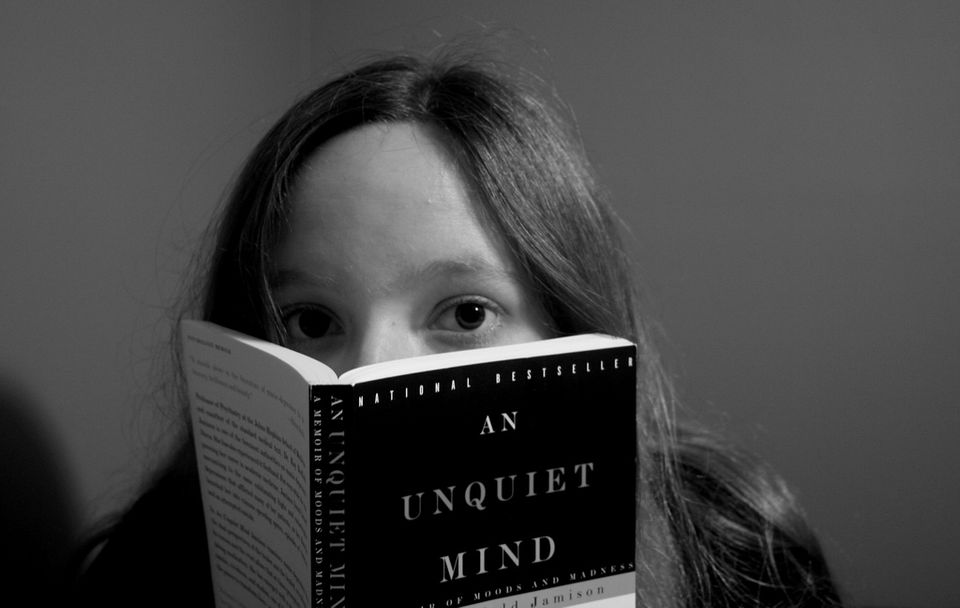

I met your kind in college. It was in Kay Redfield Jamison’s An Unquiet Mind. Your pages were musty, your spine well-broken. Your words engulfed me, lassoed me in the undertow of Jamison’s death-thoughts and hallucinations. You suited her telling just right. When I closed the cover I knew Jamison, could feel the tumult of living bipolar and discovering it so late in life.

What happened next? I did not seek another incarnation of you. Instead, I met your cousins, the Personal Essays. They were enchanting, always touching my arm and pulling me aside to confide some story well worth my time through its hilarity or gravity. My favorite of these cousins? Bernard Cooper‘s “Winner Taking Nothing,” Adam Gopnik‘s “Bumping into Mr. Ravioli,” James Baldwin‘s “Notes of a Native Son,” Joan Didion‘s “Goodbye to All That,” and E.B. White‘s “Once More to the Lake.”

Then your sedate, worldly wise, and pondering cousins came to dinner. These were the books of Literary Journalism. How I liked meeting Tracy Kidder‘s Mountains Beyond Mountains and Old Friends, Truman Capote‘s In Cold Blood, the nonfiction sections of Joseph Mitchell‘s Up in the Old Hotel, and Anne Fadiman‘s The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down.

Next to these sat their children, sun-burnt and bespectacled. The Researched Essays. They brought bug jars, binoculars, and yellowed biographies to the dinner table, and whatever our conversation topic, they had some trivia to toss us, or excused themselves and consulted Britannica. They were brilliant and conversational; still, I chose favorites–Anne Fadiman’s At Large and At Small, David Foster Wallace‘s “David Lynch Keeps His Head,” Gay Talese‘s “New York is a City of Things Unnoticed,” and John McPhee‘s “The Search for Marvin Gardens.”

Halfway through dinner, in flowed your niece, the Lyric Essay, with emerald rings on her fingers and hair down to her waist. I loved Lia Purpura‘s “Glaciology,” John D’Agata‘s “Notes Toward the Making of a Whole Human Being,” and Albert Goldbarth‘s “After Yitzl.” After dinner, we sat in the guest room and I tried on her rings.

Your relatives were such good company that I forgot about you. And when I turned back to you, I found we’d grown apart.

One day we grabbed coffee and you talked about yourself for hours. At first, I was intrigued. Your tale began with the promise that you’d make it artistic. Or funny. Or that if you talked about yourself long enough, we’d find a scrap or two in common. I left that day thinking what you told me was kind of hollow. Your stories–of an abusive stepfather in Tobias Wolff‘s This Boy’s Life, or an impoverished upbringing in upstate New York in Sonja Livingston‘s Ghostbread–were just about you. They never connected to something larger.

It was like Ander Monson said in Vanishing Point, his book of critical essays:

We can… fault the assumption that individual experience–sans connection to something larger, beauty or social action, for instance–is in itself interesting as a primary subject… Asserting the primacy of the I suggests that we should care about it because it is an I, because it has incurred slights at the hands of others, of the world. And we should care. Sure, I agree with that; everyone is special… and inhabiting their experience allows us to share it, know it… But I still don’t want to read what most people have to say about themselves if it’s just to tell their story. I want it to be art…

You tried to make it art. In Ghostbread, you gave me childhood experiences like a pile of Polaroids. They were beautiful snapshots, but the pile did not make a whole. In the end, it was just fragments of a life–people came and went and never mattered.

And your stories never got to the point where I felt like, “Yes! This is what life feels like.” I believe your stories were true, but they didn’t feel true.

It’s like an anecdote that Stephen King wrote about in The Green Mile. This, at least, is how I remember Steven King’s story. This kid chopped his finger off and then went to a tent revival, a healing service. Church folk prayed over the finger and the finger grew back. And the Green Mile character believed the tale was true because the boy said his finger itched when it grew back. That itch made the difference between credibility and dismissal. These are the details I craved in your pages but did not find.

I always heard John Gardner quoted in creative writing workshops: fiction should be a “vivid and continuous dream.” Memory is vivid but it isn’t continuous. Maybe memory isn’t thick enough for what your pages ask of it–to create wallpapered, furnished dreams the reader can inhabit.

We met again. We drank cafe au lait. I read Dave Eggers‘s A Staggering Work of Heartbreaking Genius, Oliver Sacks‘s Uncle Tungsten, Madeleine L’Engle‘s Two-Part Invention.

You began to win me back.

Dave Eggers disarmed me with his “Rules and suggestions for the enjoyment of this book” and his Acknowledgments section which acknowledged all the book’s conceivable flaws, including “the Self-Aggrandizement as Art Form Aspect.” He did it, proved himself an “I” worth listening to. And he was being so postmodern, so aware of the expectations of the form; this meant that even when Eggers was solipsistic, well, it was a commentary on being solipsistic.

Oliver Sacks stretched your possibilities because he told about his childhood without a trace of solipsism. Maybe this is because he is Oliver Sacks and all parts of the world enchant him. He can’t tell a scientific story without quoting Milton or Auden, much less tell his own story without praising what he was reading or learning from his relatives. The world outside his head is fully and wonderfully present in Uncle Tungsten. Is that something peculiar to Sacks, something not all your legion of writers can manage? I hope not; a single “I” floating solo through life is flimsy.

Ander Monson corroborates:

I can’t see a way to stop… thinking about the I, examining myself… in text and thought. Perhaps the answer… is in research, in listening, in exploring, in taking notes. It’s harder, yes. It’s finding, creating, or uncovering another subject–something else to rely on or parse beyond the self.

Madeleine L’Engle, too, did more than narrate her own experience, and this made you beautiful. Two-part Invention was about her marriage, and marriage exists as something third, not fully one person or the other. Throughout her journal-memoir, L’Engle’s version of first-person was inviting: honest without pedantry and revelatory without narcissism. I felt like I was being offered her experiences, like she was saying, “I want you to know the real me, the way I’d be if you stopped by when my house was a wreck.” This is a generous, self-giving narrator, who humbly gives herself in hope of connection.

Maybe this humility is your greatest possibility.