It was in 1918 that Lev Kuleshov—film theorist, father of the Soviet Montage school of cinema, director of The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924), political partisan, teacher—ventured a hypothesis. The hypothesis: the dramatic effect of a film was found not in the content of its shots but rather in the edits that join them together.

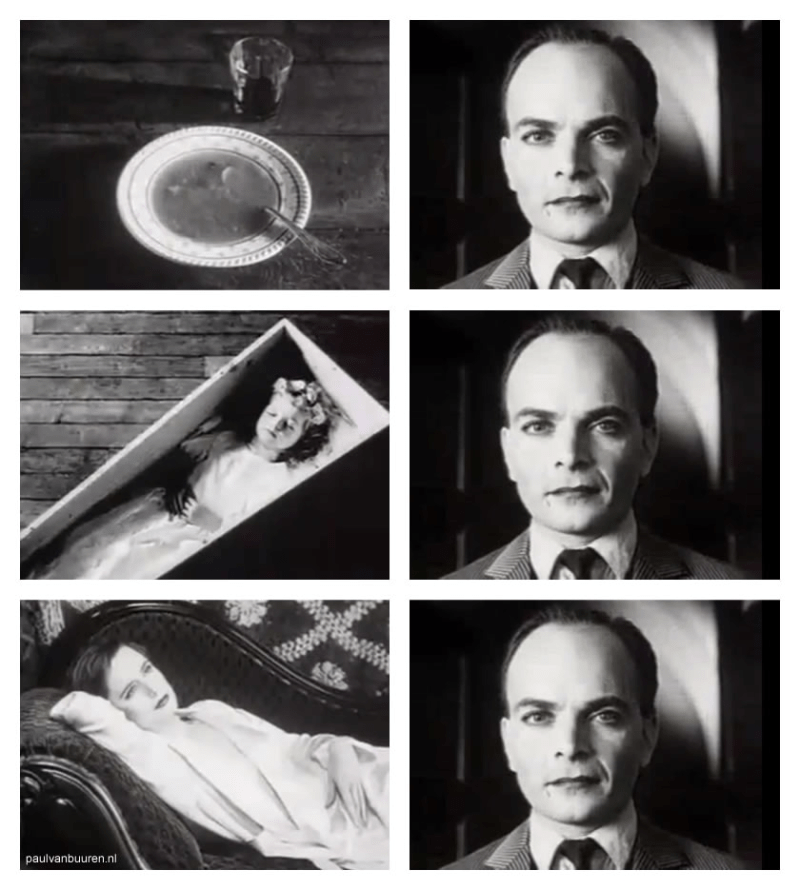

Kuleshov put his hypothesis to the test. Taking an expressionless long shot of the actor Ivan Mozzhukhin peering into the camera—presumably, because footage of the original experiment has been lost— he broke it into three parts. Then he intercut each practically-identical segment with three other shots—a bowl of steaming soup, an attractive young woman, and a child lying dead in a coffin. When he showed the segments to audiences and polled their reactions, they swore that Mozzhukhin’s expression had changed from piece to piece. When staring at the soup, Mozzhukhin was hungry; at the young woman, lustful; at the child, mournful.

“The discovery stunned me,” Kuleshov wrote, “so convinced was I of the enormous power of montage.”

The Power of Montage

And his amazement was catching. Soviet greats of the silent era, such as Vsevelod Pudovkin, Aleksandr Dovzhenko, Dziga Vertov, and Sergei M. Eisenstein, were likewise stunned. It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that the Soviet silent era, its “golden era,” was the flowering of a shared fascination with Kuleshov’s discovery.

Kuleshov experimented further. In Art of the Cinema, Kuleshov’s first book, he tells of several other tests, including the creation of a single woman from a hodgepodge of different women. He writes, “By montage alone we were able to depict the girl, just as in nature, because we shot the lips of one woman, the legs of another, the back of a third, and the eyes of a fourth.” It was “a totally new person.” And even though she was a composite, according to Kuleshov, she retained “the complete reality of the material.”

Kuleshov tended to exaggerate the implications of these constructs: “it was not important how the shots were taken, but how these shots were assembled.” Alfred Hitchcock, decades apart and worlds away, called it “pure cinema,” when the montage gives rise to meanings that exist nowhere to the eye, but only in the mind. This interplay between montage, perception, and meaning has come to be known as the “Kuleshov Effect.”

What Kuleshov actually discovered and what he thought he discovered are not necessarily one and the same. How successful would the Mozzhukhin experiment have been had he not appeared “neutral” but enraged, elated, or better yet, jogging in place? These montage composites are limited by plausibility (a woman has lips, legs, a back, and eyes) and the content of the shots themselves (neutral stares versus, say, directed actions, like, ‘appear as if you are frightened’).

Yet Kuleshov was right to emphasize the power that editing has over motion pictures, even to the point of bending the inner “reality” of shots. What stunned Kuleshov was the incredible flexibility of the medium, and, with that in mind, the power it granted him to provide moving pictures with new contextual meanings. Such authority over meaning strikes us as obvious today, but at the time the “photographic” image was held to be a totally faithful, “concrete,” inviolably “true” artifact, free of the shortcomings of subjectivity. This turned out to be false; or, rather, true in a limited sense. What Kuleshov was witnessing was the dissolution of a paradigm—which no doubt felt like the melting away of the thing itself.

Thinking about Film

Film historian Ronald Levaco called Kuleshov the “first aesthetic theorist of cinema,” a deserved appellation. Yet it’s an oddity of Soviet film that such a theorist, doing strange experiments in an editing room, could have so great of an effect. Indeed, without the total destruction of Russian cinema by a chain of sweeping social disasters—World War I, the October Revolution, the Civil War, Bolshevik rule, and the mass starvation of (conservative estimate) 5 million people—it would have been impossible. The Civil War devastated Russia’s cultural centers, and studio owners fled the Bolsheviks with their cameras and film stock in tow. The instruments of film, incredibly expensive, difficult to operate, and very hard to replace, were gone. “Moscow had 143 theatres operating before World War I,” historian Peter Kenez recounts, “but in the autumn of 1921 not a single one remained in operation.”

In 1920, Kuleshov joined Moscow’s All-Union Institute of Cinematography, established in 1919, as an instructor. The Institute was the world’s first film school—a film school without film stock. While Hollywood, during this time, was making film, the Soviets and Kuleshov were thinking about film; and thus developed a thickly theoretical and experimental approach to filmmaking, as was readily apparent as soon as film equipment became available to them. (One wonders, incidentally, what kind of cinema Hollywood would have made had it at least once been destroyed.)

Films without Film

Kuleshov’s workshops are legendary. Known as the Kuleshov Group, Pudovkin was one of his students; Eisenstein studied under him for three months, but was inspired—“influenced” is a better word—by Kuleshov for a lifetime; sometimes as a rival; later as a dear friend.

Kuleshov would direct his students in mock shoots of “films without film,” drilling them over and over again through a series of taxing acting exercises. He would position the actors before empty cameras and they would act out the scenario, pretending that their performances were being recorded, in preparation for the time when the Soviet Union once again had film.

Re-Centering Cinema

Meanwhile, Kuleshov continued his editing experiments—having no film with which to shoot did not mean there was no film with which to play. Using whatever films they could get their hands on—films left behind from the days of Tsar Nicholas II, foreign films allowed entrance into Soviet territory under Lenin’s New Economic Policy, and others which circulated illegally throughout the Soviet Union—Kuleshov and his cohort would break them down and reassemble them in a variety of configurations. They were especially captivated by the innovative (and supremely racist) films of D.W. Griffith, the American director behind The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance. Kuleshov studied Intolerance obsessively; swapping its parts; changing its order; and re-constituting its meaning and themes (a task made easier by its silence). Like a cinematic Doctor Frankenstein, Kuleshov poked and prodded; re-arranged and re-animated; then did it all again. Breakdown then re-assemble; breakdown then re-assemble. It was this breathless experimentalism that yielded the Kuleshov Effect.

Kuleshov became convinced of the vaporousness of the shot and, naturally, of the inconsequence of the director as a cinematographer. In such a psychological setting, the center of Soviet film shifted from the camera to the editing table; from “production” to “post-production.” From there it unleashed its “golden age.” For all of its deformities—or because of them—Soviet montage remains one of the truly lasting and perpetually fascinating movements in film.

The Hammer, the Sickle, and the Editing Table

So what of Kuleshov the filmmaker? The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924), his most famous film, was a financial success and one of the first feature length films in the Soviet Union. It’s a key point in cinema history, but not a great work of art. His best film was Po Zakonu (1926), based on a short story by Jack London; it’s very good, but, again, not great. The students of his cinematics—Pudovkin, Dovzhenko, Vertov, and especially Eisenstein—made far more compelling things of his theories and principles than he ever did. Yet his theories are implied in almost every aspect of their work. This makes him a minor filmmaker but a major figure in the history of film.

Soviet Montage had a short-lived but high glory, lasting from 1924 to 1930, brought to an end by the artistic exhaustion of the theory, squabbles among the movement’s major figures, the rise of sound, and the disapproval of Stalin. Eisenstein, the greatest and most natural filmmaker of the group, explored both the roots and frontiers of Kuleshov’s doctrine—“the content of the shots in itself is not so important as is the joining of two shots of different content and the method of their connection and their alteration”—at once realizing its greatest triumphs while stretching it far beyond the sinews of plausibility. Strike! (1925) and The Battleship Potemkin (1925) are undoubtedly two of the greatest and most unique—because stylistically unrepeatable—films ever made. Eisenstein both fulfilled and exhausted Soviet Montage.

By 1930, the “Golden Age” which Kuleshov fathered came to an end. Soviet Montage had marched across the globe, deposited its greatest cinematic achievements, theories, and inventions into the tool chest of—something called—“global cinema” (a prestige genre cooked up by Hollywood and its California-based film schools), and was spent.

Back in the Soviet Union, Stalin and his party apparatchiks turned against the movement; and the names of its practitioners, especially Eisenstein’s, became bywords among political aspirants, encapsulating all that is wrong with its misguided adherents, decadent artists lost in sterile theory, too effete to portray the strengths and vigors appropriate to “the people’s” cinema.

It was in 1935, though, that Soviet Montage officially died. Under the motto “For a Great Cinema Art,” on January 8 through 13, Stalin convened the All-Union Creative Conference of Cinematographic Workers, with Stalin himself present on the final day to distribute awards for cinematic achievement. Stalin orchestrated the proceedings to denigrate Soviet Montage and to elevate Socialist Realism in its stead as the single aesthetic of “Great Cinema Art.”

For five days, Kuleshov’s theories were officially disavowed, but Eisenstein, who had become most popularly associated with the movement, was the named target. Director Leonid Trauberg criticized Eisenstein (and through him the movement) for making “stupid poetry”; director Sergei Yutkevich read aloud a letter from George Sand to Flaubert—which accused Flaubert of too much intellectual study—and pointed its finger at Eisenstein: “You are a fool who roots around in his straw and eats his gold.” Even Dovzhenko, the coward, himself a Soviet montage filmmaker, feeling the heat, took a turn: “If I knew as much as he does I would literally die.” He then threatened Eisenstein, whose lack of production—he had not completed a film in six years—noticeably displeased Stalin: “If you fail to make a film within twelve months at the latest, I beg you never to make one at all. We will have no need of it and neither will you.”

Only one man, during these five tense days, came to Eisenstein’s defense: his mentor, rival, and friend, Kuleshov. “You have talked about him here with very warm, tearful smiles as if he were a corpse which you are burying ahead of time.” Kuleshov slapped back: “I must say to him, to one who is very much alive, and to one whom I love and value greatly: Dear Sergei Mikhailovich, no one ever bursts from too much knowledge but from too much envy.” Then he took his leave: “That is all I have to say.”

Kuleshov defended the man who explored his theories the most ingeniously and made them known to the world—but the movement he had founded was dead.

In the late 1920s, several years prior to Eisenstein’s public flaying, Kuleshov had found himself, like Eisenstein, the object of intense scrutiny and renunciation by party wannabes. Four of his adoring students, one of whom was Pudovkin, came to his defense:

Some of us who had worked in the Kuleshov Group are regarded as having “outstripped” our teacher. It is a shallow observation…

We make films—Kuleshov made cinematography.