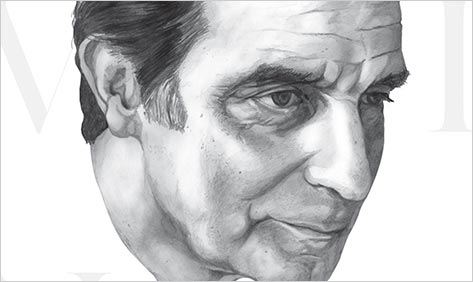

To commemorate Italo Calvino’s upcoming birthday, we’re rerunning this piece.

To many contemporary college students and used bookstore aficionados, the work of Cuban-born Italian author Italo Calvino is a gateway drug into the world of experimental writing, the kind of name you can drop confidently to underclassmen to secure your perceived status in the avant-garde of the well-read. Students in poststructuralism courses who can slog (or love) their way through If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler might sample only slightly less heady pleasures later on between the pages of The Castle of Crossed Destinies or The Barron in the Trees, and pick up indie girlfriends for sure by reading passages aloud from Invisible Cities. In the scholarly sphere, Calvino’s name is now fixed beside that of Umberto Eco in as an icon of effective continental, experimental writing in the 20th century, and the recent publication of his letters by the Princeton University Press is sparking retrospective reviews from all of the major papers and periodicals, many of which are the written equivalent of a head-scratch and a shrug.

Calvino’s letters are athletically written and often industry-focused: He spent the better part of his career as the manager of a publishing house, and those who invest in the big volume will be in for much more genial shop-talk then lyrical prose, extemporaneous criticism or infant fiction. This may register to many as a disappointment. Reviewers who approached the Letters hoping for short fictive experiments like those of the wonderful and absurd Cosmicomics, or perhaps more likely, a personal narrative that corresponds to the young protagonist’s political adventures in The Path to the Spiders’ Nests, found them dry and impersonal. The Guardian’s Ian Thompson was more optimistic than most, cautiously observing that “Above all, the letters illuminate the politics of book publishing in Italy after the overthrow of Mussolini.” In other words, they are letters about Other People’s Books (also the title of a collection of Calvino’s writings published in Italy), and about the trouble of publishing them in a partisan European country that is recovering from Fascism and a lost war. Very often, what we encounter in the letters are Calvino’s opinions about other Italian authors – a pretty far cry from the kind of personal disclosures that could rock the scholarly world. But even these observations are studded with insights, like those in this brief comment about Luigi Pirandello, the prestigious Italian dramatist of a generation before:

Pirandello is hard, I’ve read him again and again, and reflected on him, though I’ve not yet properly digested him…But however much I continue to discover some new plus points in him, I can’t quite reduce the distance that separates us. Dentone too says he’s seen him but adds: philosophy is not poetry and does not supply us with dreams.

Here Calvino aligns himself with the poets, and in that loyalty we catch a glimpse of his orientation as an author; one who later observes that “…perhaps only the liveliness and mobility of the intelligence escape…the dense net of private and public constrictions that enfolds us.” And to intelligence we might easily add “imagination,” which Calvino possessed in spades.

And here is precisely where his critics zero in on him. Jonathan Galassi of The New York Review of Books notes the apparent “dryness” of the letters as deeply contrasting with the whimsical twists of his fiction, and from there launches into a guarded bit of diminution:

The depicting of the actual was never Calvino’s forte. Even in his first, most realistic novel, inspired by his partisan experience, the young hero undergoes rites of passage perhaps more proper to the realm of the fairy tale. Fantasy allowed him a kind of detachment, a freedom from self that he aspired to in writing, and “a burst of energy, action, optimism…which contemporary reality does not inspire in me.” He rejected as “decadent” “autobiography, introspection, egocentrism, all things that I have always hated and fought against.”

To criticize Calvino for failing to “depict the actual” is not a casual observation: It aims straight for the heart of his literary project, which was thoroughly invested in the actual tragedies and hardships of wartime and post-war Italy and Europe, no matter how obliquely his letters reveal that concern.

As a test case, his famous short story collection Invisible Cities is as good as any at revealing the undertow of the actual beneath Calvino’s fantasies. Framed as a series of exchanges between Marco Polo and his Tartar commissioner Kublai Khan, the subject of which is ostensibly Polo’s impressions of the various cities in Khan’s vast empire, the narrative of Invisible Cities quickly veers into the conceptual, remaining effervescently beautiful even while it undermines the credibility of Polo’s stories. “Your cities do not exist,” Khan tells Polo at one point. “Perhaps they have never existed;” to which Polo replies, “While, at a sign from you, sire, the unique and final city raises its stainless walls, I am collecting the ashes of the other possible cities that vanish to make room for it…” Later, Polo confesses to Khan that all of the dozens of cities he describes might, in fact, just be different versions of his native Venice, which (and here the poststructuralist students gasp collectively) he may never have left at all, making the whole collection nothing but a dream.

Certainly, these tropes and concepts seem far removed from the mundanity of the editing room, the trenches of WWII or the political dilemmas of a post-Fascist Italy, but in the stories themselves, and their meditation on the human project as summed up in the city, we can find a critical mind at work that has read clean through the library and brings the whole weight of that erudite intelligence to bear against society’s flaws. In his fifth story under the heading “Cities and Signs,” Calvino’s Polo tells Khan,

No one, wise, Kublai, knows better than you that the city must never be confused with the words that describe it. And yet between the one and the other there is a connection. If I describe to you Olivia, a city rich in products and profits, I can indicate prosperity only by speaking of filigree palaces with fringed cushions on the seats by the mullioned window…But from these words you realize at once how Olivia is shrouded in a cloud of soot and grease that sticks to the houses, that in the brawling streets, the shifting trailers crush pedestrians against the walls.

Here, waxing theoretical, Calvino observes astutely how words can often suggest their unstated opposites. But under the flag of that linguistic observation is another, bitterly practical one, about how prosperity tends to generate poverty at its fringes, or even at its heart. The piece brings to mind stories of Italy before WWII, where a single glisteningly-dressed Fascist battalion would get ferried from town to town ahead of the touring Mussolini, so that each impoverished community would appear both armed and prosperous: A gilded surface that belied the actual state of the “brawling streets.”

It is true that Calvino chose to write his fiction at a certain theoretical distance and that he specialized in the fantastic. But like the filmmaker Guillermo del Toro after him, whose monsters in Pan’s Labyrinth are physical signifiers of the warped Republican officers of the Spanish Civil War, some of whom seem to derive sexual pleasure from torture, Calvino has used the fantastic in fiction to process historical human violence, but without diminishing the monstrousness of that violence. His fantasies are not escapes from reality, but lurid analogues to it. In The Baron in the Trees, the fatal promise of one boy to live his whole life without touching the ground has luminous narrative consequences (how do you court a woman from the treetops?), but we are never allowed to forget that at the heart of his oath is a giant vote-of-no-confidence for humanity; a misanthropic streak that decays his fantasy-life in the leaves, and which was probably the reaction to a stuffy, loveless aristocratic childhood:

There is humor in these reflections, certainly, but a bitter humor that only solidifies our sense that this narrator cannot help but inherit the coldness of the family he has fled. Read sensitively, The Baron in the Trees turns out to be a caustic domestic drama dressed up as a fanciful concept novel, and in Calvino one finds this commitment to wrestling with real personal or historical issues informing even his most far-fetched storytelling. Very often, Calvino’s covert subject is human industry, and its apparently inevitable decline into oppression and war; and though Invisible Cities is his sly historical commentary par excellence, the personality revealed in the letters is no less dedicated to these concerns.

In one of them, Calvino writes that:

“My working method has more often than not involved the subtraction of weight. I have tried to remove weight, sometimes from people, sometimes from heavenly bodies, sometimes from cities; above all I have tried to remove weight from the structure of stories and from language.”

The chain of priorities he describes here, which ascends from the practical into the conceptual, suggests not only that he tended to begin his composition with an observation of the streets or a morning with the newspaper, but that he even thought of language — which for him was a realm of dangerous abstraction — as connected at the roots with people, and with cities, and with the “heavenly bodies” that might ultimately hold both people and cities accountable for their tendency to embrace corruption. The man we encounter in his recently published correspondences might strike us as either fanciful or austere, but we can begin to know him best by learning how he wanted his work in fiction to “subtract weight,” or in other words, to relieve human burdens. This is not the mission of a fantasist, but of an author who believes he can freshen our experience of the mundane, or even the dire, by presenting it to us in fantastic new shapes. Far from having trouble depicting the actual, Calvino specialized in its transformation and interpretation: His work lifts us into places where the surreal always seems familiar, so that we can return to a reality where, as he said of his own experience during the two years when he was compiling his book of Italian Folktales, “…everything that happened was a…metamorphosis;” the magic here was in the stories, but the transformation was in the reader.