The sky above Stonehenge was two-tone with a bizarre, crinkled texture. Sharp slivers of grey flowed in curves and wisps and disappeared into the eggshell-colored background. The taupe rocks below were flecked with red and steel blue — the same odd texture as the sky. Colors stood in strong contrast next to one another as in a Van Gogh painting. But something about them hinted this was not a painting at all.

A bold red flame extended off the top left corner of the canvas and broke out into the open air. It billowed from the tail of the Millennium Falcon (yes, from Star Wars) as it careened toward the ancient stone structure. A glance at the tag revealed the mystery of the medium, if not the message: “duct tape.”

I punched the piece’s five-digit code into my phone and tapped to register my vote. As I turned to leave I caught a glimpse of buildings and a passing car reflected in the copper colored window of the Auto Fixit Body Shop where the piece was hanging. Was this experience part of the artwork, I wondered. Did the artist want me to read the modern city behind me into its strange collision of the past and imagination cast in duct tape? Why the Auto Fixit Body Shop? Did it matter that both the venue and medium were not intended for making, but for repairing? As I wandered away looking for the next piece to contemplate, I realized I could come to my own conclusions, but I couldn’t ever really be certain.

This feeling of uncertainty is, for me, the best part of my yearly visit to ArtPrize. Now in its fifth year, ArtPrize is an independently organized festival-meets-competition in Grand Rapids, Michigan. This year featured over 1,500 artists from 47 different countries with attendees casting almost half a million total votes. ArtPrize looks like what might happen if you combined an art fair and a contemporary art museum, shook them up, and poured them out over three square miles in the center of a city. Art might be anywhere: in the river, on the tops of buildings, hanging from the ceilings of restaurants, on the sidewalks, and, of course, on the sides of auto body shops.

As you wander through the environment created by ArtPrize it is hard to distinguish the art from the non-art. More than once I have seen passersby come upon a sculpture or installation and, unable to decide what it is and whether it is in the competition, say, “Is this…something?” Sometimes you squint and look for a tag, sometimes you try to overhear an explanation, sometimes you wait and see, and sometimes it is impossible to tell whether “this” particular thing is “something” or not.

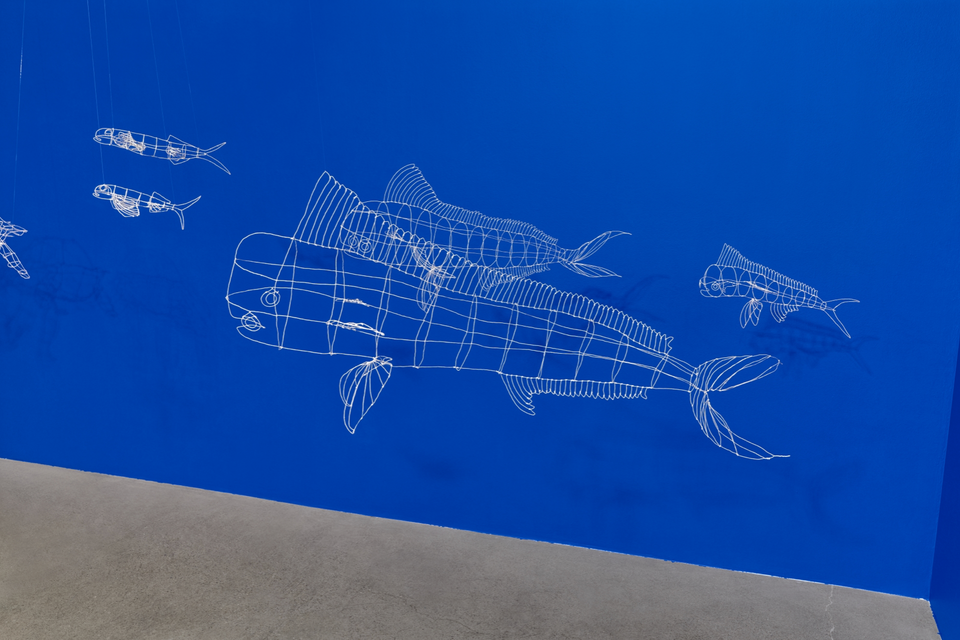

Uncertainty can be disorienting, but it also affords certain freedoms. Visitors to ArtPrize feel no pressure to like what they see. Any artist over the age of eighteen with a venue willing to display their work can exhibit at ArtPrize, so it isn’t uncommon to find trite pieces next to revelatory ones, cheesy ones next to exquisite ones. Some of the art is charming, if strange, like the wooden fish carving I saw displayed inside a plastic dome that looked like an enormous eye protruding from the wall. Some of the art is profound like the 3-D model of a river at night created using digital models of sound signatures captured all over the city. When you go to ArtPrize you can expect to see art that is zanier than at any other art competition, but you might also be surprised—maybe even embarrassed—at what strikes a chord inside of you and makes you feel something you haven’t felt looking at art before.

When you look beyond the highly visible hype-focused pieces like this year’s giant mechanical fire-breathing dragon, which occupied one restaurant’s parking lot, you see that ArtPrize has developed a value for craft and technique that is sometimes missing in the highly conceptual corners of the art world. Previous winners of the $200,000+ publicly chosen grand prize have included a grand-scale photorealist painting of a wave, two elaborately detailed pencil drawings, a meticulously rendered 13-foot-high stained glass mosaic of the Crucifixion, and this year’s winner, a 20-foot-wide finely wrought quilted image of a Michigan shoreline. Of course, none of these pieces broke new ground in terms of content, but each was a large-scale display of masterful artistic technique.

Why hasn’t something like ArtPrize existed before? It would be hard to imagine ArtPrize without the GPS and mobile technology that lends coherence to the otherwise absurd idea of scattering thousands of works across the center of a city. Each piece of art is geotagged and as soon as a visitor enters the three-square-mile ArtPrize zone, they can register on the ArtPrize app, find routes, venues and works, as well as vote without ever speaking with a guide or buying a ticket.

As the novelist and coiner of the term “cyberspace,” William Gibson, recently said:

Cyberspace, not so long ago, was a specific elsewhere, one we visited periodically, peering into it from the familiar physical world. Now cyberspace has everted. Turned itself inside out. Colonized the physical.

ArtPrize has taken this concept and turned the art world inside out — putting virtual ballots into the hands of each and every visitor. Rather than allowing art to exist in the specific “elsewheres” we call museums and galleries, ArtPrize takes it to the streets, to the bars, to the coffeeshops and to the conversations of regular people. ArtPrize is a radically impure environment, unlike the hospital-white walls of museums. It is like a theater in which the footlights that distinguish the actors from the audience have been turned off. Suddenly the production, promotion and purchasing of art no longer feels like a specialist enterprise reserved for a select few — it’s now the stuff of everyday life.

Eventually ArtPrize goes away. The footlights come on again. Most of the artists remove their works and return home. Like the law of nature that makes oil mixed in water separate again, art leaves the sidewalks and the auto body shops and returns to the museums and galleries. But some of the residues of ArtPrize remain. The permanent pieces like mosaics, sculptures and murals fill in new bits of the city’s white space each year like a paint-by-number project. I hope someday a time comes when it is impossible to tell when ArtPrize ends and begins. But until then ArtPrize teaches us to pay attention. It keeps us asking, “What is this? Is this…something?” And it leads us to approach our world with a healthy dose of uncertainty.