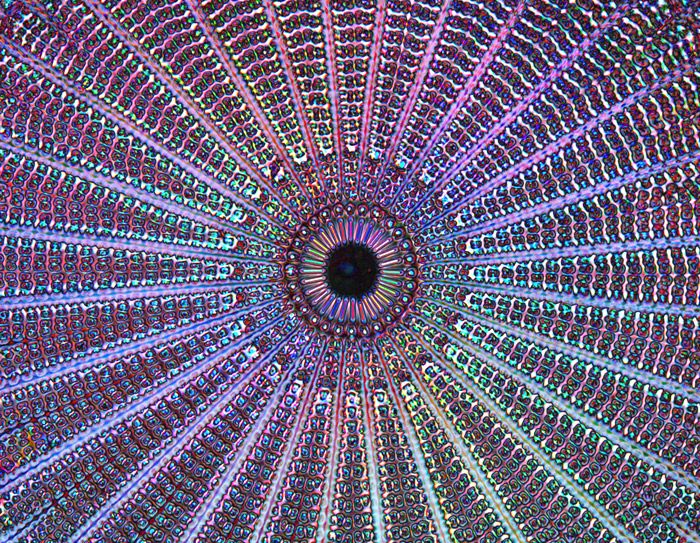

“The scaling down is unlimited. Like the tiny diatom shells whose markings, however magnified, change almost indefinitely into new patterns, so each particle of matter, ever smaller and smaller, under the physicist’s analysis tends to reduce itself into something yet more finely granulated. And at each new step in this progressive approach to the infinitely small the whole configuration of the world is for a moment blurred and then renewed.

~ Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

This is the only nightmare I’ve ever had: when I close my eyes the room recedes on all sides, giving way to a dark, sickening expanse. Blackness impinges everywhere on my field of vision, but it is not empty, not blank. Often I feel a need to complete some task immediately—a need to have already done the impossible that combines the sense of limitless space with a feeling of slipping time, the moment for action continually present but continually already past, like a parabola approaching its limit, closer each moment but never arriving.

Sometimes someone’s life is on the line and I am on the verge of acting, but already certain that it is too late. Sometimes I am in the presence of God, and the time is past to mend what I would like to mend as I rise, slowly, suspended by my chest, toward the unknown.

This dream, if it is a dream, combines gut-dropping nausea at infinity with panic at the sudden realization of time passing. But there’s something else too: an overwhelming intricacy, a sense of ineluctable complexity. I’ve never known what to make of it, what I could possibly infer from it about the shape of my mind. But occasionally in waking life, a sharp, sinking feeling of deja vu offers me hints, if not to meaning, at least to some pattern of associations.

***

The economist Eric Beinhocker estimates that the number of products available in advanced economies is in excess of 10 to the 10th power, two orders of magnitude greater than the presumed number of species on the planet.

Of the species on earth, over 10,000 may be represented within a spoonful of garden soil, potentially amounting to a million individual fungi and 10 billion bacteria, not to mention protists, nematodes, and larger creatures like earthworms and insects. We are treading on worlds within worlds, each square inch teaming with the drama of life and death.

In our own bodies, the cells of our human organism are outnumbered 10 to 1 by the cells of microscopic creatures sharing our abundant ambulatory biosphere. Look at a person, see an ecosystem.

Around us and inside us matter flows, boils, swings, grows and proliferates, in motions so complex that no constituent part can be predicted. From the steam above a coffee cup to the price of rice in China, the world is full of systems so teeming, so ungraspable, that the imprecise but evocative term “chaos” remains the most compelling name for the theory that describes them.

***

The infinite scalability Teilhard de Chardin saw in diatom shells complicates the already difficult question, “How long is the border of Tajikistan?” The answer: infinite. Or, it depends on the size of your measuring stick.

Imagine flipping a yardstick end over end around the mountainous nation, its boundaries set by tortuous soviet gerrymandering. You would arrive at one figure. But someone flipping a stick half that length would find a longer border by taking in more complexity, including more of the bends and curves of the real geography. And someone with an even shorter stick would find a longer boundary still, ad infinitum.

***

On the frontier between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, a fox flitted just beyond our sight. We ran a circle around the hill, my hunting companion and I, gum boots sloshing through the snow. Each time we charged down a valley then crept up the crest of the next one, it would disappear beyond us down the next ridge. We ran breathing cold, ragged breath until we finally glimpsed a few seconds of fleeting red. We pulled up, fired and missed.

Down below us came shots from the rest of the party. The fox ran over yet another ridge. Borders snaked around us. One moment the quarry was in one nation, the next moment the other. Kyrgyz, Tajik, Tajik, Kyrgyz. Gone.

“We are…” my companion searched through his cache of English words, gasping bent double, “very hunting!”

We were indeed. Though where we were “very hunting” could not be precisely defined. My English students, their elder brother, uncle and I, stood in no man’s land, wheezing for breath.

The uncle was known as the gurki kor, or “wolf at work.” He’d known where to find the fox. He did not know currently whether it was a Tajik or a Kyrgyz fox. Regardless, it was gone. We left the mountain and trudged down into the fallow cotton fields to hunt for rabbits.

***

What lies beyond us, creeping at the edge of our understanding—the infinite—is not just space, not just the expanse of time. It is complexity. And it is everywhere apparent. The more you look, the more there is. The deeper you go, the deeper it is.

It may be that my dreaming mind is haunted by this insight: no reality exists but what is backed by intricate mystery. In every dream I’m breathless. Sometimes I wake up sweating. But sometimes the dream continues. My arms drape behind me as my heaving chest rises toward the irreducible inhabited expanse above me. I feel terror, panic, awe. Either the infinitude of space, or the swarming of an algal bloom, or the source of both somehow fills my vision, backed by a wash of light. Finally, in a flash, the panicked self is gone. Out of all of it a unity arrives that enfolds in a single forgiveness what there was of me that feared. Then I wake up.

Is this my conception of the divine, spreading out and seeping in to fill the intricate holes of our teeming reality? Could it be that my infinite God has been, not too small, but too simple?

***

Down in the fields we trudge along lines of humped furrows, stippled by dead cotton stalks. Here we are on surer geopolitical footing, but uncertainties remain. A rabbit startles out of a furrow ahead. My student pulls up and fires, and the small creature pitches over without a cry. Now we approach across the monochrome landscape, where, in the absence of landmarks, distance is hard to measure. Where is the rabbit? When will we reach it?

Zeno’s paradox suddenly seems relevant: if we walk halfway to the carcass, then walk half the distance that remains, then half the distance still left, and so on, we’ll never arrive at the creature’s bloodied remains. We despair for a moment. It’s as if the shotgun slug has blasted the rabbit out of existence. Then, down the line of a furrow, the gurki kor spots it with a whoop: two spry ears peeking over the tilled-up soil. We are rescued, once again, from the brink. Zeno be damned. Hunters are never cynics once the quarry is spotted. And we feel for a moment, my friends and I, that we are hunters. This wild fleet world is ours to run to ground and capture. We are very hunting.

***

Back in my bedroom, awake and sweat-soaked, I do the only thing I know to do: grab at a fixed point and stare it down, forcing the infinite back to the margins of my mind. Eventually I’m able to close my eyes again without the nightmare’s nauseous grasp. This is all I can do, I think as I fall asleep, all I can ever do. Look here, look up and around. Aim where I can, and fire.