The notions of nature are lonely photographs.

Think about it for a moment. How does one go about describing nature?

Where does one begin? What does one include?

Perhaps more importantly, where does one end their portrayal?

For instance, I may say that I find few images of nature more beautiful than the silent, meditative impressions of a snowy field backstopped by a stark black wood.

Pause again, slowly reading the previous line.

I find few images of nature more beautiful than the silent, meditative impressions of a snowy field backstopped by a stark black wood.

Hmm.

You may be sitting there thinking, “Yes, I understand, I know exactly the scene he describes. I saw just a similar scene this morning while driving to work.”

or

You may feel something like this: “Ok, what are these ‘silent, meditative impressions’ and how does snow convey them? Also, how black is this wood? Is this just a poetic term for a fence on the edge of a field, or is he indeed speaking of a very dark forest? The Black Forest perhaps? Germany?”

Quickly it becomes apparent that the reader is no longer engaging with nature vicariously through the writer’s description, but is instead trying to find meaning through the chosen words, carried along by streams of consciousness.

The experience has morphed into an understanding of semantics rather than substance.

At once the reader is confronted with one of the obstacles and beauties of nature writing: it is impossible to recreate in your mind the scene as described by the writer. Only the writer knows the image he describes.

Take for instance another line describing this indisputably snowy landscape.

The subdued blankness of the snow contrasts with the harsh void of the forest, forming a scene that sings of elegiac serenity amidst its bleakness.

Apart from the creeping thought that perhaps Cormac McCarthy has abandoned violence for simpler pursuits such as wax poetic nature writing, one still runs into the barrier of language in the search for full understanding of the image described.

Put simply, this winter scene is a snapshot, a photograph captured by my eyes and left to develop in the recesses of my conscious, sitting and waiting till a kindred sentiment appears to save it from loneliness. Put even simpler, I saw this image of snow, a field and trees last week while driving home. It cannot be completely understood by anyone but myself, as it waits warm and alone inside my head.

As I said, the notions of nature are lonely photographs.

——–

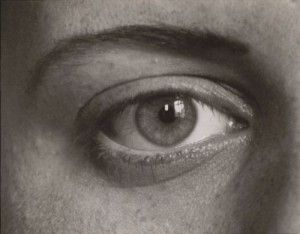

In his 1927 remarks on a photography exhibition at the Cologne Art Union, German photographer August Sander stated that photography “can render things with magnificent beauty but also with terrifying truthfulness; and it can also be extraordinarily deceptive.”

He continued, “There is nothing I hate more than sugar-glazed photography with gimmicks, poses and fancy effects. Therefore let me honestly tell the truth about our age and people.”

August Sander spoke regarding his work People of the Twentieth Century: A Cultural History in Photographs, a collection of forty-five portfolios of photographs of German society during the post-WWI Weimar Republic.

Sander sought to portray German life as it was, photographing what he called “archetypes,” documenting through photography slices of the German citizenry. As such, his collections bore titles as The Farmer or The Artists.

By objectively presenting the German people as they were, Sander included the handicapped, vagabonds, androgynous women, and Communists in his work, not just standard, traditionally imagined faces of moderate, mainstream Germans.

Purely, August Sander wanted to tell the truth.

——–

This is not a meditation on snow. This is not a lesson on the history of German photography. This is not even a case for the aesthetics of nature, which, let us agree, is of the highest value.

This is a question of truth in reality, of accepting beauty in this world as it is. The contrasts of the white snow and black forest harkened back to the black/white of August Sander’s photographs, a thread of connectivity stretching decades.

Does a specter of a snowy field hold as much truth as the images of August Sander? Yes, but it is an aesthetic hybrid of truth, trapped as it is within myself, understood only by me and locked in its time just as the objects of Sander’s camera were trapped within theirs.

Maybe there are times to simply accept the truth of life as it is, not as it ought to be. Perhaps these imperfect images are the truest signposts of a world to come, indications of the need for rebirth. But until that time, let us not ignore the beauty in the brokenness. Let August Sander find pride in his people. Let me find solace in a lonely snowy field. Let that image lie dormant in my mind, reminding me of a past photographer’s attempt to find truth.

Winter always seems to instill a desire for things to come, but for that passing moment, riding in my friend’s Subaru Forester, all I wanted was that field surrounded by a dark wood, and the truth it hid.