Every Tuesday afternoon we’re featuring the work of an artist in our community to support them in cultivating a new audience, to give voice to their oft-unknown studio practice, and to build a diverse roster which participants in the contemporary arts & faith conversation might reference.

I had the pleasure of interviewing Jesse Lee Wilson for the magazine. Our conversation follows below.

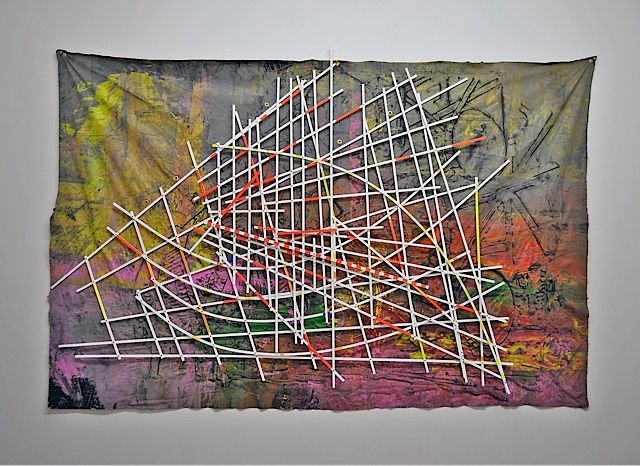

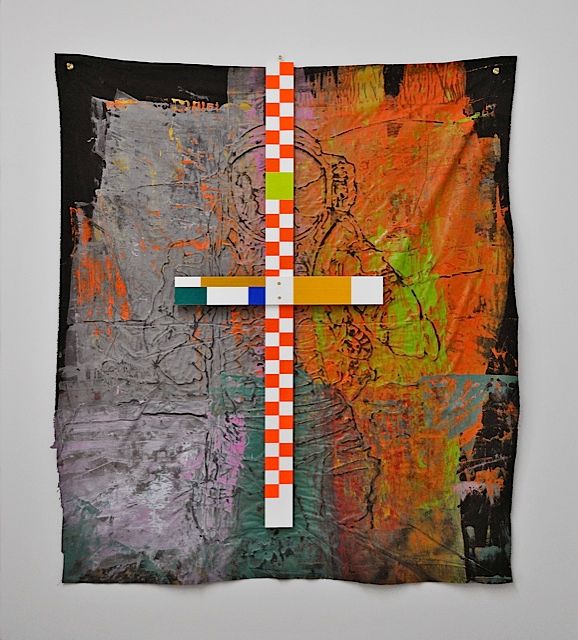

Jesse Lee Wilson is an artist who lives and works in New York City. His practice grows out of the intersection of social engagement with design, architecture, and contemporary art. Working primarily in processes that blur the line between painting and sculpture, graphic design or photography, he seeks to use the representation of an object as a device to investigate what is most essential in the object’s identity. Graphic symbols and illustrative images play key roles in his investigations. Wilson’s work primarily employs materials utilized in industrial and construction applications, which he puts to work in ways that subvert their pedestrian nature and allow for flux within a given composition, in homage to the ways a material life may be re-invented.

After several years traveling as competitive snowboarder Wilson shifted to pursuing a degree in art and design from Alfred University. He went on to earn an M.F.A. from the University California Santa Barbara, focusing his efforts on working closely with the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara to create a long-term exhibit for children investigating graphics and visual communication. After relocating to New York he worked for the artist Jeff Koons as a special projects developer researching new materials and process to be employed in the artist’s work.

Wilson also initiated a pilot project, the New Path Art Program in collaboration with System Architects and All Angels Homeless Shelter. Many of the New Path projects engage artists who were homeless or in transitional housing, exploring opportunities for their expression of identity and personal narrative as a vehicle to engender dignity and empowerment through a creative practice.

Currently Wilson directs The CHILL Foundation in New York City. This foundation is a social justice initiative of the company Burton Snowboards and has a mission to provide opportunities to at-risk and underserved youth to build self-esteem and life skills through board sports. As an artist Wilson sees these board-sports as a type of drawing activity where the breadth and diversity of lines created represent possibility in the lives of the youth they work with.

Meaghan: Tell me about the process of devoting yourself and your time to making art? How has this decision played itself out in the studio over the years? Have your desires and practices changed?

Jesse: From an early age, I became interested in the idea of personal language and expression. I wondered what it looked like for a person to have an authentic, successful language to communicate their thoughts to the world, even if they weren’t adept to standardized learning. In that way, art, for me, felt like a successful medium. As a kid, it’s amazing when you find a new way of speaking.

Then, of course, I enrolled in art school—my experience of it started off very narrow—I thought I wanted to focus on one specific practice (ceramics). Over the course of my time there, I became very open to trying lots of media. My appreciation of this new diversity was filtered through the work I made.

Those foundations gave way to a very broad wanderlust, a way of looking at the world through art.

How has this taken form over the years?

In my work it’s very apparent that I’m a child of the 80s: the language of advertising, movies and media was very graphical in nature then. I couple that influence with my understanding of architecture, how we are oriented in spaces, the world around us—that consistently plays into everything I do.

As I mentioned I was originally interested in ceramics, but I discovered that I was enamored with the history and practice of painting. Painting creates a static image that arrests you in a particular time and place, and while I was attracted to that, I kept making things that wanted to come out, engage space and imply movement. Now I’m making sort of kinetic images, things with dimensionality that require as much engineering as they do poetry.

How did peer critique and conceptual instruction during your MFA catalyze your movement from painting to installations and so forth?

My undergrad was heavy on craft and technique; we were engaging the hand, organic materials—the emphasis was on tactility. I decided that I wanted to do my MFA in California and that’s where the specifics of my practice really started to emerge. I took my background in working with tactile materials and coupled it with design, architecture, entertainment and imagined spaces.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Can you remark on a couple of specific pieces that are a reflection of that integration?

I worked on an early inflatable project called “Oasis,” which was essentially a huge, elongated, inflated tent situated on the steps of the Santa Barbara Art Museum. It was meant to usher you into what became a lounge/retreat space. It was the creation of a temporarily built space, but it was also a sort of painterly intervention on the steps of the art museum itself.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

What have been major difficulties (personal, professional or conceptual) you’ve overcome in doing this work?

The major issue at the center of most of my art-making struggles—which has been constantly reenergizing but has required reinvention—is figuring out where I most belong. Around the time of the end of graduate school, I realized that while I wanted to engage the contemporary art scene, I was very restless and resistant to entering into the gallery scene or art market. I felt myself constantly trying to figure out what my career trajectory would be. I wasn’t drawn to where the critical mass of activity in the contemporary art scene was assembling, so I continued to make things for a long time, not knowing where they would end up in the world. Recently that’s changed, but it took me a long time to understand where my place in the art world was. That was difficult for me.

Because your work is so place-oriented and so particularized in its setting, translating ideas and concepts into objects without knowing where they’re going to be, would be very hard. In order for your work to come to pass, there are a number of factors that have to be in place before you can even start. I can imagine NYC presents a whole other set of difficulties because it’s so market driven and space is such a commodity.

Grad school is this free space where you’re afforded limitless room for experimentation..the West Coast is prized for its wide-open spaces. My first question when I came to NYC was: where do I pick up? My first answer was to condense types of intensities, sort of miniaturize the work I was doing, and translate it in a dramatic way. I wanted to make things that were very saturated; something that could exist in a gallery but that had the vast feel of the large outdoor work. This was influenced by texts I read like Poetics of Space by

Gaston Bachelard. He talks about miniaturing the world—I wanted to know if I could pull that off.

How do your spiritual practices inform your work?

I ask myself why there is a visual language in my work. Someone once described my work as harsh, sharp, and almost dangerous, with turned up contrast, and I wondered what that said about me. I’m someone that does have a hunger for a natural stasis, a space that’s uninterrupted, but I’m using this language that’s incredibly man-made.

When I was growing up I wanted to be a Formula One race car driver. I wanted speed. I find myself meditating on statements Ayrton Senna made (which I heard in the recently-released documentary about his life) about about driving the loop. The circuit became a tunnel; he had to react instinctually. I indentify with him. I think about imperatives and speed when I’m in the studio. In the same way, if you look at The Lord’s Prayer; it’s full of imperatives “Thy kingdom come” & “Thy will be done.” There’s a real sense of urgency about these things. I think I can relate to Senna’s impulses which are ultimately bridled by my faith. I try to bring all of that into my work.

How would you compare the satisfaction of making a successful work of art to, perhaps, the satisfaction Senna felt when he won?

Our souls are looking for both awe and joy. I think both of those sentiments are at the heart of a victory. The artist experiences a similar feeling when a piece is done. In some of the best work I’ve made, I was completely alone, but I still felt like someone, something was participating in it with me—in the awe and joy. That drives you; it leaves you wanting more.

I think fear is a part of the conversation, too, though. A friend called me this morning—it’s so clear to me that her identity and soul is that of an artist—but she has the hardest time accepting that because she doesn’t think she has the skill or talent. She has a fear of being who she was created to be.

She read this book called The Artisan Soul and had a self-described breakthrough. The book talked about how fear is plaque on our lives. I started to think about momentum, and I thought , plaque only builds up where there is no movement, when there is a lack of pace. She talked about stuff that was looming on the horizon but that she was moving away from it. Wherever you’re coming from with regard to your faith, you’re running towards God or away from God, but you can’t deny that God is at the center of that activity. That’s sort of how my practice feels.

Do you think you’ve had guides on your walk as an artist?

Most of my guides have been outside of the realm of the fine arts. One of my guides was architect Samuel Mockbee. He said, in a spirit of boldness, that architecture needed to engage people’s lives. I’m constantly pursuing a place where truth, if it is real, has to be put into practice. Mockbee’s belief was that architecture has to be both beautiful and serve a physical need. As an artist, I make things that are fantastic in nature and not clear in their function, but I’m drawing off of a proof, the testing of something. All of my work is tactile, you want to feel it, test it, know that its true. That leads me.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

More of Wilson’s work can be seen here.