototypical schlub at the boozy end of an office Christmas party. Frisbie finds himself with an empty stomach and a friendly temp secretary. They leave together for a bar, after which she invites him to her apartment. He kisses her, remembers his wife and excuses himself. He congratulates himself, thinking of all his colleagues who might not have showed such marital loyalty: “The more he thought of it the more gratifying his conduct seemed, and, presently, the more his satisfaction struck him as worth sharing with his wife, not for the light the incident put him in but as a certification of their bond.”

Not surprisingly, his wife reacts differently than he expects.

“Where?” she asks. “Where didn’t you sleep with her.”

Frisbie stumbles forward like a man “having stepped out on a high wire on which going ahead might be difficult but turning around impossible.”

“You’re not looking at this thing right,” he protests.

Such emotional cluelessness surfaces throughout the collection. De Vries’s men are fluent in Freudian psychology and deeply analytical about their own lives. About their partners, they are considerably less perceptive.

De Vries’s women are rarely fully drawn characters—one of his chief limitations as a writer. But they are often capable sparring partners who expose their partners’ blind spots. In “A Crying Need,” a film critic for a community newspaper brings dates to watch screenings with him. One girl takes him to task for his pretentious criticism: “You could be too clever for your own good, you know. Your stuff is brilliant…but I wonder if life can always be lived on that plane.”

That’s a bit of self-criticism from De Vries, whose pun-loving mind was always running out ahead of him. He can’t seem to resist a well-turned quip. At times that serves him well, such as in “Compulsion,” about a compulsive punner whose incessant wordplay drives away companions. But some of the weaker pieces in Without a Stitch seem to be stories in service of a punch line, rather than the other way around.

When his humor works, though, it works. In “The Last of the Bluenoses,” the narrator whines that his dreams have not kept pace with the sexual revolution. While the broader culture flings off Victorian mores in favor of miniskirts and free-love credos, he complains that the orchestrator of his dreams provides nothing more risqué than a bare ankle: “Ankles! Can’t he get his mind on higher things?”

One of the things I appreciate most about these stories is the way they show how humor is a double-edged sword. It can cut through trivial cocktail-party banter to reveal the heart of things, like the jester who’s the only person in the medieval court allowed to mock the pompous king. But it can also be a weapon a speaker wields to keep others away, forming a protective distance of irony. De Vries grasps both possibilities.

The punner in “Compulsion” visits a therapist who tells him, “You are fundamentally afraid of people. This habit of yours was a way of mutilating conversation…you do so in order to escape the risks of engaging in it on an adult level.”

The characters in Without a Stitch begin to run together, which is sort of the point. The stories function as a cycle about the anxieties of the middle-class man at mid-century. Over and over, they invent crises: starting affairs, confessing to non-affairs, picking fights with dinner-party rivals. One adolescent sweating over his girlfriend’s possible pregnancy delivers a line that could be the book’s theme: “We pay for security with boredom, for adventure with bother.”

I found myself wondering which is the core problem for these men, anxiety or boredom? Or if it’s both, which causes the other?

That got me thinking about what’s missing from these stories. Except for showing up at their nondescript office jobs, these characters have few obligations beyond themselves. They have wives and children but seem to take them for granted. They don’t seem to be from the bedroom community of Westport, but they don’t seem to have roots elsewhere, or obligations to extended families or aging parents. (I say “seem” a lot because these brief stories leave much unstated.) With few exceptions, these men are not involved in churches, civic groups, PTAs, little-league coaching or other roles that weave a person into the fabric of community. One man is told by a doctor that he needs a hobby other than pouring himself highballs. He buys a model airplane and tries to fly it in his yard, a decidedly individualistic activity.

Lurking beneath these humorous flights is a void these characters do their best to ignore. It goes unspoken, but it shows up in their vanities and their all-too-relatable attempts to be the smartest person in his room. If life is nothing more than a popularity contest, you’d better be damned sure you’re popular.

The narrator in “The Irony of It All” chokes down a cocktail as the host of a party, a novelist he can’t stand, reads a maudlin passage from his latest project. At an especially bad line, the man says, “A snicker escaped me at the same time that a sob caught in my throat.”

De Vries adds a hiccup to the man’s troubles and plays the scene for laughs. But the snicker and the sob—rising up together—encapsulate his characters’ condition. They snicker so they do not sob. For his characters, success seems to roll in on the breeze, fickle and arbitrary. But failure arises from something broken deep inside them. De Vries rejected the religion of his youth, but he never shook the Calvinist understanding that our best efforts still bend toward brokenness. That sense of total depravity stayed with him. It appeared in the guise of humor, and it charged his light-hearted stories with surprising depth.