Death is too abstract a term; nebulous and murky, accreting all life to itself with an omnipotent gravity. Poets have a knack for hearing terms we can touch. For example:

The maggot no man can slay[1]; or

Her fist of a face died clenched on a round pain[2]; or

Out of his eyes I saw the last light glide…[3]

Only a small company of poets can quicken death on the tongue like Dylan Thomas. At 18, Thomas worked a journalist beat that often took him to the morgue. If one were to judge from his notebooks of the time, death coagulated from concept to concrete in those months. Words like “scabrous”, “cankered”, “emetic”, and “spewing” gathered in his poems.However, in a letter written during this time, he treats actual death with an ironic despondency:

As I am writing, a telegram arrives. Mother’s sister, who is…suffering from cancer of the womb is dying…It lends a little welcome melodrama to the drawing room tragicomedy of my most uneventful life…But the foul thing is I feel utterly unmoved…I haven’t, really, the faintest interest in her or her womb. She is dying. She is dead. She is alive. It is all the same thing…Should I weep? For a moment, I feel, I should. There must be something lacking in me… I’m rarely interested in other people’s emotions, except those of my pasteboard characters. I prefer style to life, my own reactions to emotions rather than the emotions themselves. Is this, he pondered, a lack of soul?

I have a suspicion that his irony was just a young man’s bluster, or a device to test out the seeds of emotions he’d never experienced in youth. Notice in the last sentence that Thomas even made a pasteboard character of himself — he pondered — to examine his emotions.

When I was 18 my grandfather passed away, and I pondered, throughout that week, why I didn’t feel grief like my grandmother. She wailed and fainted when his heart monitor stopped. It was a strange, third-person perspective of myself, for which I felt a great deal of guilt in not experiencing a straight emotion. I’ve since come to dearly miss the man, and so, I think, did Thomas eventually mourn his aunt.

The notebook poem[6] he began after the aunt’s funeral treats the ceremony with ironic distance: “Death has rewarded him or her for living”; renders the woman as a “well of rumours and cold lies”; her life as “one more joke lost its point”. However, the poem’s final form five years later in After the Funeral (In memory of Ann Jones), Thomas revises his own petulant brat and notebook draft as a “desolate boy who slits his throat / In the dark of the coffin and sheds dry leaves”.

The aunt now:

…is seventy years of stone.

These cloud-sopped, marble hands, this monumental

Argument of the hewn voice, gesture and psalm,

Storm me forever over her grave…

The seed-grief which he pondered at 18 has now bloomed at 23, along with a guilt that the younger, pasteboard Thomas could neither feel nor write anything but dry leaves. He’s feeling now, even if retroactively, trusting his emotions and groping for a synthesis of the versions of himself over time. The distance is gone, but I wonder about the irony.

This period of poems also produced the famous And Death Shall Have No Dominion, which the biographer Ralph Maud reckons as a thesis statement that Thomas was testing out. The poem drafts “move from a fairly conventional agnosticism toward a personal religion of the organic processes…drawing on the specifically Christian.” Organic processes being birth, growth, and death, and then death fertilizing new life. The poem’s title is taken word-for-word from Paul’s Letter to the Romans discussing the Christian’s baptism into death with Christ, and the hoped-for resurrection. The final poem certainly ventures out in the direction of resurrection. In form, each stanza opens and closes — conceives and dies — with the refrain “And death shall have no dominion”. The line itself opens with a conjunction, signaling a beginning and end. In image, dead men’s bones are resurrected in constellations, those libraries of the ancients. And though they be “mad and dead as nails, heads of characters hammer through daisies”. Thomas’ religion of organic processes finds its pitch in that line: daisies on graves flourish on the flesh of the dead resulting in life again after death. Perhaps more importantly for the poet though is the device of flowers in poetry: the image symbolizes other poems, songs and stories. Dylan Thomas hopes his words (down to individual characters) will live again in future poets.[8]

Was that pondering, 18-year-old Dylan Thomas shocked at his lack of grief, even if he didn’t let on in the cold letter about his aunt? Perhaps the letter was only one voice of “the thousand contradictory devils speaking”, as he would have said. Surely, that petulant, pasteboard character — mad with the voice of an unfeeling sociopath — died, was killed by Thomas’ own guilt with himself, and then hammered through in the more-mature, more-living 23-year-old poet who wrote After the Funeral. These deaths-of-personality are abstract deaths and resurrections drawn down to the reek of decay and daisies. It’s powerful and useful. And ironic.

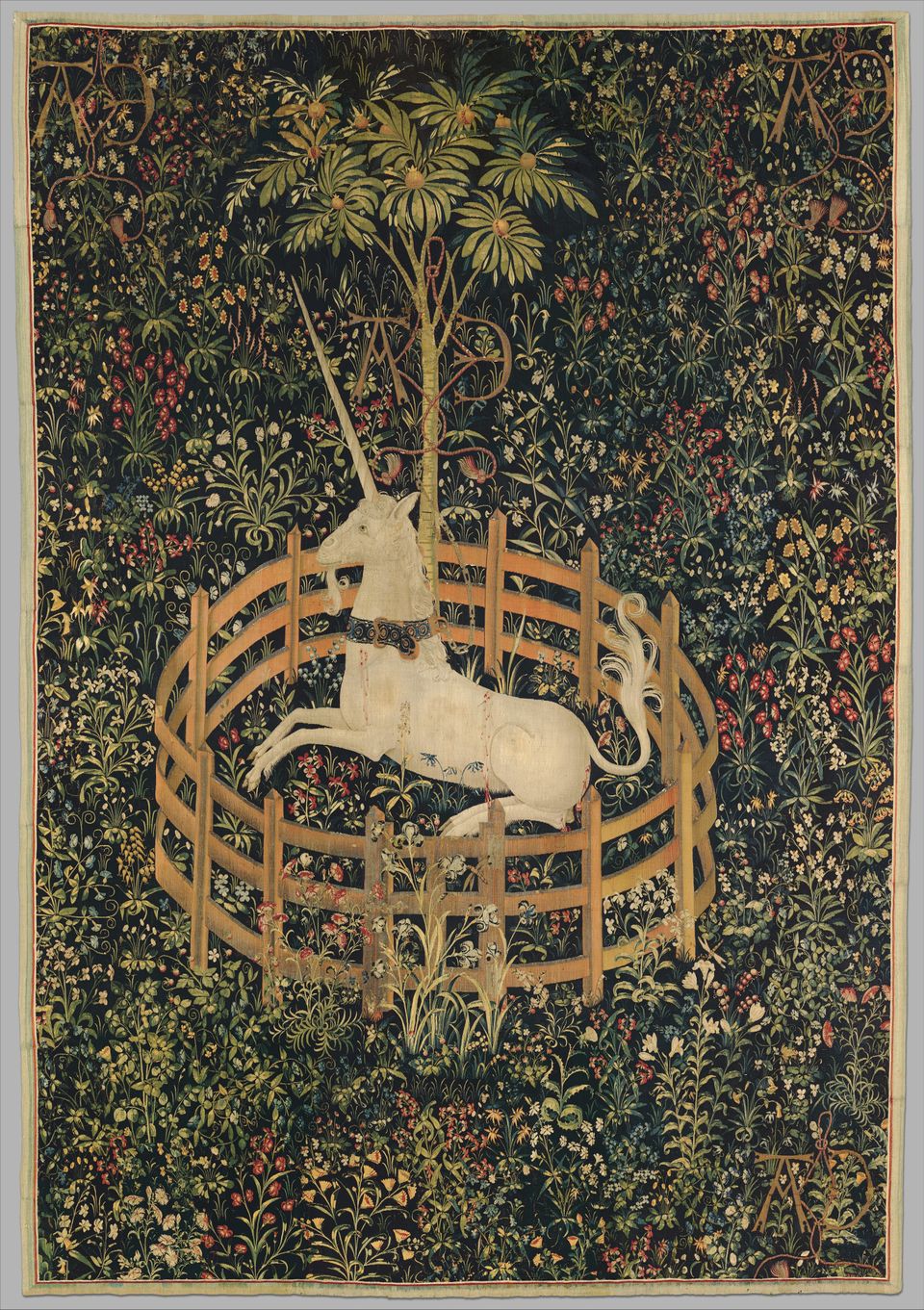

Irony isn’t bad, of course. It allows us to grasp the nebulae of death or time or memory and examine them as things, briefly, because irony is a posture toward existence that grants the bizarre possibility that things like flowers could stand in the place of gigantic death. We need it. But in the end, the metaphors of irony’s garden are ridiculous little signs. If we forget that and carry on tending our metaphors, or worse preserving them as though they lived beyond their moment; if we forget that there is real life and death beyond these things, or maybe even a god that makes and sustains these things, then soon enough, all of existence is rendered ridiculous. Elegant maybe, but absurd. A single flower exacted equitably by the blood of multitudes, as Cormac McCarthy might say.

Irony was the great gift of 20th-century literature. Generally speaking, a collective oomph heaved from mankind as if we had created an intricate automaton, set the gears winding, puffed our chests as the machine can-canned and then the damn thing kicked us in the solar plexus. The institutions were suspect. Each had participated. If a thing pointed to an abstract like patriotism or god, then the thing should be disassembled and retooled so the eventual kick would land elsewhere. Flags and borders dissolved like wafers in wine. Authors used a thing like the Eucharist ironically, to point anywhere but its original intent. See Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast.

Or see Dylan Thomas’ own This Bread I Break

Once in this wine the summer blood

Knocked in the flesh that decked the vine,

Once in this bread

The oat was merry in the wind;

Man broke the sun, pulled the wind down.

The poem ends as the narrator goes to his execution (This flesh you break, this blood you let… // My wine you drink, my bread you snap). Thomas’ religion of organic processes traces, through death and resurrection, the oat become bread become flesh become oat, bread, and man again. Death has no dominion because in twenty years I shall be another stout, young fellow, not because death itself has been deposed as Paul claimed in Romans.

That’s fair. Examine the machine. If the Church, or churches, officially or unofficially, directly or not, participated in exterminating millions of human beings, then strip the Institution down to its basic institutions. In a scrapbucket of parts, who knows where a gear like the Eucharist actually spins; what other gear it touches; what appendage and finger it raises; what it finally indicates?

In Before I Knocked, Dylan Thomas has Christ himself, a figure “neither a ghost nor man, but mortal ghost”, cut the thread between thing and abstract; between flesh and spirit:

You who bow down at cross and altar,

Remember me and pity Him

Who took my flesh and bone for armour

And doublecrossed my mother’s womb.

At 24, I traveled to Rome in March. It was raining when I stumbled into a church hoping to glimpse Bernini’s St. Teresa in Ecstasy. Disoriented with jet-lag, I didn’t realize it was Sunday morning. Mass was in progress. The church’s cold fogged my breath. The priest scowled, so I found a pew (most of them were empty). Young men nodded off next to their pious grandmothers. When the Eucharist was served, it was just a thing indicating nothing but the slightest calorie one might convert to heat in digestion. Pondering that scene now, I pity something, but it isn’t Him.

Ironically, in the scrutiny of things, death too has become abstract. I watched a TED Talk in which the scientist supposes that death is only years away from dying. As experiences and emotions merge with technology, we shall live on through programs that read and express “us”. We’ve created another automaton, but this time we’ll get it right. Death is not a final, bodily stop. Death is a pasteboard character.

For the culture at large, the Eucharist is meaningless. Likewise, the biblical language was stripped of its shrouds, and the shrouds gambled for and carried off by Dylan Thomas and other poets. Now much of the church simply trades in language-relics sold by shroud-dealers.[10] This is fine. At one time, the Romans believed the Eucharist was a literal cannibal feast. I wonder in what ways the biblical language will eventually hammer through daisies and bloom couture to make royals blush.

Will it look like Tyndale’s project: both beautiful and common, rife with organic processes (pisseth against the wall) indicating God’s majestic teleology? How will the word God be rendered? There are many contemporary attempts, most sound false with an ironic echo, still in the mode of the modernists. Is there anybody doing this effectively now (please share if you know)?

I suggest Maurice Manning who, like Dylan Thomas, employs the image of flowers sprouting from death (on as many levels as Thomas); however, watch his language, and especially notice whom the poet addresses outside of the compost cycle of things:

…if I untaste the taste

of being bossed by you

don’t boss me down to dust

may I become a flower

when my blossom Boss is full

boss a bee to blue my lips

that one drop of my bloom

would softly drop into

your sweetness once again

if I go round that way

I’ll know the doing means

to you what it means to me

a word before all words

This poem is one of 78 poems (Bucolics), rendered in the same manner with no punctuation and simple language. Not once in the whole book is there a smack of irony, which in our notch of history is like a carpenter building a house without nails. Each poem is a simple voice considering a thing and then asking and interacting with God about the thing. God here is rendered as “Boss”, not with the modern awareness that God is an ineffective appellation; no, because the narrator is much too innocent for that, but “Boss” is an earnest attempt to name the god who must be there. It’s respectful, affectionate, indicating an authority that can be trusted. It’s like Manning found that scrapbucket of parts the moderns left in an attic, and instead of passing it over, he has found them beautiful, too beautiful to be without design; and if design then tragic, being scattered without the machine of their purpose; and if tragic, then please God, please Boss, be there to make sense of these things.

Perhaps it’s as simple as tracing the words of Dylan Thomas’ thesis, back toward the beginning, before the conjunction. What is the independent clause that comes before “and death shall have no dominion”? Maybe then we’ll know Boss. Then we’ll know.

[1] Find Meat On Bones

[2] After the Funeral (In Memory of Ann Jones)

[3] Elegy

[4] Maud, Ralph. The Notebooks of Dylan Thomas. New Directions, NY. 1967. p 18.

[5] Ibid. p 21

[6] Ibid. Poem 6, p 168

[7] Ibid, p. 24

[8] Perhaps the ultimate proof of this came when a young Robert Zimmerman changed his name to Bob Dylan, after Dylan Thomas, resurrecting the poet for another generation.

[9] It’s interesting to note that the early notebook version of this poem was titled “Breakfast Before Execution” and the narrator is Christ.

[10] This statement could be read as a dangerous generalization. Please realize there are many beautiful communities of faith engaging the task as Karl Barth laid out in Evangelical Theology: “facing squarely the question of the proper relation of their human speech to the Word of God, which is the origin, object, and content of this speech.”