A few months ago I wrote a rather scathing column criticizingthe American prison system, specifically regarding its practical function as a punitive institution versus its theoretical function as a rehabilitative one. The article focused primarily on what politicians and lawmakers ought to be doing differently if we are to truly rehabilitate inmates and lower recidivism rates in America.

To some extent, my criticism missed the point. Yes, government money should be dedicated to the reform process. Yes, politicians should stop hiding behind legalese when determining what constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. But the point I did not make — and the point I hope to make now — is that prison reform, like any other social reform, should not be left in the increasingly incompetent and untrustworthy hands of politicians. Inmates cannot be viewed as mere statistics for policy and legislation, nor as unforgivable sociopaths who deserve punishment more than they do reintegration. They need to be viewed as humans, not monsters. They need to be seen with sympathy, not fear. Most importantly, they, like any other human, need to experience love.

Loving that which we do not understand — and especially that which we fear — is a difficult hurdle for most people. We give our hearts to what we know

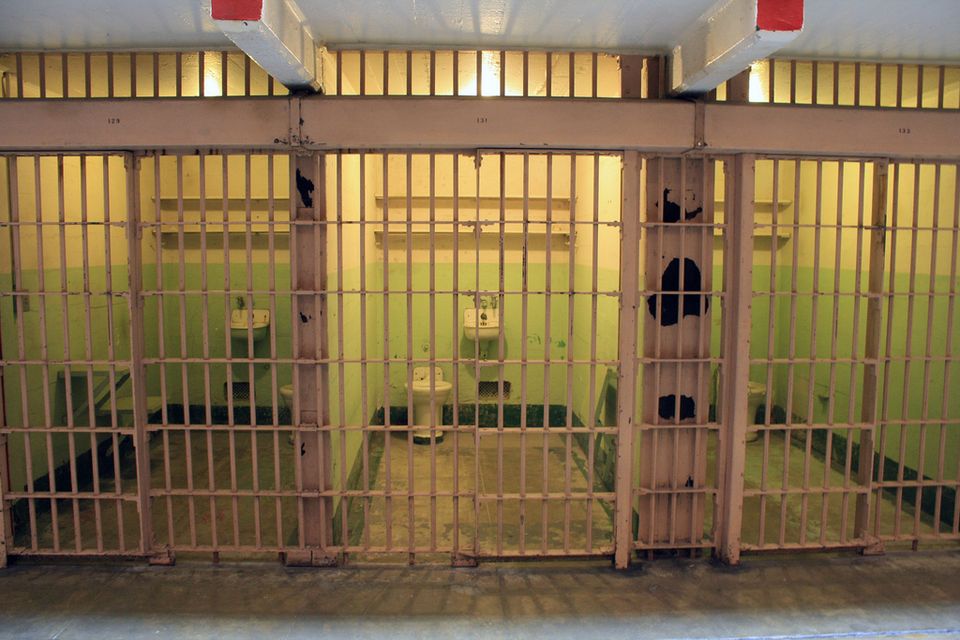

, notbecause it is so much more lovable than anything else, but because it is safe, familiar, and essentially, non-threatening. Yet the only way we are able to come to know anything is through interaction and experience. Prisoners rarely have this privilege with the outside world. Many fell victim to crime in the first place because of a lack of healthy, substantive social connection, and keeping these victims — and yes, even criminals are victims — in isolation for so many years as a follow-up, all but guarantees that such a connection will never be made. Now more than ever it seems that we are content to “lock them up and throw away the key”. We are a culture hellbent on bandaging a wound without ever applying the ointment necessary for healing. For most people in any circumstances, that treatment begins with a simple ear to listen.

Enter Between The Bars, a project initiated by the Center for Future Civic Media, which is a collaboration of the MIT Media Lab and Comparative Media Studies. Between the Bars integrates handwritten letters with standard blogging technology to provide a platform for inmates to share their stories, thus hopefully establishing even the vaguest connection to the outside world. Inmates not only have their stories published, but readers can comment, tag, and even subscribe to RSS feeds on the blog. Inmates are then able to read responses from the public, thus maintaining interaction with the very society they one day hope to reenter. This bears more significance than it may seem at first glance because many inmates have no family, no friends, no visitors, and no correspondence with other human beings. They have, essentially, been forgotten.

This is, perhaps, the greatest tragedy faced by inmates. We think of them not as individuals with faces and names, but as a population, an inventory on a distant shelf lined up and numbered, some thrown into the streets after so many years, others set to expire. For many there is no hope left in this life, and for those who believe that this life is all there is, that is a terminal blow. To no longer be seen as a human being — to no longer be seen as a life— is to be denied the essence of our creation. Through ignorance and indifference, we deny the very life we claim to be protecting when we remove criminals from society.

But giving inmates the opportunity to reach us, the very people who have rejected them, can only be powerful if those people are willing to receive them. What is therapeutic for an inmate, what is truly rehabilitative and even redemptive, is for us to once more see them as human. A man convicted of murder is a monster until we understand his own brokenness — a brokenness that, even if embodied differently, we all share. Killing someone is horrible, but is the abuse, neglect, and violence so frequently suffered by the perpetrators of these crimes any less horrible? When we are able to see the poverty in other peoples’ lives, we are able to reconcile, sympathize, empathize, and most importantly, forgive. This is not some sentimental flower-child idealism stated without consideration for the complexities of this calling — I do not mean to minimize the pain and hardship of victims of crime. But one man’s pain does not justify the perpetuation of someone else’s. Crime can never be abolished by disregarding the criminal, but only by loving him, and there can be no love without forgiveness first.

To put it more practically, the prison population should not be seen as an offshoot of society, some extra class cast to the side as undesirables. They need to be seen as part of our society, as those who require our support instead of our contempt. Giving them access to share their lives through digital social media is both a massive and a minute step towards that integration. Once more, if we are able to see inmates as part of who we are collectively, we should find it easier to see their humanity, thus making it more likely that we will find our hearts changed enough to offer them the love that most of us have never had to go without.

Unfortunately, even a private project as necessary as Between The Bars has fallen prey to the imposed sovereignty of policy and procedure. As of December 16, 2010, the site and all of its archived content has been shut down until further notice, citing administrative issues. Whether due to lack of funding, insufficient manpower, or the treachery of political agenda, we cannot say for sure, but for whatever conglomeration of reasons, the thin ray of sunlight that had briefly pierced the cold stone of this country’s prison walls has been, for the time being, stamped out once more. The blog staff hopes that the site will be back up and running again soon; perhaps even by the time this column is published. Until then, Between The Bars has done the indispensable service of reminding us that no matter the crime, no matter what wickedness mankind continues to demonstrate towards one another in haste or greed, in passion or pride, there is not one who should be denied the infallible, impenetrable, merciful sovereignty of love. That responsibility, of course, rests not with the government nor with the law, but with us.