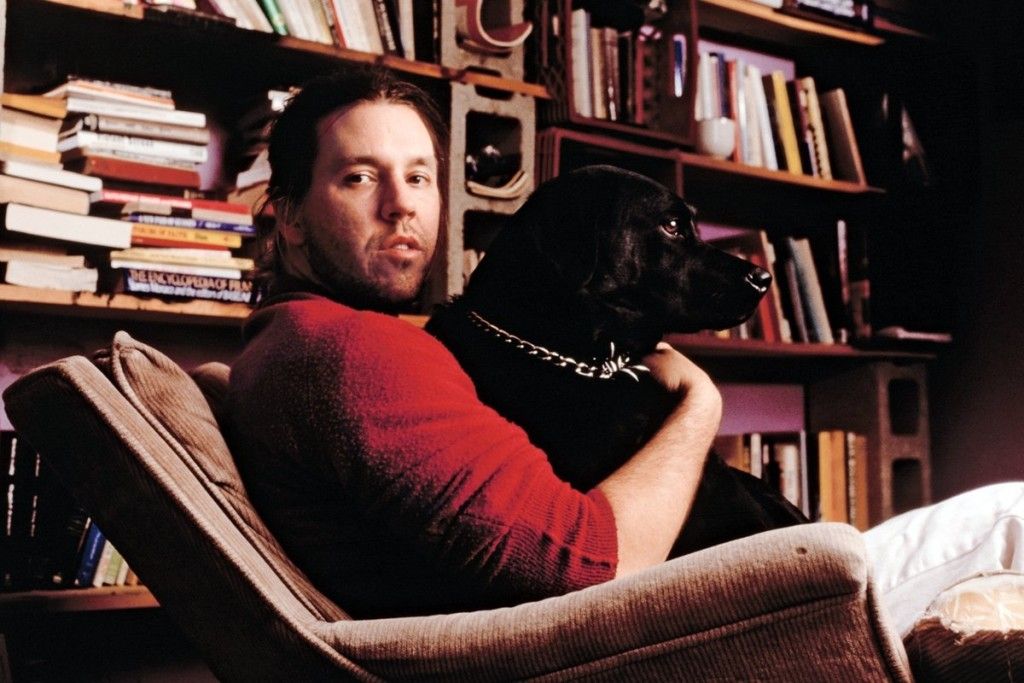

In the introduction to Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, a transcript of a five-day-long interview with late writer David Foster Wallace, David Lipsky describes his book as “the one way of writing about him that I don’t think David would have hated.” This is a remarkable claim, given Wallace’s own apprehension about the very same interview. “If you wanted,” says Wallace (in both the film and the book), “you’re gonna be able to shape this essentially how you want. And that to me is extremely disturbing. Because I want to be able to try and shape and manage the impression of me that’s coming across.” Wallace’s desire to curate his own image is a familiar one to many of us, a desire compounded today by the proliferation of social media personas and tampered images. Interpretation is a risky and dirty business. It is this confusion of what people truly are and hope to be, before others and before themselves, that James Ponsoldt’s film adaptation of Lipsky’s transcript, The End of the Tour, gets exactly right. What many of us clumsily refer to as the problem of interpretation, and which is known in academia as hermeneutics, Wallace gracefully and soberly understands as loneliness.

It bears mentioning that David Foster Wallace’s relatives have publicly voiced their opposition to the film. And the onscreen interpretation of Wallace by actor and comedian Jason Segel is no small irony, given Wallace’s own prolific writing on, and self-admitted addiction to, television and film. The movie, to it’s credit, does not shy away from this dynamic, and takes pains to portray Wallace’s obsession with television: Segel’s Wallace watches the dénouement of Broken Arrow with slack-jawed, panting attention, and guiltily admits to Jessie Eisenberg’s Lipsky that he can’t keep a TV in his house, because it would be on all the time. It’s little touches like these that give the film the true-to-life veneer of a biopic, while masking the reality that viewers are actually watching an interpretive journey that has already been mediated once through Lipsky’s book. But these new interpretive layers have caught many viewers off guard, and the discontinuities can be frustrating at first.

For instance, in Slate, Forrest Wickman meticulously demonstrates the un-truth of Wallace’s “church dance” at the end of the film. According to Wickman, the image of Wallace dancing in church, while beautiful and therapeutic in the context of the narrative the film presents, may have been only as real as the lie Wallace was known to tell reporters.

“[Wallace] often told journalists he was going to church as cover for his attendance at recovery meetings, to stave off a relapse into drug and alcohol addiction. And if the brief vision of Wallace dancing is meant to be taken non-literally, as a moment of him finally achieving freedom from his own self-consciousness, it’s quite untrue to the rest of the movie—which is very much about how David Foster Wallace was a terribly sad, lonely person who could never truly escape his own head.

The scene “rings false” as, in Wickman’s words, the film is “fooled by its own subject.” And Wickman sets the record straight in short order, with a flurry of anecdotes, quotations, and other evidences of the real Wallace’s purported inability to enjoy the fictional moment presented in the film. In Wickman’s view, it’s false of the film to portray Wallace in this way, and demonstrates a kind of exploitative, directorial stupidity.

Wickman has fallen for the film’s biopic sheen, and is evaluating the film’s success or failure based on what he assumes to be the responsibilities of biographical art. There are two notable characteristics of a perspective like Wickman’s. Firstly, there is a moral obligation, both to the subject and the audience, to get the story exactly right, and it is the subject itself that becomes the judge of accuracy (and this becomes even more complex when the subject committed suicide seven years ago). Secondly, when an interpretation “fails” based on the standards we have just discussed, it is morally or artistically at fault?

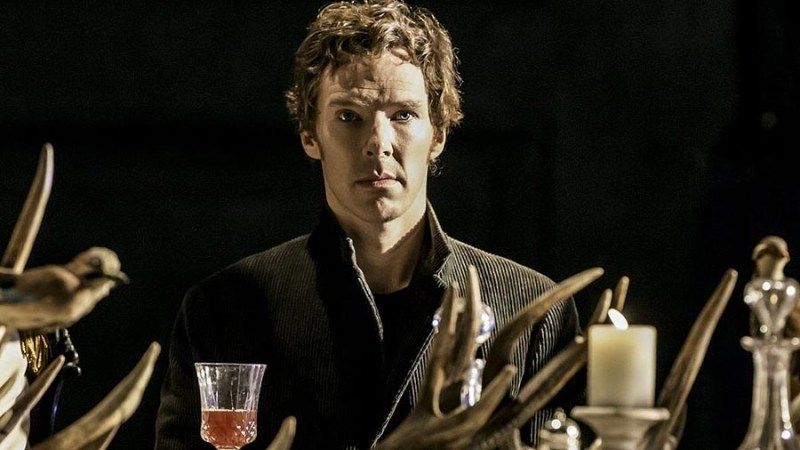

Another recent example of this fraught relationship is Benedict Cumberbatch’s Hamlet, which opened at the Barbican in London this month. The production quickly reneged on its decision to open the play with the famous “to be, or not to be” soliloquy due to public backlash; a New York Times critic opined, “You’re bringing out your big showbiz number at the beginning and it’s hard to take seriously after that.” Again, we have the same attitude at play: there’s something exploitative, “showbiz-y,” in reorganizing Hamlet, or in depicting David Foster Wallace at a church dance. The masterpiece and the master ought to be left alone, we are told, to speak for themselves, to decide for themselves what they want to and should in fact be. But the obvious problem is that they can’t. Each individual performance of Hamlet is, by nature, an interpretation. There is no primordial Hamlet that we can return to. Shakespeare himself does not decide what Hamlet is. The performers and the director now perform this duty, attempting to offer something new to the discussion, to pour new wine into new wineskins. Likewise, every word penned by David Foster Wallace, after his death (and if we’re honest, even before), becomes an opportunity for something different and expansive.

The End of the Tour is a movie about loneliness and fame, about how we craft our image and appreciate (or detest) the images of others. Interpretation can be a lonely act, as individuals are isolated in their own heads, with nothing but their personal judgments and concerns. In the film, Lipsky and Wallace both appear in the role of the self-conscious critic, with their deep insecurities, their fear of being misunderstood, misinterpreted, or simply “made a fool” of, to use Wickman’s verbiage. Each man dreads the interpretive power of the other: “I don’t mind appearing in Rolling Stone,” Wallace tells Lipsky, “but I don’t want to appear in Rolling Stone as somebody who wants to be in Rolling Stone.” At another point in the film, Wallace believes that he has reached an understanding of Lipsky’s simmering jealousy and admiration, and tries to call him out: “I don’t think you want be to me.” Lipsky replies just a little too quickly, “I don’t.” This is interpretive judo. Both men are feinting, watching their footwork, and occasionally opening themselves up to strike, cautious not to reveal their next move, or their next weakness. Neither one truly grasps the other’s character; a truth that Wallace seems to poignantly understand. This heightened individualism is at play in the critical voices that have attended Cumberbatch’s Hamlet and Ponsoldt’s End of the Tour. The critical impulse, while not always misguided, is a lonely one.

Wallace spent a lot of time thinking about this problem. In his conversations with Lipsky, he offers this insight:

“There’s a certain set of magical stuff that fiction can do for us. […] One of them has to do with the sense of… capturing what the world feels like to us, in the sort of way that I think that a reader can tell ‘Another sensibility like mine exists.’ Something else feels this way to someone else. So that the reader feels less lonely.

Wallace believed that fiction could identify the reader’s own observations and insecurities, offering company for an otherwise lonely mind. It is at this point that The End of the Tour finds hope. At the end of the film, Lipsky offers up his own interpretation of Wallace at a reading of Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, following Wallace’s death. The camera hovers at Lipsky’s shoulder as he reads to a room of sober-faced bookies.

“When I think of this trip, I see David and me in the front seat of the car. It’s nighttime. It smells like chewing tobacco, soda, and smoke. […] The wheels are making their slightly sleepy sound of tape being stripped cleanly and endlessly off a long wall. On the other hand, we seem not to be moving at all, and the conversation is the best one I’ve ever had.

Lipsky tellingly begins, “when I think of this trip,” placing himself, the interpreting subject, in the role of storyteller. The interpretive community responds attentively, hanging on to Lipsky’s every word. It is in this context that the film cuts to Wallace’s ecstatic dance. After the writer’s life closes, his books are reopened, his words remembered, and new interpretive worlds open up. It is now possible for us to imagine Wallace dancing in church.

Artists—directors, musicians, writers—need this interpretive space, and we need to relinquish our modernistic notions of truth to give it to them. While we don’t want to delude ourselves with false hopes and images, we also should not live in fear of the interpretive nature of our lives and worlds. The reality of interpretation, especially the interpretive power of fiction, was a great hope to Wallace throughout his own life-long struggle with loneliness. “We all suffer alone in the real world,” Wallace said in a 1993 interview with Larry McCaffery, “True empathy’s impossible. But if a piece of fiction can allow us imaginatively to identify with a character’s pain, we might then also more easily conceive of others identifying with our own. This is nourishing, redemptive; we become less alone inside.” [2] If Wallace is right, the problem of interpretation is inaccurately labeled. Rather than a problem to be addressed, interpretation is the inescapable and life-giving reality of our common experience as human beings. While this reality can be, as Wallace noted, “extremely disturbing,” it is also deeply natural, and good. In light of this reality, The End of the Tour is best understood as an interpretive retelling of five days of David Foster Wallace’s life. Whether the film succeeds as an interpretation will be the topic of much future discussion, but we should be careful if we expect it to succeed as anything else.

Citations1. David Lipsky, Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip With David Foster Wallace (New York, NY: Broadway Books, 2010).