The holidays are happy because they force us to leave the warmth of the illusion of adulthood and watch our years of therapy slide down the sink with the scraps of Christmas dinner and our dignity, as our pretensions to maturity explode into the sibling rivalries we founded at the age of three. A Christmas Tale and Rachel Getting Married – both black comedies about cripplingly dysfunctional families – let us take a sullen consolation in the fact that our dysfunction doesn’t reach that height. As the tagline of Rachel Getting Married half-reassures us, “This is not your family . . . But this is your family.”

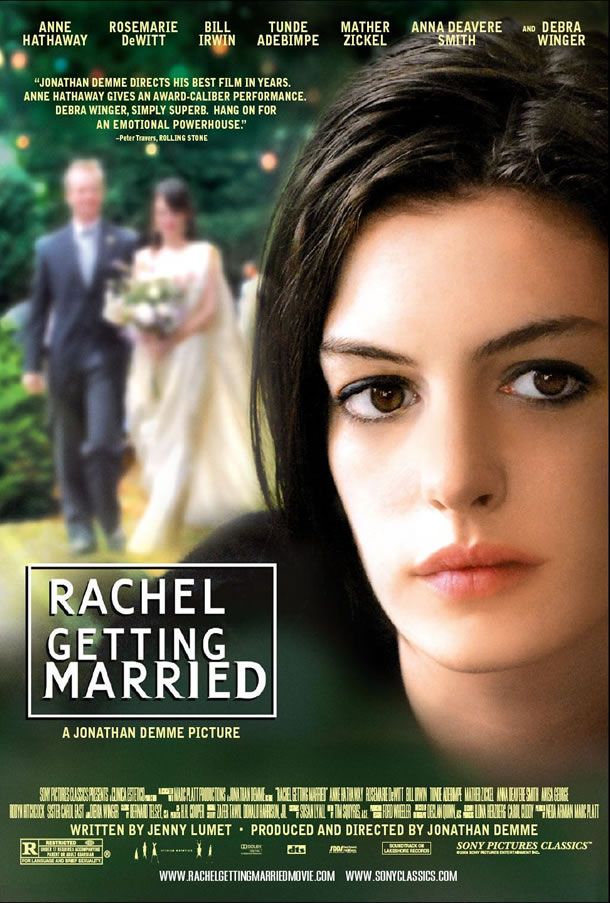

In A Christmas Tale, matriarch Junon Vuillard (Catherine Deneuve) has just been diagnosed with cancer and needs a marrow transplant. She must choose as donor either her mentally tortured grandson or her shiftless son Henri (Mathieu Amalric), whose sister Elizabeth (Anne Consigny) had him banished from the family. There is rage, rivalry, paranoia, depression, alcoholism, adultery, and a sprinkle of anti-Semitism and incest thrown in to top off the holiday cocktail. Rachel Getting Married takes another festive occasion and inserts Anne Hathaway as Kym, a chain-smoking bulimic on leave from rehab for the wedding of her sister Rachel (Rosemarie DeWitt).

It’s no coincidence that films about dysfunctional families are set against a festive backdrop, as their titles like to make quite clear. It’s because this is when all of us, no matter how humdrum our family dynamic, feel imperfection most acutely – the imperfection of our human relationships and the imperfection of the moments that are supposed to be the happiest.

Festivities force us into physical proximity and make us face not just everyone else’s ugliness but our own ugliness mirrored in them. Kym’s deepest wound is knowing she’s wounded her family, but who caused her wounds and who reopens them? She blames herself for the car accident that killed her younger brother, but she blames her mother for letting her drive. Rachel can’t forgive her, perhaps because Kym’s self-loathing makes forgiveness almost impossible, but Rachel’s judgment also deepens Kym’s self-loathing. Family violence is a cycle without a beginning or an end. There are no innocents and you can never trace the bitterness to a single source. Humanity itself makes human interactions imperfect and this is true for everyone – yes, even for the tediously stable.

Human imperfection also mars the moments we want to be perfect, and we cling to the belief that weddings and Christmases should be one long unbroken moment full of peace and joy and love. But talk to any savage Christmas shopper or hyperventilating woman trailing lace, and they will you tell that some imperfection always mars the moment. Perhaps your brother-in-law will begin to pummel your brother beneath the dining room table, or your nephew will attempt to stab his mother, or your wife will find she could have loved your cousin, or your sister will decide to use her wedding rehearsal toast to complete an Alcoholics Anonymous assignment to make amends.

We compound our discontent when we assume that other people’s Christmases and weddings reach perfection. We think that no one else’s family teeters on the edge of mental instability and no one else’s siblings make drunken, inappropriate displays. They do, of course, and that is why these films console us.

But there’s another reason these movies are set in festive settings, and it’s why they don’t leave us feeling hollow. There are always moments of perfect, unadulterated joy. Rachel Getting Married ¬≠is full of them – always rough, uncut and rambling, as if it would be wrong to cut them short. Rachel’s private dance with her groom and the toasts at the wedding rehearsal are beautiful – corny songs and circuitous jokes and all. In A Christmas Tale, the moment comes when Henri wakes after his bone marrow extraction and tears groggily down the hallway in a hospital gown to sit with his mother. These moments can’t last long enough because you know they’ll end: Kym’s mother will announce she’s leaving early, or Kym will take the microphone and stand up and murder the moment. You cling to these moments because you want them to last as long as possible for these people, just like you want them to last as long as possible for you.

The most dysfunctional families have their own odd kind of closeness. Maybe it’s just enmeshment, but they love each other in their own awkward wounding ways, and it’s because these little moments heal. You can’t erase the memory of all the wounding things said to you by the people you love, but you also can’t erase the moments where you love each other – imperfectly, but still it’s love – in spite of that.