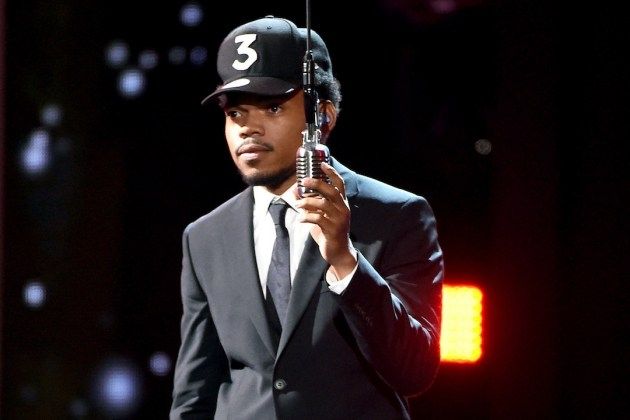

It’s hailed as “Music’s Biggest Night” but in reality, it’s a very, very long afternoon that turns into a glamorous dusk. Outside of the Staples Center, the Los Angeles sun was finally setting. Women wearing millions of dollars worth of jewels, men in custom-tailored bespoke suits, all of them intoxicated by their own beauty and the world’s best champagne, turned their eyes to the stage for one of the final performances.

A song begins, and a female voice belts out from the darkness. The tune is familiar to many in the audience and those watching at home. The rich, pitch-perfect vibrato grows in strength as it continues singing in the distinct and unmistakable style of down-home, Sunday-go-to-meeting worship. A spotlight clicks on, and a slender, impossibly young-looking man dressed in a tribal patterned sweatshirt and jeans appears. He looks humbled, honored to be here but also steady, self-assured. His body rocks with energy as he directs his fingers upward. Pre-recorded vocals cascade out from the speakers, an authority speaking from above. Scoffing at, obliterating the vanity of all those who sit before the stage, the voice speaks with a smirking, palpable sense of irony: “God is better than the world’s best thing.”

And then Chance starts rapping, with the speed and intensity of a seasoned professional performer; with all of the ambition and revelation of a prophet before his king.

That was how much of the country met Chance the Rapper. It was the perfect introduction.

…

Chance’s medley stands in contrast with the performance of A Tribe Called Quest during that same awards show, just moments earlier. ATCQ chose pointed satire and polarizing, hyperbolic statements to accompany their songs, memorably referring to our current president as “Agent Orange” and inviting a parade of hijab-clad dancers on stage alongside them. While it’s demonstrable that this particular brand of criticism greatly aggrieves the White House’s occupant (source: Twitter. His own.), there’s also proof that political satire rarely motivates change within societies. In Heather LaMarre’s study, “The Irony of Satire,” she brings to light the connection between confirmation bias and performances like ATCQ’s and recent Saturday Night Live sketches; these acts of theater leave just enough ambiguity that viewers can absorb what they want to absorb, find amusement in what they agree with, and leave the rest for someone else to interpret.

But Chance’s national debut didn’t abandon politics, and neither does Chance himself. A strong proponent of the successful “My Brother’s Keeper” mentorship program, Chance also led voter-registration drives at his concerts and championed the democratic process throughout election season last year. Chance’s lyrics incorporate political references that sincerely question systemic marginalization and tend to reference role models, not enemies. The only antagonist Chance seems threatened by is Satan himself.

There’s been some commentary that “joy is an act of resistance.” Watching Chance brings us to the inverse question, “Can resistance itself be an act… of joy?”

In the Byzantine Empire, the long-suffering peasants supported a government-sponsored campaign of iconoclasm. They sought out and destroyed religious and political iconography, which they had come to see as symbols not of faith and prosperity but as representations of class barriers and bloodshed. They saw destruction as the only way forward for themselves. Destruction of artifacts has been an oft-repeated sign of resistance and a society in tumult ever since.

Part of what makes Chance so special, so significant to the moment we are in is this: while many seek to deconstruct the broken systems of our divided political classes, Chance remains a true egalitarian. He’s an iconoclast that doesn’t seek to behead the ancient statues of our shared past. He embraces religious symbolism, treasuring them, all the while his very existence desecrates the system he’s escaped. “The people’s champ must be everything the people can’t be,” he declares in the reprise of his song, “Blessings.” In that same song, he remarks that it “seems like blessings keep falling in [my] lap.” He sees his seemingly magical avoidance from the snare of the music industry bureaucracy not as a conquest of war, but a charming accident.

Chancelor Bennett still owns the rights to all of his original recordings. In his own words, he’s “In his own words: “pre-currency, post-language, anti-label, pro-famous.” He’s such a successful streaming-only artist without label representation that the Grammy’s literally rewrote their own rules so he’d qualify to win one. The natural outcome of Chance’s forever free, forever thankful way of thinking is an infectious magnetism that would be impossible to duplicate.

Whether it’s rooting for the Chicago Cubs in the World Series despite his lifelong White Sox affinity, or working to get tickets back from scalpers so that more fans can attend his sold-out shows, Chance inhabits his own charisma with an earth-bound humility that only serves to enchant his audience even further. Chance celebrates without being self-congratulatory, and elevates others with a graciousness that reads as ever-authentic. His lyrics speak to a running interior monologue; one that reflects an awareness, a deprecation, an amusement; but never an ego.

Conservatives will say that our culture has been pulled apart, thread by thread, and that the center cannot hold our country together anymore. Liberals will say that there’s no common ground to stand on when the other side of the aisle has abandoned intellectual honesty in favor of populism. Both positions would indicate that there is no hope, no way forward, no way to delight in each other across the boundaries of race, religion, and politics. Chance proves these people wrong just by existing. If there was no hope left for our shared culture in the Trump era, hope couldn’t have resonated in the Staples Center late on Sunday night. If we were all out of hope, how could hope have brought the house down?

Anger points to anarchy. Satire stares back at us in the mirror. But hope points us toward each other.