While crossing Fifth Avenue and 39th Street I could see, between silver buildings and above the traffic dotted with yellow cabs, the spire of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral. I had called my wife, who grew up Catholic, about the possibility of going to a Good Friday service. Even as a Presbyterian, I long for Holy Week services. Since this was to be Cardinal Edward Egan’s last Good Friday service, I waded in to St. Patrick’s, docking the TV reporters wanting to interview parishioners, trying not to get in the way of tourists taking photos, and managed to slip in a pew quietly though I had to step over a lady in a white trench coat to get to my seat. “My apologies,” I said to her, and she smiled. “You are very welcome, dear,” she said. The trick to being in a huge church building, I suppose, is not to sit behind a pillar, although at St. Patrick’s, there’s a wide-screen plasma hung vertically on every pillar. The cross at the center of the altar place was shrouded in red cloth, and that red echoed throughout the church, like some abstract remnants of a fashion show repeated over and over in every pillar. As I looked about, all the faces around me seemed rather familiar. But of course, I did not know anyone: they were mostly the faces of ordinary New Yorkers living not in Manhattan, but in Queens and Brooklyn.

The choir with operatic solos opened the service, and Cardinal Egan began the three hour service with a meditation on the “last words of Jesus.” He sat down in the center of the Chancel, as he is still recuperating from his illness earlier in the week. This homily, too, will be his last words at Saint Patrick’s. He is to retire now, with the successor already named (Archbishop Timothy Dolan). With his red cap and flushed skin, he spoke eloquently though the audio sounds bounced about the chamber, disappearing into the vast clerestory full of refracting stained glass windows, forcing me to lip-read a bit. He spoke of the gift of forgiveness, relating the days leading up to Good Friday. “The power and the gift of forgiveness cannot be underestimated,” he stated. Jesus walked the path toward the cross, knowing that every act to forgive, to bring mercy, he would suffer for.

I stayed for about an hour, which meant I lasted barely into the second reading (of seven). But I had promised to treat myself to an exhibit up Fifth Avenue a bit – the extraordinary paintings of Steven Assael at Forum Gallery.

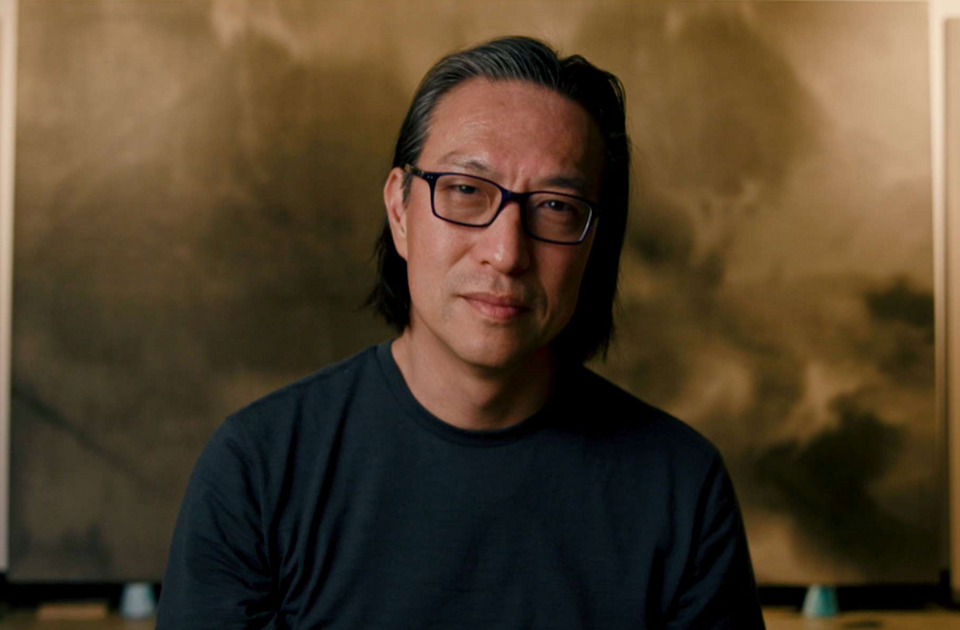

I had dinner with Steven Assael’s pastor, Pete Scazzero of Queens’s New Life Church, once. Pete asked me what I thought of Steve’s work. I told him, “Steve is probably the best painter alive.”

Since the passing of Andrew Wyeth, there are very few painters that come close to Steve’s abilities, to make that grand statement back then reasonable to me now. Possibly Janet Fish and George Tooker would challenge, but the gravitas of Steven Assael’s works, and the profound wrestling that goes on in his paintings, make his exhibit a must-see.

As I said that to Pastor Scazzero, my mind also imagined many of his congregants coming to view Steve’s exhibit. One recent Assael exhibit was of nude figures half-dressed in Goth outfits, with tattoos and cigarettes. The fact that these figures seemed to me to represent contemporary Adam and Eve would not convince many religious folk to champion Steven’s work. Then there were paintings of his dying father in the exhibit after that. Steve’s careful observation of the last days of his father, the utter agony that you could sense with every painting, capturing breath with every sketch, would deprive any the luxury of sentiment that art can merely be peripheral in our lives, and exist just as decoration. Not exactly Sunday School art.

To really appreciate Assael’s abilities, one needs to understand how exiled our culture is from great art. If you walked around the White House today, or any institution that track portraits throughout the centuries, you notice that after about 1930, the quality of portraiture declines dramatically. Starting from the magnificent copy of Stuart Gilbert’s George Washington and David Martin’s animated Benjamin Franklin, the execution and depiction of historical figures wane in quality, and the recent portraits of presidents are dismal efforts, lacking any presence of the person, or conveyance of historical significance. (One notable exception is Aaron Shikler’s Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis painting in the ladies’ lounge area.)

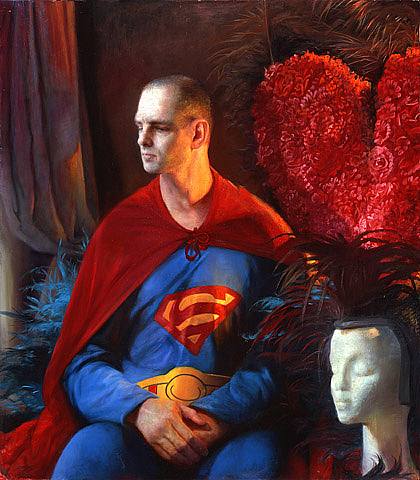

Steven Assael’s portraits come close to the best of portrait traditions, but his subject matters are not conventional status quo sitters or dignitaries. They are ordinary human beings, teenagers, fellow congregants, and subway riders. They are given costumes to wear, like Superman’s cape in one of this exhibit’s paintings, or carnival headdresses and feathers in Costume Party #1. They may be nude figures, faces seemingly too shy to be drawn, and yet so delicately and affectionately depicted, holding a pair of binoculars or a camera.

In this exhibit there’s also a rare self-portrait – a gaze of an artist with his innocence retained, bright and curious eyes looking up at you, as if startled to find you looking back.

And then there is Crowd #1, recently completed, which is the grand centerpiece of the exhibit. In this piece are apocalyptic masses; all seem to be brought there by some otherworldly reason, but not startled and seemingly resigned to their fate. In front, a boy wearing a blue shirt with a large star holds a macaque yawning (or screaming?). Two sisters comfort the boy, possibly whispering into his ear. The masses seem to be waiting – but for what? A triangular hat in the middle with some mystical and magic ritual design catches my attention, but then each face begins to float to the surface like imaginary faces of neighbors, distant cousins, street musicians, or maybe even librarians. They seem so familiar, yet completely unknown to me.

The light shines on all of their faces, though, and even through fear, they all seem to be drawn to it. Then I realized that these faces actually reminded me of the faces I’d seen at St. Patrick’s. They are urban dwellers, ordinary folks who I pass by everyday in the subway cars.

In our lives, we work so hard to dress up and cover the inner malaise, like in the painting of Superman’s costume that fits awkwardly on the man’s lean body; the outfit cannot mask the doldrums of our days, the dark depressions of our psyche. Steven Assael captures our modern tales humbly as a fellow journeyman, depicting the world he sees as a friend, a teacher (his Pratt Institute figure classes are legendary), a husband, a father, and an artist. Though his paintings are dreamlike, they are actually more real than imagined, more hope-filled than depressed. He is a surreal master of reality, and re-humanizes every subject by infusing every portrait with a deeper longing for a world to come.

And so, the way he handles paint rivals any masters of the past, or any contemporary abstract expressionists. He is precise and inventive at the same time, delighting our eyes. With every line of his pencil he loves, with every brushstroke he affirms, and with every work he teaches us what a good painting can do: uplift, challenge, and reveal our exilic condition. Exactly what we need to see and re-experience in a Holy Week, in which an extraordinary death touched ordinary lives, so that cruel death upon the Golgotha Hill would not be the end, but the beginning of a journey. All of us, like in Assael’s paintings, are huddled in urban exile, with a golden light cast ever so gently to reveal our true humanity.

Steven Assael: Paintings & Drawings is on view until May 2, 2009 at Forum Gallery, 745 Fifth Avenue at 57th Street, Fifth Floor, in New York City.