Love is a strange thing.

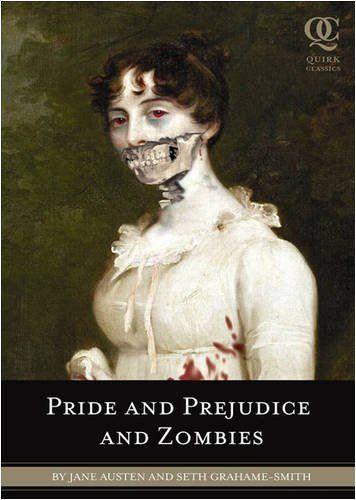

Yet stranger, still, are the things that cause us to fall in love. For some, flirtation begins with arrogance – a haughty tango between the mind’s sharp wit and the heart’s fragile emotion. This quickly turns into verbal sparring, more often than not in public, and with so much inflated pride now at work, it is difficult, indeed, to know whether it is affection or affront which is the binding tie, if there is any bond at all. Such is the familiar tale of Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy, the two protagonists of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies.

That’s right. And zombies.

In a daring, yet happily successful undertaking, Seth Grahame-Smith has taken Jane Austen’s celebrated classic Pride and Prejudice and expanded it to include an absurd subplot of a strange English plague which has turned those afflicted into “unmentionables” – more commonly known as zombies. While keeping the whole of Austen’s novel in tact, complete with social commentary, irony, and masterful literary technique, Grahame-Smith takes a few liberties (to say the least) with the characters and their circumstances.

Take a look at Elizabeth Bennet, for example. She retains her overdeveloped pride and uses it as often as in the original to reject marriage proposals and propriety, but she also has another reason for doing so: she is one of the world’s finest zombie slayers. Having studied in China under the direction of Master Pei Liu of Shaolin, she has not only her own pride at stake, but her honor and duty to her master and country as well, all of which take priority over settling down with a husband or behaving the least bit ladylike. As a warrior, Elizabeth is, perhaps, even more an example of feminine independence and strength than she ever was in the original, and it remains this soldierly distinction that most catches the eye of Mr. Darcy. Yet a notable difference between this version and the classic is that because Darcy, too, is a warrior, we actually have a binding tie between the couple, and one that had never been so objective and discernable in Austen’s original.

Then there is Lady Catherine de Bourgh, benefactor to Mr. Collins and aunt to Mr. Darcy. True, her distaste for Elizabeth is still the result of class distinction, but what prevents Lady Catherine from acknowledging Elizabeth as an even remotely capable zombie slayer is that she trained in China instead of Japan. (Lady Catherine is so partial to the ways of Kyoto that she has her own host of ninjas who, in one of the finest additions to the story, are methodically [and graphically] dispatched by the obstinate Miss Bennet.) In keeping with her original character yet putting the focus on the fight against the zombie plague, Lady Catherine refuses to give credit where it is in fact due, and the more Elizabeth proves her skill, the less inclined Lady Catherine is to hold her in any esteem at all.

Perhaps the most entertaining of character deviations is the change made to Charlotte Lucas just before her marriage to Mr. Collins. In an unexpected twist, Charlotte is bitten by an unmentionable and must accept that in due time, she will become one of the stricken. Though it goes against her training, Elizabeth agrees not to kill Charlotte until she has transformed completely, leaving her to marry Mr. Collins whose perpetual oblivion prevents him from recognizing Charlotte’s impending zombification, setting up such comedy as in the following dinner scene:

…Elizabeth’s eye was continually drawn to Charlotte, who hovered over her plate, using a spoon to shovel goose meat and gravy in the general direction of her mouth, with limited success. As she did, one of the sores beneath her eye burst, sending a trickle of bloody pus down her cheek and into her mouth. Apparently, she found the added flavor agreeable, for it only increased the frequency of her spoonfuls. Elizabeth, however, could not help but vomit ever so slightly into her handkerchief.

Mind you, we’re only scratching the surface here. There are zombie attacks on balls, dinner parties, traveling carriages, even one on Darcy’s Pemberley estate. And every time, either Elizabeth or Darcy is there to swing a Katana sword, fire a pistol, or in the most delicious cases, just start throwing punches. There are multiple mentions of Elizabeth “disregarding modesty” with high kicks to zombie skulls (and in one case, Mr. Darcy’s) and where male bonding is concerned, there is no better activity than an organized zombie hunt, the unmentionables lured into the open by heads of cauliflower placed in fields. (Zombies, apparently, mistake the vegetable for stray human brains.) There are even some violent additions to Wickham’s story and a unique alteration to the plot that prevents Jane and Bingley from marriage. All of this without losing a sentence of Austen’s original tone.

And that is perhaps the most refreshing, yet surprising thing about Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. Despite the expansion, it remains solid literature. Granted, there is some innocence lost and much absurdity added, but because Grahame-Smith intended to be as serious as he did ridiculous, all of the additions are written in Austen-esque English, compromising neither style nor structure in the novel’s delivery.

This also means, for those of us who feel a bit guilty when reading any sort of “fluff,” that the book functions as one of the few zombie stories we can read without having to justify it to our literarily critical acquaintances. And while it can never replace the original in high school or college English classes, it will undoubtedly be more appealing to teenage boys who must otherwise be threatened with month-long prohibitions of internet access in order to pick up any novel associated with an academic requirement.

Much as the characters in the original Pride and Prejudice cannot be taken too seriously – indeed, that is their common downfall in the first place – Pride and Prejudice and Zombies ought to be taken with an equal grain of salt. To take some of the most eccentric characters in classic English fiction and give them something even more ridiculous than themselves to dabble in cannot be construed as an honest attempt to achieve weighty or sincere literature. It can, however, be seen as a light-hearted way to revive and reconnect with a work which, though it will never die, may grow stale from time to time.

While there will forever be critics who disagree, there is very much a place for such well-constructed literary blasphemy as Grahame-Smith has committed and we all might benefit from thus opening our minds to the carnage and hilarity delivered herein. That is, unless you’re the sort of person who prefers eating brains to embracing their more conventional uses. But then I like to think that even zombies have something akin to a sense of humor.