Every Tuesday afternoon we’re featuring the work of an artist to support them in cultivating a new audience, to give vision into their oft unseen studio practice, and to build a diverse roster which participants in the contemporary arts conversation may reference. This Tuesday our featured artist is Jay Walker, with whom I was able to chat. Our conversation follows.

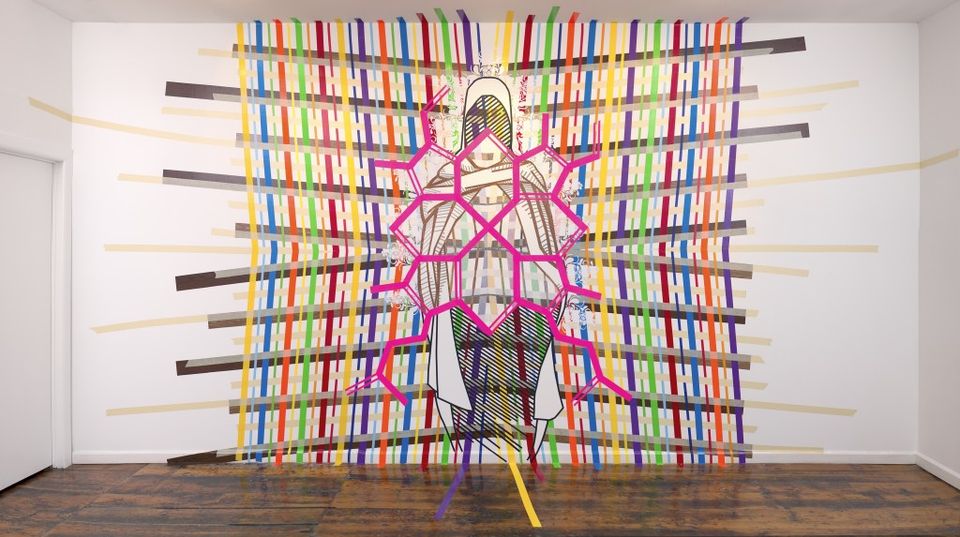

Jay Walker’s Bio: Jay Walker is a Philadelphia-based multi-disciplinary artist creating tape installations, mixed media painting/drawings, and carved sculptures. He has a BFA from Texas A&M-Corpus Christi and a MFA from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Walker regularly exhibits in both group exhibits and solo exhibits. He has been Solo exhibits at the Abingtion Art Center (Abington, PA), James Oliver Gallery (Philadelphia), Gordon College (Wenham, MA) and the Crane Hall (Philadelphia). He has also been in group exhibits at Pentimenti Gallery (Philadelphia), DCCA (Wilmington, DE), Space 38|39 (New York, NY) and Baden-Wuerttemberg Arts & Cultural Center (Heidelberg, Germany). Walker also regularly curates exhibits and happenings.

Meaghan Ritchey: Tell me about the process of devoting yourself and your time to making art? How has this decision played itself out in the studio over the years? Have your desires and practices changed?

Jay Walker: Creating things is imperative for me. I can go a few days without doing it, but after that, I become uncomfortable with myself. Because of this urge, I continue to make art, but I am not very disciplined in it. I hear of artists that have mechanical like days of certain hours devoted to their studios; I am never going to be that person, even though I regularly try to be.

My college mentor, Bruno Andrade, who passed away last year, use to call me a “spurty painter” because he would find me painting in the studio for 12 hours at a time for 5 days straight, but then I wouldn’t come in for a week. He wanted me to be in there everyday for a set amount of hours. I just wanted to paint all of the time, and so when I would work, I’d forsake everything and work until my body gave out, my family and friends needing to see me.

I’m like one of those guys on Deadliest Catch: they go to work for a month but then they are off for two. It appeals to me—immersing myself, taking it as far as I can, and right before it destroys me, pulling back to rest. Feast and famine. Because of this I keep myself away from entanglements that need me regularly. I have a wife that understands this about me. It is something that I am loving about my recent installations. The galleries normally give me a limited amount of time to accomplish this giant project, so if I don’t completely focus, it won’t get done, and when it is done, I rest. It’s important to know my own rhythm and not resent myself for it.

MR: How did peer critique and conceptual instruction during your MFA catalyze your movement from painting to installations and so forth?

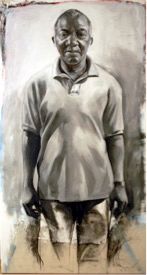

JW: My time at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts was so strange. I remember it like I remember the first grade. I had no idea what was going on, and because of that, I don’t think I really understood what I was doing. At the same time, it was a mind expanding experience. I showed up to PAFA thinking I was going to impress everyone with my drawing abilities. It was like showing up to the Olympics and trying to impress the other athletes with how muscular you are. They were just like, “so what? What are you going to do with that?” So in my second year, I latched on to a concept of creating artwork all about a janitor, Frank, that worked on my floor. I started by drawing him, and before I knew it, I was creating paintings, an eleven foot statue, a video, and framing a photograph of him and giving it to everyone I knew. I explored obsession in portraiture and discovered that I didn’t like being confined to a medium. I wanted to create whatever I wanted to and didn’t want to be beholden to what I was doing the week before.

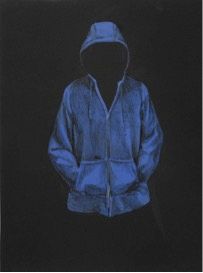

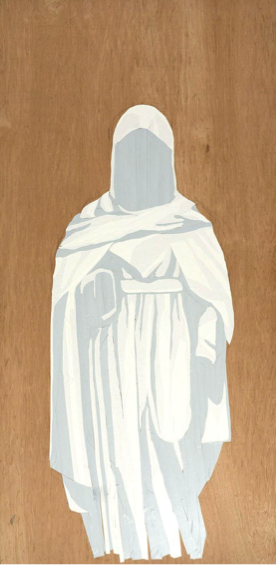

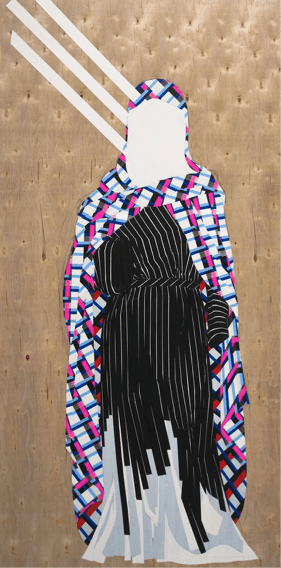

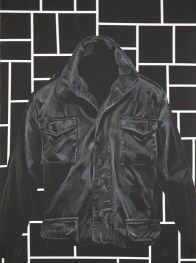

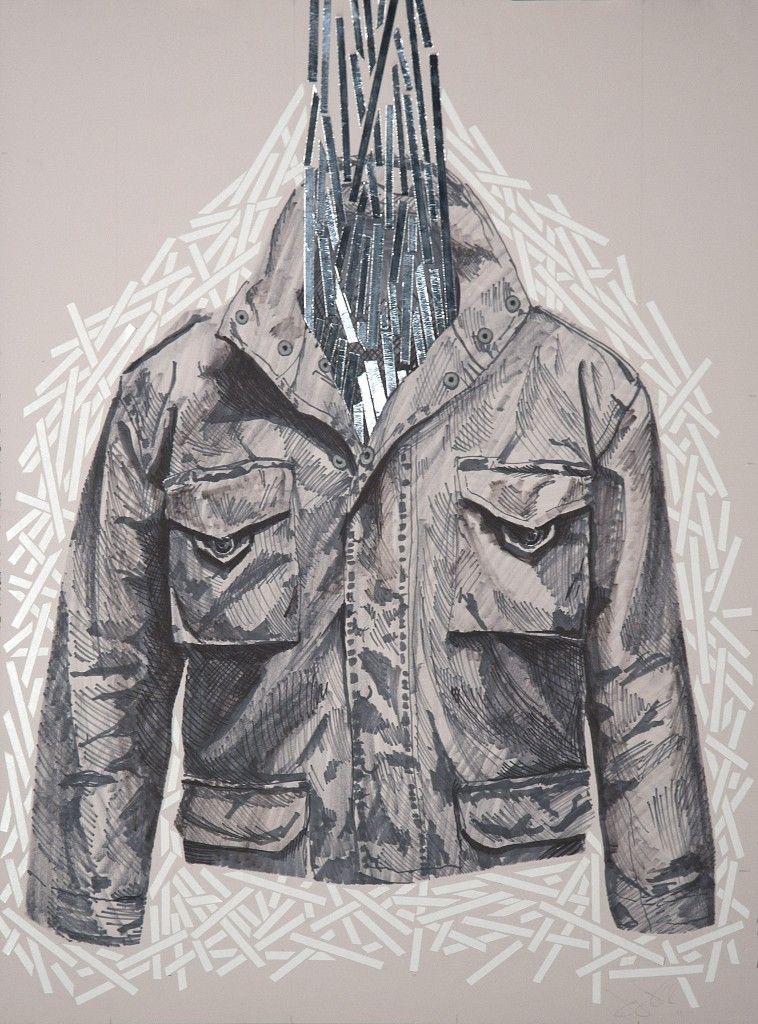

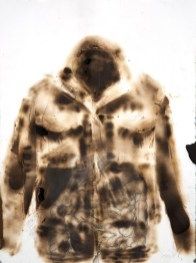

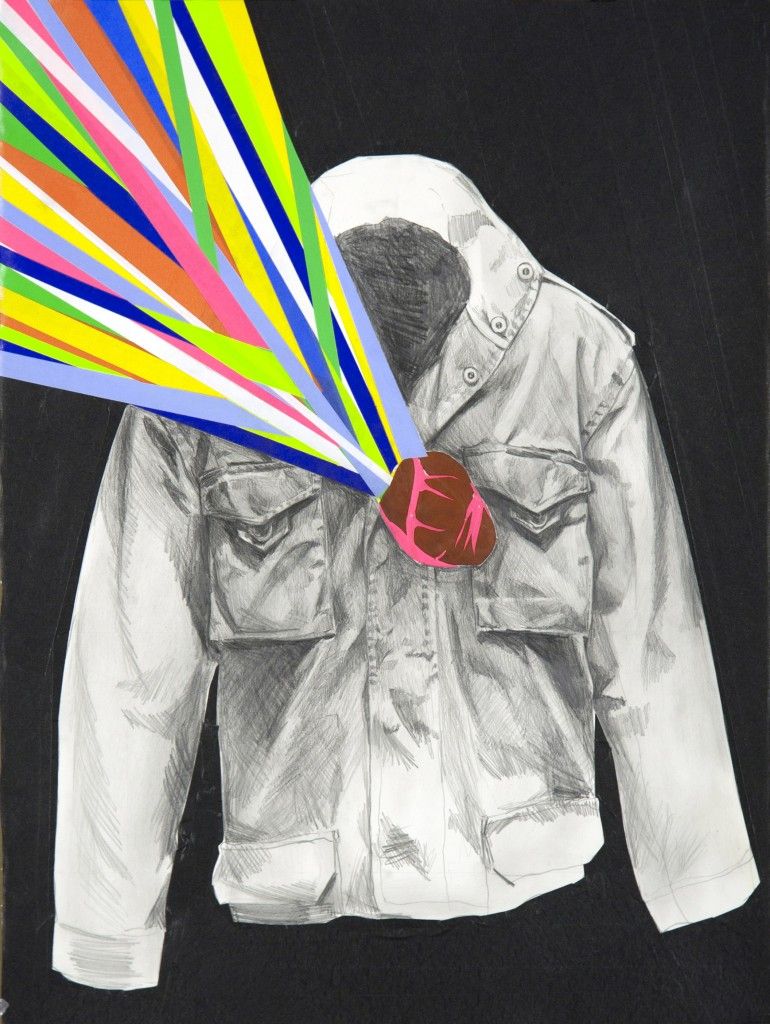

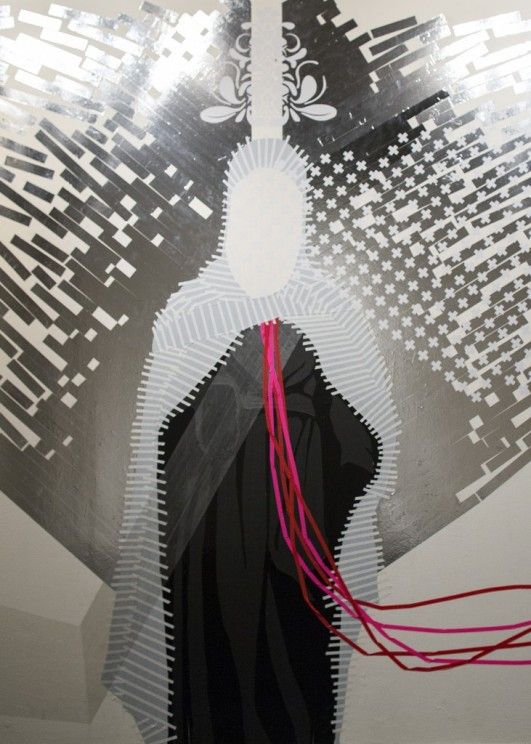

Once that freedom was established, I began exploring counterintuitive conceptions in my work. I was obsessed with portraiture and the figure, so I asked myself what happens if I remove the person, well then I just have clothes, so I did a series of clothing paintings and drawings. Then I was using tape to make sure the work’s lines were tight and clean, and then I realized I liked how the tape looked on the paper, so I began drawing with tape. I only liked to paint portraits of “everymen” and everyday clothing, so I explored a cloak and tunic that I saw showing up in religious iconography. My work had been mostly desaturated and plain,then it became technicolor and full of pattern. I was focused on my work being archival, so what if I worked in a way that the tape become a throwaway ball of tape after the exhibit? I am in the middle of transition right now in my studio—with the tape everything is clean flat line, so I am now painting with colorful wood dye that is looser than watercolor, which is a real mess. I love looking at the opposite approach and following where that rabbit trail will take me.

Here are examples of this progression:

Peer critique is an interesting relationship.It only can happen with certain people, someone who I have developed that relationship with over time. I need their fresh eyes telling me what they see which allows me to separate myself from the work just enough to see what needs to happen next. I need to figure out the work, but doing that alone can be stifling. If someone starts telling me what I need to do, I stop listening, which considering my nature is humorously hypocritical. Out side of that, criticism is something to either be laughed off or absorbed, and the former should be the case most of the time. I’m on a path that requires things to seem ridiculous at a point. If everything is reasonable and understandable to all people all of the time, I am not going anywhere. Test everything, hold on to what is good, reject what is bad.

MR: What are major difficulties (personal, professional or conceptual) you’ve overcome in doing this work?

JW: The biggest obstacle is a fear of my own stubbornness. Am I really supposed to be doing this or am I just not letting it go? Of course, this voice is louder when I am not getting attention, but it changes when I am having some success, then it just calls me a phony. And then there is the lack of money, but we all know that story. Poor starving artist. Then you make money and suddenly you aren’t legitimate. But I regularly remind myself, if I wanted to make money, I could’ve in a different career (I have a high view of my abilities), but I chose the other path and an old dead poet told me it would be worth it.

At this point, I should point out that I married an amazing woman, who pushes me even when I want to give up and is comfortable with a spartan life when it comes to that. If you are going to be an artist, marry well or not at all. When it comes to everything else, I have learned that I have to be patient with myself. The artist life is a war of attrition and the one still standing at sixty has a chance of victory. The one who runs headlong into battle and doesn’t understand why the “Art World” does not raise it’s white flag immediately is not going to have a good time of it. Maybe the work I am making at the moment isn’t that good, but maybe it will lead to something important? Explorers tend to have to go through some rough terrain to get somewhere meaningful. So I just keep creating and know that questioning the worthiness of the work is a waste of time.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

MR: Do you think you’ve had guides on your walk as an artist?

JW: I try to let everyone be my guide. In other words, what can I learn from observing every person I encounter, artist or not? In the past, I have had mentors, but at the moment, not really. Not to be morbid, but a lot of them died last year, Bruno Andrade in Texas, Sidney Goodman at PAFA, and my best friend David Sacks. The only one out there is Mark Anderson, who is the chairperson of the art department at Baylor, but we don’t get to see each other much these days. Bruno taught me that I had to work very hard. Sidney taught me that pretension is crap and being honest with who you are is the only means of creation. Mark taught me not to believe the hype. And to define what David taught me would be ridiculous. I initially went to him to learn how to function business-wise as an artist, but that was just the tip of the iceberg.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

More of Jay’s work can be seen at his website.