I recently moved and repeated a routine that has accompanied every move I have made since I got married—defending my personal library. Every time we move, and are confronted with the effort and expense of moving so much paper, my wife asks the quite fair question, “Do you really want to keep all these books?” Since I am a keeper of books both professionally as well as personally, I consider this to be a serious and profound question. It goes beyond my personal preferences and peculiarities and gets to a fundamental question being asked of libraries in the digital age: Do we need to keep all these physical books?

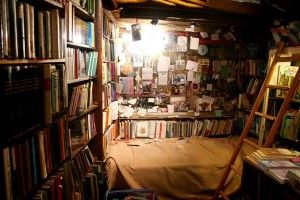

The author and critic Umberto Eco says that when people are confronted by his own substantial library they often say something like, “What a lot of books! Have you read them all?” His answer is, “No, these are the ones I have to read by the end of the month. I keep the others in my office.” This reply, he says, “on the one hand suggests a sublime ergonomic strategy, and on the other leads the visitor to hasten the moment of his departure.” Within this witticism Eco is making a point that a library is not just “a mere storage place for already-read books” but is, rather, “a working tool.”[1] So the first part of my apologia for my library is that it is a repository of resources for my education, edification, and entertainment—let’s call it my advancement in knowledge.

But these resources are not reducible to their intellectual contents. The books in my library are objects with temporal and spatial dimensions—they are connected to times and places of creation, acquisition, and consumption. One who appreciates the associative value of books can share the sorrow of the struggling novelist in New Grub Street who is forced to sell some of the books from his library:

Many of those vanished volumes were dear old friends to him; he could have told you where he had picked them up and when; to open them recalled a past moment of intellectual growth, a mood of hope or despondency, a stage of struggle. In most of them his name was written, and there were often pencilled notes in the margin.[2]

We read books, not merely texts. And much more than the pure content of a text is mediated to us through a text’s material incarnation. Peri- and paratextual meanings, from both inside and outside a bound book, adhere. Some of these become essential to our encounter with the text, such as the ways in which a publisher frames it. Others are accidental and/or incidental, such as what happened to a particular book while I was seated in a pub in Oxford. So the second part of my apologia concerns all the things that have grounded my advancement in knowledge to the material world.

Finally, when I consider the books on my shelves I am reminded of a character in novel by Charles Williams. After pondering a bookcase, he says:

If they came alive … if they are alive—all shut up in their cases, all nicely shelved—shelved—shelved. We put them in their places in our minds, don’t we? If they got out of their bookcases—not the pretty little frontispieces but the things beyond the frontispieces, not the charming lines of type but the things the type means. Dare you look for them …?[3]

This could be referred to as the spiritual dimension of books and their aggregates, libraries. When looking at books on the shelves and in the stacks, some of us sense something more—the meaning that remains beyond the material, the actuality that exists before the accommodation, the presence that permeates certain books that we peruse. By way of affirmation or negation, of what is said, unsaid, or unsayable, the library refers to realities that are not manifested in it.

Augustine described time as being present to us in three ways: the presence of past is experienced through memory; the presence of the present is experienced through perception; the presence of the future is experienced through expectation.[4] My library—which sustains and shapes my memory, enhances my perceptions of the present, and informs my expectations—enables me to have a richer experience of temporality. And what is true for an individual library is true for the library of a community. Like books, libraries are both means and metaphors for knowledge: they reveal and represent to us what was, what is, and what is to come.

While I have not avoided the transition to books in digital form, these are at the same time easier to move and loose. Perhaps in the future we will realize better ways to remember, perceive, and experience the materiality of digital books so that these, too, will manifest for us our libraries as well as their histories. But for my last move, my digital library remained in the cloud without much thought given to its past, present, and future.

[1] Umberto Eco, “How to Justify a Private Library,” in How to Travel with a Salmon & Other Essays (New York: Harcourt Bruce & Company, 1994), 116-17.

[2] George Gissing, New Grub Street (London: Smith, Elder, and Co., 1891), 257.

[3] Charles Williams, Shadows of Ecstasy (Vancouver, B.C.: Regent College Publishing, 2003), 47.

[4] Augustine, Confessions, trans. R. S. Pine-Coffin (New York: Penguin Group, 1961), 269.