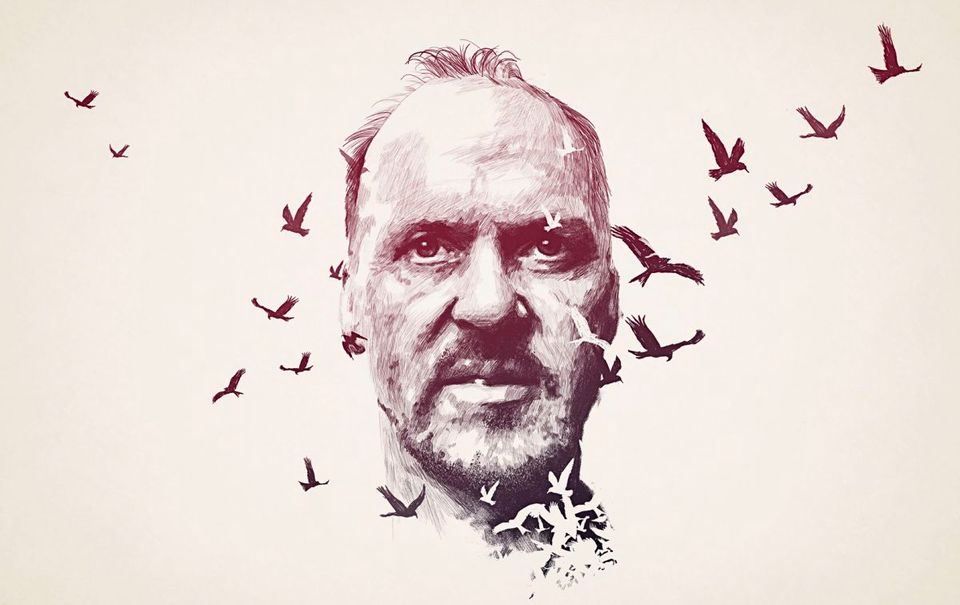

Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman is a glorious and often mesmerizing blend of realism and illusion. Like its character Sam Thomson (Emma Stone), the film is a “beautiful mess.” Winding through the labyrinthine bowels of a Broadway theatre and spilling out onto the streets of New York City, each scene blends into and out of the next. The film’s cinematography (i.e. long takes that seamlessly flow into even longer takes) creates the visual expectation of realism – immediate and direct facticity. The camera catches each bit of action just before it’s gone, but it also captures plenty of events that aren’t really there, a range of illusions that only Riggan Thomson (Michael Keaton) and the audience see and hear. Much like the supernatural elements of 2010’s Biutiful, the illusions are there, but they not the point.

So why this wild conglomeration of reality and fantasy? For starters, it makes for the filmmaker’s most adventurous and entertaining film to date. More importantly perhaps, like all of Iñárritu’s other films, Birdman is meant to re-educate us in the dramatic interplay between the presence and absence, love and loss, fear and hope we experience in our own lives. This black comedy reconnects us to the elegiac spirit embodied by Raymond Carver’s poem “Late Fragment,” which opens the film:

And did you get what

you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

beloved on the earth.

The breaks from realism in the film are numerous and diverse, some subtle and others overt. We barely notice the ways that the film abbreviates time and space as one scene flows into another. The clues are there but not easily spotted. For instance, consider a scene between Riggan and his onstage co-star Mike Shiner (Edward Norton). Shiner’s profile appears in the New York Times and Riggan receives the paper. Moments later, he confronts Shiner about specific details found in the story, without any apparent time passing and therefore no time to actually read the article. Perhaps more obviously, later in the film Sam tries to comfort her deflated father with news that video of his embarrassing scramble through Times Square in his underwear garnered 350,000 hits within the first hour, but we know that the fiasco took place only minutes prior to their conversation. With respect to the shortening of space, we find out on the morning of the play’s opening that Riggan’s drunken ramble a few doors down from the bar near his theatre was in fact many, many blocks away and necessitated a mid-morning flight as Birdman back to Broadway. This cinematic prestidigitation helps to smooth out the story, but perhaps it signals something more.

The grand illusions of the film – Riggan’s levitation, violent fits of telekinesis, and flying – are wonderfully fun interruptions to the dry comedy. But as much as they delight they also disturb. We learn that there are no witnesses to these feats other than the film’s audience. If Riggan possesses these powers, they are simply part of the furniture inside his own strained internal life. While the audience must carry with them this troubling realization, we are eventually met with a more direct confrontation. Whether as a result of his mounting stress and anxiety or simply by accident, Riggan’s id finally and climatically gives birth to the full manifestation of the Birdman. What we had only experienced as the dark and brooding presence of an inner voice we now behold in all his “comic book to silver screen” glory. The Birdman lives. And he has a message for us. Eyeing the camera with maniacal fury and machismo, the Birdman erupts with a startlingly soliloquy. He proceeds to tell us exactly who we appear to be: weak and impatient, hungry for the debased violence of so many Hollywood blockbusters. He wants to shame us into accepting our tasteless lust for spectacle and feed it: “Look at these people. Look at their eyes. They’re all sparkling. They love this…” The Birdman’s momentary break through the film’s fourth wall doesn’t last long, but it does serve to unsettle us with its shocking revelation of what Riggan is facing in his desperate and solitary struggle. Such a break heightens our concern for the main character and elevates the tension and pity we feel. Will the illusion take him over? The audience can now fear the Birdman as Riggan does.

While the studio calls the film a ‘black comedy,’ that label barely begins to describe the tragedy embedded in the humor of it. By far the most tongue-in-cheek offering from Iñárritu, this film still carries within it all the pathos that his other films 21 Grams and Babel embody with unrelenting poignancy. Iñárritu’s singular strength is conveying raw human emotions in both an unsettling and deeply intimate way.

The authentic emotions put forward through his characters pierce us more than help us. The catharsis they provide proves arresting and leaves us more stunned than soothed. Recall 2003’s 21 Grams and the bitter defiance of Cristina Peck (Naomi Watts) at her father’s suggestion that she will inevitably “move on” following the sudden and tragic deaths of her husband and daughters. That film orbits around the sheer inability to heal from such a trauma. Iñárritu’s characters reveal to us their profound woundedness but allow us no easy resolutions for their hurting. Such encounters prompt an awareness of our own woundedness and emotional frailty. Rather than dispelling such concerns or distracting us from our own pain, Iñárritu’s films heighten our sensitivities, and like 2006’s Babel with its tale of emotional confusion and isolation, they provide extended meditations on essential human dilemmas. Birdman participates in the same kind of energy, and for that reason, it cannot be taken or left as mere black comedy.

When Riggan confides in his ex-wife just before his fatal final scene that he “was never present to his own life, and now…doesn’t have it anymore,” we finally come up against the most honest and painful moment of the film – a quiet and unhurried moment attended only by the emotional telekinesis of one human confessing to another. Such moments ground Iñárritu’s films and ensure that the magic of his illusions stand apart from so much frivolity and spectacle in movies today. The illusion of this film is one we desperately need to cling to because it is the magic of one soul finding another.

This tender confession and the scene that follows, a scene that finds Riggan onstage with a gun to his head, are not the final word from Iñárritu. We are left perplexed by the hospital room scene at the close of the film. The blissfully reassuring tones of Riggan’s reunion with his ex-wife and daughter are matched only by his restored status to unprecedented celebrity. In this case, it is in fact too good to be true. This is the scene of a funeral and not some grand comedic dénouement. The film’s realism finally and fatally collapses into complete fantasy. Whatever continuity existed in the story has been irreparably ruptured. Evidence of this rupture can be found in a few key places. First, following Riggan’s suicide on the stage, the camera departs from long takes and begins a series of sharp, sequential cuts. After a short parade of sublime imagery (jellyfish on the beach at sunrise, dust particles caught in the light streaming through Riggan’s dressing room) we are ushered to Riggan’s bedside. This shift in cinematography alerts us to an altogether distinct filmic territory. Second, and most dramatically, Sam finally witnesses her father’s powers as she stares out the window. She sees him flying and not falling to his death.

So, what should we make of this final scene? Is this Riggan’s last thought before death? Is it a projection of his imagination’s deepest wish and hence proof of his complete break from reality? We don’t know, but we certainly did enjoy watching it. Undeniably, it’s the ending audiences want. Whether this last trick constitutes Iñárritu’s boldest polemic against Hollywood or not, the funerary conclusion to the film makes one last plea to its audience. It leaves us with a newfound urgency to reestablish connection with others – to make our relationships more real and secure and not live solely in the fantasy space of our own insecurities and fears. Love, it reminds us, is the impossible magic we must force ourselves to believe.