Spoiler Alert: Major elements of the plot are discussed in this post.

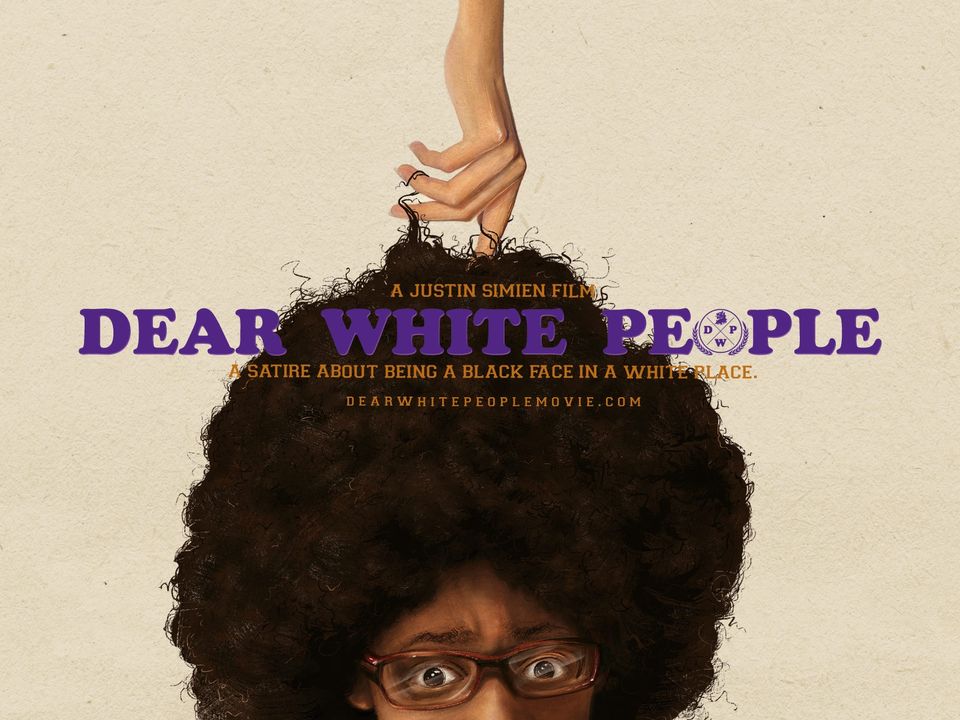

The film Dear White People is a provocative piece of social commentary that represents a post-Obama generation come of age. Satirically portraying what it’s like to be a black student at an elite, predominantly white institution of higher education, a “black face in a white space,” the movie explores the performances and negotiations of identity on a college campus. As a recent graduate from a predominantly white college, I found Dear White People to be over-the-top and too real all at the same time (perhaps the intended goal of a satire?). More importantly, this movie captures a historical moment that coincides with a Millennial

post-racial malaise and the encroaching politics of white resentment.

The story revolves around four black characters who attend the mostly white, fictional Ivy-league Winchester University. Samantha White is the artsy, “radical” student who hosts a campus radio show called “Dear White People.” Lionel Higgins is the nerdy and openly gay aspiring writer who doesn’t fit in with any group and attempts to break through at the student newspaper. Troy Fairbanks is the clean-cut, secretly pot-smoking, outgoing head of the traditionally black residence hall and happens to be son of the Dean of Students. Coco Connors is the “diva” from Chicago’s South Side who’s trying to assimilate and achieve fame. As the story unfolds, with Sam surprisingly beating Troy for head of house, and then culminates with a controversial “blackface” Halloween party, the identities of the four are further complicated with the biggest twist coming in the development of Sam’s character.

If there’s a villain in the movie it’s Kurt Fletcher, who embodies “privilege” as the son of the university president and as head of the campus’s elite humor magazine. In one particular scene, Kurt and Sam get into a heated exchange in the cafeteria of the traditionally black residence hall about who belongs where on campus. Sam sarcastically apologizes to Kurt: “On behalf of all the colored folks in the room let me apologize to all the better qualified white students whose place we’re taking up.” At one point, Kurt exclaims: “I believe the hardest thing to be in today’s workforce is an educated white man.” When I heard Kurt’s words in the theater, they were all too familiar. It’s moments like these when Dear White People really gets the racialized tensions in today’s college campuses. Swimming against a stream of post-racial consciousness, minority students are confronted by a growing sentiment among their white peers that it is they who are systematically disadvantaged in today’s age of multiculturalism, political correctness, and there-being-a-black-president.

But aren’t Millennials more inclusive? Kurt’s post-racial frustrations may appear to be exaggerated until one is reminded that a recent study found that 48% of Millennials think “discrimination against whites is as big a problem as discrimination against racial minorities.” Dear White People scratches below the surface of 21st century campuses to show that we haven’t progressed that far when it comes to race; it scratches to reveal simmering tensions and often claws to render dramatically explicit—sometimes overwhelmingly so—what goes on implicitly but would not necessarily be said in real-life dialogue.

One of the most striking scenes is a film within the film. For a class project, Sam creates a short film called “Rebirth of Nation,” a reimagining of the classic (and white supremacist) American film, “Birth of a Nation.” Sam’s short silent film depicts whites in white-face hurling insults at Obama after he wins the presidency and consequently weeping and losing all hope for life when he gets re-elected. After the screening is over in the classroom, Sam’s white peers are speechless—noticeably uncomfortable. This moment in the film, with its subtle and sharp commentary, is reflective of a post-Obama generation disillusioned with post-racial fantasies and having to respond to white reactions to demographic changes. Where some see progress, others see and experience institutions’ inability to address racial legacies. Perhaps this is best exemplified by Winchester University’s proposed “Randomization of Housing Act,” the cause of Sam and her radical friends’ initial protests. The housing act would diversify—break up the traditionally black resident hall—all housing in theory but most likely hurt black students in practice.

To come of age after Obama became president is to live in a world of progressive contradictions. On the one hand, there are more people championing marriage equality. On the other hand, we have the American courts gutting affirmative action and voting rights. The growing consensus appears to hold that we’ve moved beyond race and best thing to do is stress color-blind equality. In addition to this, coinciding with the rise of Obama and demographic changes in the country, there’s an emerging politics of white resentment. Flying in the face of history and accounts of economic and social power, whites come to be seen as the “new” disadvantaged group discriminated against. This is the backdrop of kids going to college after Obama. College tends to always involve heightened identity confusion and exploration. Dear White People takes the perennial themes of college-age identity confusion, exploration, and belonging and places them in the context of a post-Obama America.

What director Justin Simien says about black identity in the development of the four main characters will certainly raise questions and debate. Blackness is portrayed as a diverse array of performative strategies. Particularly noteworthy, and the driving force of the film, is Sam’s transformation in which she apparently renounces her radical “act,” an act pressured in part by her black love interest, Reggie.

In the early part of the film, Sam neatly fits into an agitating protester archetype: calling out the president, distributing a subversive pamphlet called “Ebony & Ivory,” and making quips (e.g. “Dear White People, the amount of black friends required not to seem racist has just been raised to two. Sorry, your weed man, Tyrone, doesn’t count”) on her radio program. Yet, we later learn that she is secretly sleeping with one of her class TAs, a white man named Gabe, and that her ailing father—whom she says little of to others—is white. These loves in her life push her towards a crossroads in which she is forced to confront an identity she has taken up, one that has crowded out her loves and authentic interests.

It’s Gabe, Sam’s white lover, who attempts to define who she really is: an anarchist, an artist at heart “who actually likes Ingmar Bergman more than Spike Lee.” In this intimate conversation in her room, Sam appears to accept the claim. This is confirmed by Sam’s change of hair and dress, and by what we surprisingly discover is her involvement in creating the invite for the scandalous blackface Halloween party. The party becomes a canvass for her to draw out what she knows is already present on campus, and she shows up with her camera to create her next short film for class.

Does Sam’s shift away from her radical “act” represent a repudiation of black radicalism on the part of this film? One possible way to read this is to see Simien—maybe unhealthily—pitting radicalism against anarchy/art and the role of the artist. A broader question that can also be asked: does this movie re-center whiteness in the character of Sam? Perhaps the liberative potentials of Simien’s black characters remain constrained.

If you want Dear White People to be primarily a catalogue of microaggressions or a pedagogical tool to explain all of the intricacies of racism to white people, you will likely walk away disappointed. The director himself has stated in interviews that he sees the film as preeminently about identity, about the theatricality and presentational nature of identity. If you watch Dear White People as a campus satire about identity in post-Obama America, then it has something to say. Hopefully Simien and others will say more.