Every Tuesday afternoon we’re featuring the work of an artist in our community to support them in cultivating a new audience, to give voice to their oft-unknown studio practice, and to build a diverse roster which participants in the contemporary arts conversation might reference.

Mark Sprinkle is a Virginia-based artist, craftsman, writer, and cultural historian, whose interdisciplinary work is focused on the question, “How do works of art help us see and be ourselves more fully?” Raised in Texas, he is a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Georgetown University, and earned MA and PhD degrees in American studies from the College of William and Mary; there he studied the sociology of culture and focused on how artworks embody complex relationships in domestic settings. Since 1996 he has been an independent painter and frame-maker, also regularly writing and speaking on the role of creative practices in cultural mediation and renewal, especially in the area of science and Christian faith. He was Senior Web Editor and Senior Fellow of Arts and Humanities for The BioLogos Foundation, and is now convener for makeRVA, the IAM-affiliated arts community in Richmond, VA. You can learn more about Mark’s work as a writer and artist at his website.

Sprinkle, on his work:

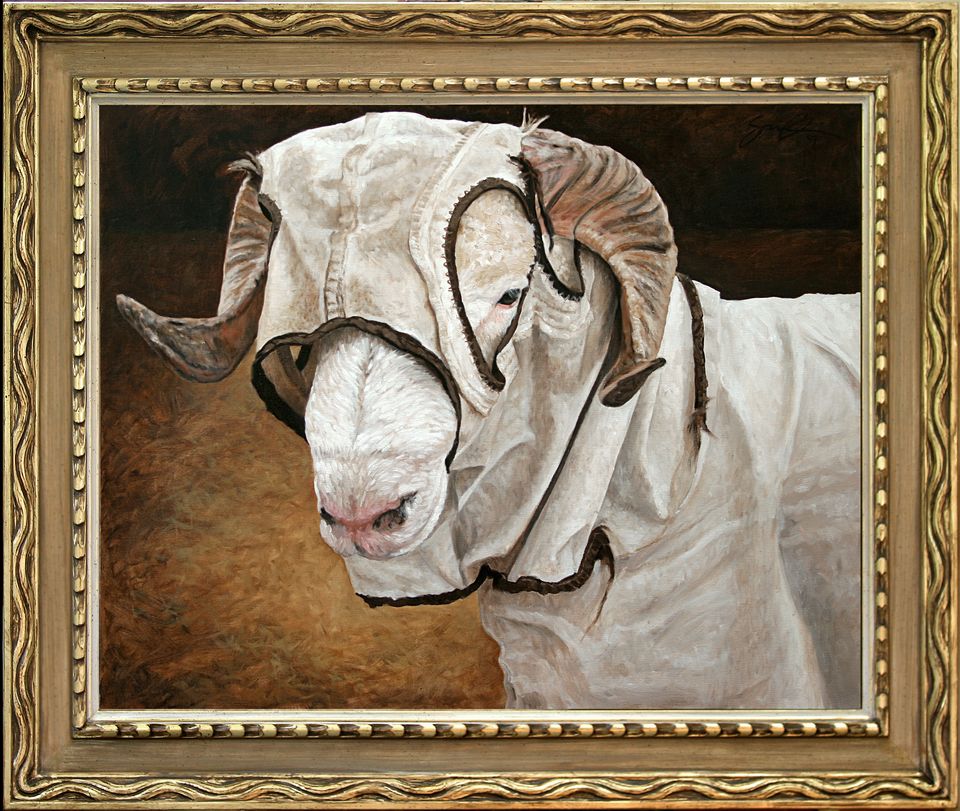

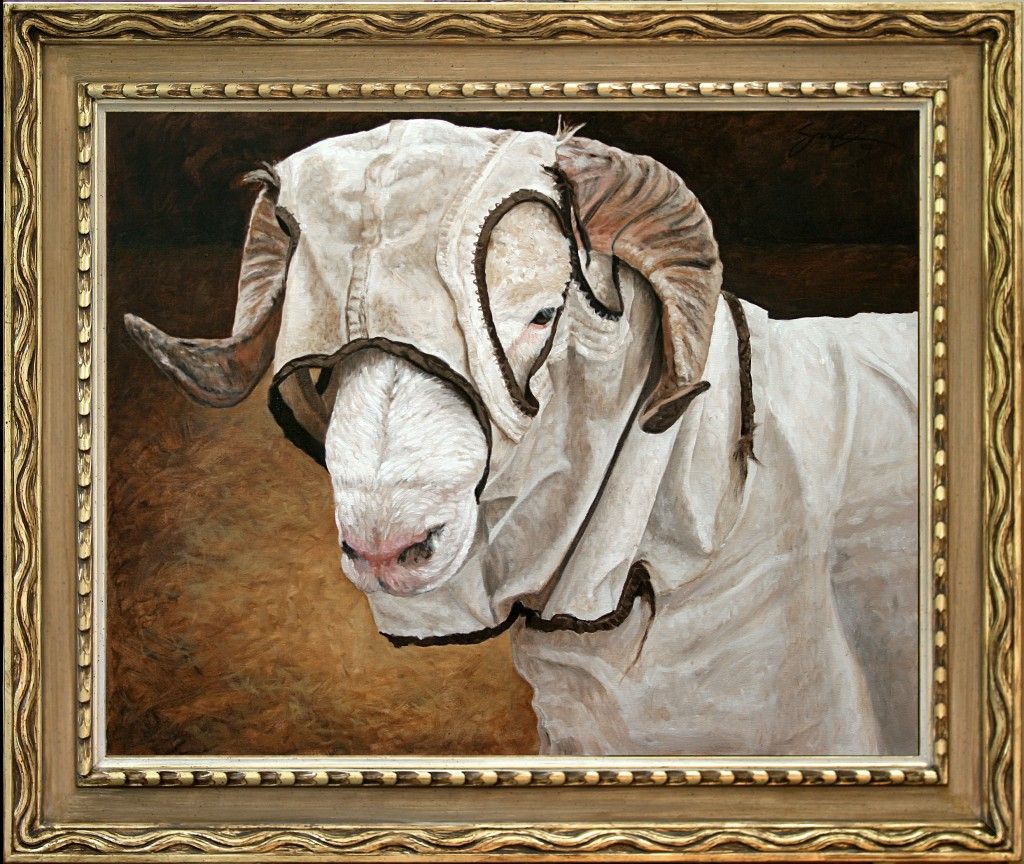

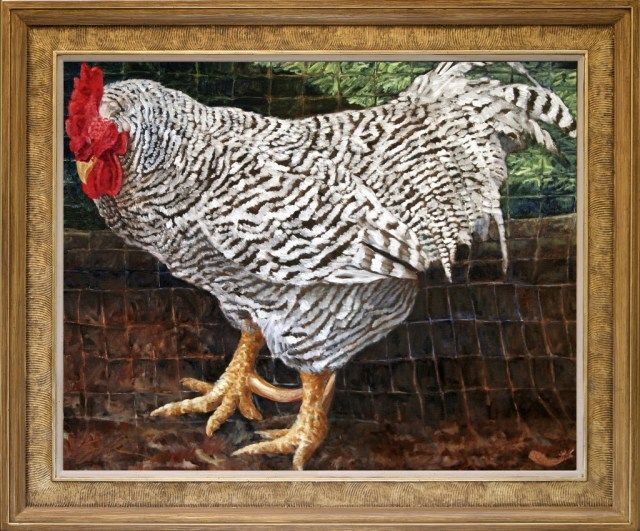

The occasion for talking about my work here at The Curator is the recent opening of a retrospective show at the Billy Graham Center Museum at Wheaton College, which will be on display until the end of October, 2014. Through the Eyes of a Shepherd: Seeing the Incarnation through Animal Imagery brings together over two-dozen of my “narrative” paintings—fable-like works that use animals to invite the viewer into specific scenes, most of which are also part of a larger story (contemporary shepherding and local agriculture in Virginia) that I’ve been exploring since about 1999.

From the introduction to the show:

In nearly every global culture, folk-tales, songs, and visual artworks have used animals to offer sometimes-subtle, sometimes-forthright critiques of human character and relationships. Depending on familiar types (clever foxes, prideful roosters, foolish sheep, and stubborn goats) in complex moral situations, these stories offer just enough imaginative distance to allow a wide variety of hearers and viewers to find themselves in the narrative, and to recognize patterns (good and bad) in their own interactions with others. Of course, the Bible and historic Christian art, too, are filled with images of animals as stand-ins for humanity, giving us renewed ways to recognize God as creator, provider, and redeemer, and to see ourselves as the Lord’s diverse and often wandering flok.

The more than two dozen works in this show speak to the development of a couple of central commitments in my studio practice that may have more bearing on thinking “Christianly” about art than does that explicit connection to traditional forms of Christian story-telling: first, that even familiar images and metaphors, traditionally rendered, continue to carry rich, complex meaning; and, second, that art can be deeply powerful when it both emerges from and is then re-integrated into the ordinary, physical rhythms of life—not least those of our living spaces.

All too familiar

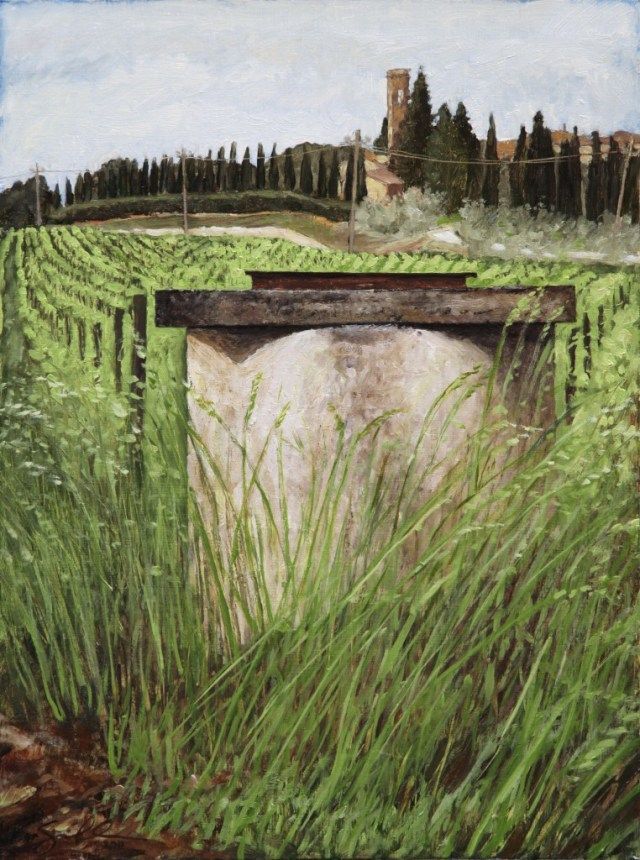

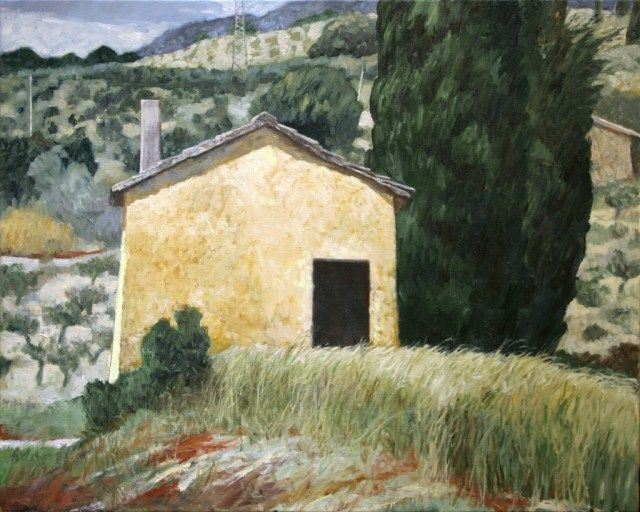

While I have a deep appreciation for and have been an advocate for abstract, installation, and experimental art, I have always been drawn to more traditional media, forms of representation, and even subjects in my own visual and symbolic processing. Beginning with some early work in which the rural landscape of my youth was juxtaposed with the gritty and violent urban setting of Washington DC in the late 1980s, the landscapes I have painted have been specific places I have lived or travelled through–transformed by a long human presence, but still beautiful. I spent a lot of time looking at and walking on various kinds of agricultural and wild terrain as a child in Texas, each space telling a story about the way working the land shapes it: think about linear row-crops, patchwork fields, barns, implement sheds, and farm houses—whether occupied or (just as often these days) abandoned.

Each of those stories was deeply overlaid with my own memory, family history, and identity. The way images of landscape connect us to such personal and cultural histories was part of my academic research (think of Thomas Cole’s paintings of the Holy Land as much as his images of the Hudson River Valley), but also my own experience: the small watercolor “postcards” I would paint for friends from the beach, or, later, for family to record our travels to Italy and give as gifts to friends who visited the same locales. Landscape paintings like these were representations of the fields and forests and farms and towns and mountains I saw in Europe, in Texas, in Virginia, in Colorado, but even more than that, they were representations of seeing them with people I love. Relationships were inscribed in the art, embodied via images of the spaces and scenes we saw together.

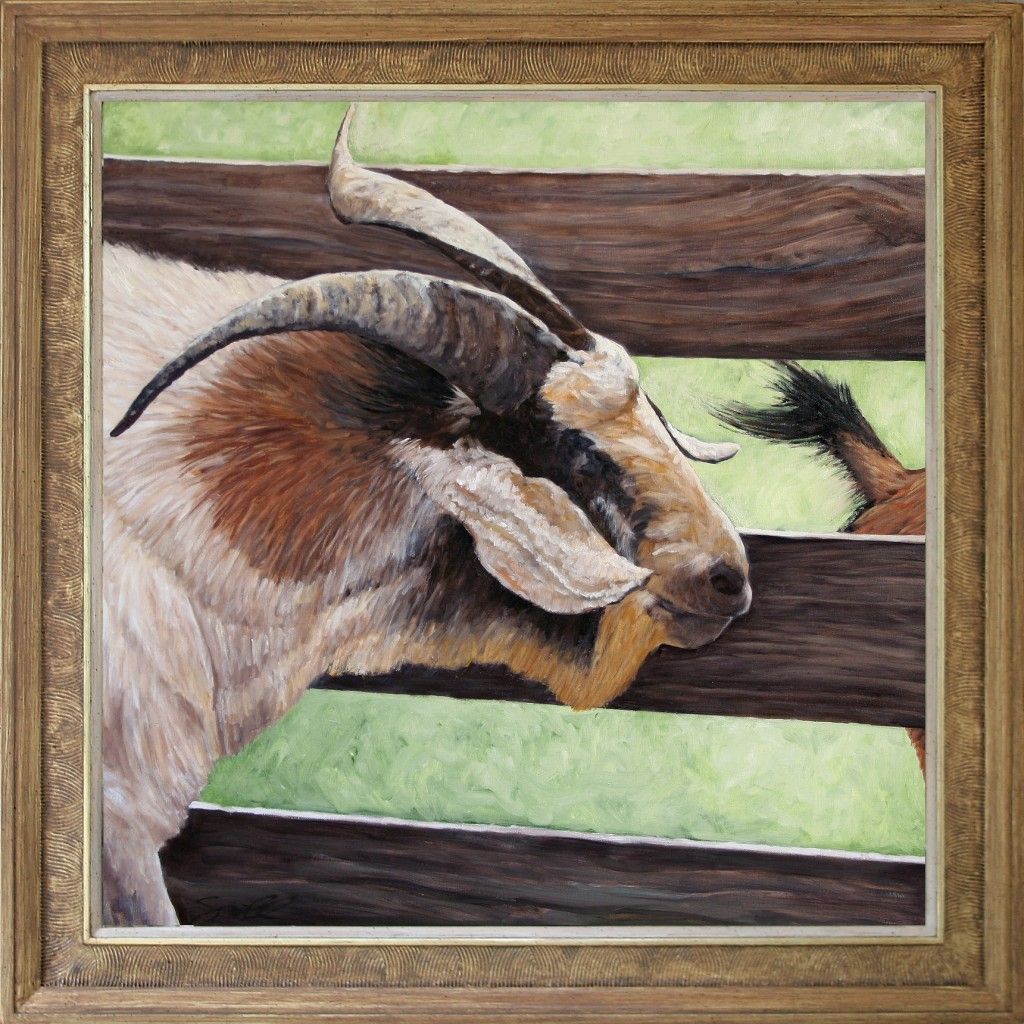

Likewise, the animals I paint have for the most part been those that present themselves to me where I have lived and worked: I have painted dogs, sheep, goats, and chickens—creatures about as far from avant-garde and “edgy” as you can get, and which have so many familiar associations (especially in Christian culture), that we run the risk of not actually seeing them, at all.

Yet these have their own stories to tell, too—often through what I have come to call “found parables.” Beginning with getting to know “the duck that thought it was a chicken” on my grandfather’s farm near Corpus Christi, the decidedly unnatural commingling of creatures that occurs at the household agricultural scale almost inescapably presents us with scenes that speak of likeness and difference, boundaries and transgressions, the caged and the free. The even more complicated and near-ritual activities of state fairs and livestock shows also confront visitors with strange images that beg for engagement and interpretation, if we’ll take just a few minutes to look and pay attention, seeing past what we think we already know. In fact, the centerpiece series of this exhibition is the working out of the idea that paying close, anti-nostalgic attention to the dynamics of shepherds and sheep in the globalized present can shed a different light on even the tried and true (or “trite, if true”) Biblical imagery of lambs and flocks and shepherds.

Indeed, just giving them their due (both the sheep and the paintings) may be the real challenge for art-savvy contemporary viewers, especially, when met with such “traditional” imagery and subjects: we are so used to a constant stream of new images and products, of the latest recombination of materials and techniques into novel visions, of being presented with things that break new ground in their level of spectacle or subtlety or ironic detachment, that we don’t actually take the time to look at and get to know the slow, ordinary, and mundane world that most of us actually live in, much less see the physical or spiritual richness in what we take to be too-familiar or passé. Daniel Seidel has called upon the church to withhold judgment of challenging contemporary art until we have taken the time to receive it on its own terms and look for intimations of truth via an aesthetics of common grace; it is just as important that we approach work that appears unsophisticated, simple, or even superficial with the same attitude of humility and openness until we know what it is trying to tell us.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Not just the what but the where

A second emphasis of my studio practice that actually gets lost in this installation at the Billy Graham Center Museum has to do with my commitment to ordinary spaces as well as ordinary subjects—my belief that an ethic of hospitality is central to the way all artists (but especially Christian artists) can find the deepest connections and community for themselves and their work. In short, I think the intimate space of the household is an incredibly rich (and demanding) place for artists to target our creative work, because the task of creating art that people will live with on an ongoing basis requires us to bring our whole human interpersonal, social selves to our art-making as well as our technical craft and creative vision. More than that, it requires an implicit willingness to make our art a “place of meeting” between all our stories and those of others.

I am most interested, then, in how my own work can enter into that space of negotiation as a gift, still always being “my work,” but also becoming something more than I could have imagined or fully intended, and helping those who interact with it regularly tell their own stories more deeply and personally. I do not want my work to be so idiosyncratic that it is about me exclusively. Especially when they are experienced over and over again in intimate rooms, ordinary subjects, landscapes included, can and do serve as touch-points for whole suites of memories, especially when integrated into the daily practice of life. Therefore, I want to create works that can bear and reward sustained attention, but that are also explicit and approachable enough to offer themselves and the stories they imply to and through daily practice, even literally in passing—helping frame identity from the background of domestic space.

There is much more to say about how that actually happens (the phenomenology of how art becomes a means for others to extend hospitality and openness when it is integrated into the physical space of their house or apartment was one focus of my dissertation), and about the importance of the “objectness” of artworks in an increasingly digital age, but the critical piece for me is that pursuing the possibility of local (even hyper-local) integration and impact may well mean trading a wider public for a deeper one, and that, as a painter and believer, I have found that to be a worthwhile bargain.

Since Duchamp certainly, but perhaps even more pervasively in an age and culture that so loves irony and seems to make it the measure of seriousness as a “creative,” the question in many art contexts—especially for the uninitiated—is “How do I know I can trust that this work is true, that this artist is not just pulling my leg, or manipulating me for gain or spectacle?” We can be fooled by surfaces, either into thinking there is more there than there really is, or in thinking there is less there than there really is. Both intention and reception matter, and an ongoing dialogue between artists and community is a prerequisite for such trust to develop, as well as being a remarkably fertile, if currently underexplored territory.

Therefore, despite the wonderful exposure for my paintings and thinking about art that the Wheaton show (and this profile!) affords, I am still focused on the possibility of art facilitating ongoing local relationships, not primarily transmitting or communicating my message or brand to the widest possible audience. When the show is done, many of the pieces will go back to the household collections where they live (e-mail me if you’d like one to go home with you, as well), and I will continue to paint small-scale works and mostly connect with people and sell works at weekend house shows. But I will also continue to fiercely advocate among younger (and older) artist friends, whether near or far: dare to be ordinary; dare to be local; dare to be small.