I married into a dysfunctional family. My own tribe has their problems, naturally; but I was raised in a pack of females—strong, emotional, spiritual, and confident that our bonds and good hearts would carry us through the world. So when I met my new family, the ones who had somehow produced the world’s kindest, whimsical, resilient, bearded boy I had ever met, I was surprised. They were closed and guarded. I whirled into the family, confident that I would be anyone’s dream daughter-in-law. I let my heart roll out of my mouth with every sentence. And when I received, in turn, scorn and dismissal, I was shocked into silence.

And silence turned out to be the end game, as it is for so many families where abuse happens. Secrets abound even in the best-intentioned: this is what Christ promised to us, that there would always be darkness within. The only cure, of course, is the light—the continually dragging out into the open those things we almost unconsciously bury. The floorboards need to be pried up. The stink and decay of the rot inside of ourselves, the secrets we have hid, are bleached clean. We become like white bones before the Lord, and then, only then, can the flesh miraculously be restored. I knew this, even then. But for awhile, I was silent.

…

“Tuesday night at Bible Study/We lift our hands and pray over your body/But nothing ever happens.”

When I was young and in Bible college, right before I met my husband, I saw Sufjan Stevens perform for the first time on his Illinois tour. I sat, wide-eyed and rapt, while girls in cheerleader uniforms performed behind the quiet, brown-haired boy who knew that whispers were often more powerful than shouts. I strained to catch his meaning, but nothing stuck. I cried when I heard “Casimir Pulaski Day” because I, like the people in Sufjan’s songs, read my Bible every morning, and journaled dutifully my dull and eager-to-be-right thoughts. In the morning I tried to quiet myself, tried to get right with God. Instead it had become an exercise in proving myself, to repeat what I knew I was supposed to say, to earn points and collect sound theologies, to store up enough of God so I could go out and convince others to give him a try. I was only just starting to realize that this wasn’t what I wanted my life to be. I was growing weary of trying to decide who was right and who was wrong.

…

When I was around my husband’s family I felt constantly off-balance. I did not trust myself, my guts or my words. I was quiet, and therefore good, for many years. But the secrets grew and transformed and reached out to others. Abuse thrives in the dark and the damp and the suffocating allure of momentary peace. As an outsider grafted in, my place was never sure, so I allowed myself to be carried for far too long in the already established patterns. Eventually, for both my husband and I, it became clear we would need to swim away. We were the rats, fleeing a sinking ship; we were the ones ruining the mirage that we were all OK. And as we started to swim with all of our might, my silence turned into something more. It began to turn into anger.

…

The second time I saw Sufjan, it was two months after both my daughter and I almost died in childbirth. It was the first time my husband and I left the house together since that momentous event, our first attempt at sticking a toe back into the normal world. It did not go well. It was the Age of Adz tour, and there was a packed amphitheater of pretty, healthy young people; there were video projections with people dancing in disjointed, jerky ways; there was a lot of neon. I couldn’t stand to look at Sufjan, his tattered costumes, the bedraggled duct-tape wings, the headdresses, the falseness I felt everywhere. I wanted to shake him: just tell me what it all means.

I looked around and thought bitter thoughts. None of these people have ever gone what I had gone through. I almost died! My body had turned on me, had decided the baby inside was a threat, and shut down everything I needed to survive: my liver, my ventricles, my heart. So two months early, our daughter was born into a world which was much too big and advanced for her. I looked around the room at people caught up in the rapture of the bizarre songs, the reverence of the fringe, outsider artists, the mashing of spiritual and secular and the unwell of mind. I thought: sure, celebrate the outsider art all you want. But that is the kind of art which comes from one solitary place, deep within. The thread of commonality among so-called outsider artists is that they never progress. They never change. They just keep producing, until the day they die, the same kind of message. A compulsion without growth. We in the audience, and even those on the stage, all seemed a little confused. Are we celebrating revelation or madness? Do we want to be in love with our own sense of righteousness?

…

The ship continued to go down, but it went slower than I would have liked. We watched from afar, and I would have liked to see it wrecked upon the rocks of life; I would have liked to see it splinter and burn, the book of Revelation come to life. I would have liked a little justice. My husband, now a counselor, listens to other people as they talk about their horrific pasts. He listens to the sick and the sad and the oppressed of the world. He operates in an alternate America, where pains are named and laments are voiced, where the Christ we studied for so many years is living. We found Christ, we found him, and we cannot let him go. When we go back to the places we were told he would always be we find nothing but silence; after all, he said he never came for those who thought they were well.

…

My daughter was three, safely tucked into bed with a babysitter, when we went to see the Christmas show. It was beautiful and chaotic, it was an absolute mess of the holy and commercialized. Sufjan’s dad was in the audience. He was older, gray-haired, and waved when Sufjan dedicated a song to him. My husband and I sang along to every word, every song. We sang of jingle bells and hymns older than our souls and it all felt like it meant something. Everyone around us was still young and beautiful and they all had drinks in their hand. But I did not judge them for it anymore. We celebrated everything, and underneath it all our hearts ached. The light had come into the world, and the darkness had not overcome it. But why does the darkness so outnumber the light?

…

I waken in the middle of the night. God is talking to me. God asks me if I am ready to forgive. I tell him I am not, and roll over to go back to sleep. But a small part of me is pleased. Pleased that he would even ask.

Our Christmas with my husband’s family was spent at a discount Chinese restaurant, presents exchanged across a large round table filled with soy sauce and cheap wooden chopsticks. Conversation was stilted, hyperaware. My daughter opened her gifts and in her wide-open way flirted and chatted up these people who obviously wanted her to like them. A few blunt conversations were had; a thick, controlling silence was employed. We drove away from the restaurant and felt we could breathe again. It was all so depressing, but it was closer to the truth. It felt good, in that way.

Sometimes I still read my Bible in the mornings. The Scriptures no longer tell me how to live right, how to be right. They tell me how to be unwell. They tell me that my own lack of forgiveness is a sin, a dark animal clawing up my mind, producing the same art in my life day after day. Now I am old enough and broken enough to see it—but what comes next? In the middle of the night, I hear it. Are you ready to forgive? But I can’t, not yet, because to forgive would mean that the silence wins.

…

“I forgive you, mother, I can hear you/And I long to be near you/But every road leads to an end/Yes, every road leads to an end.“

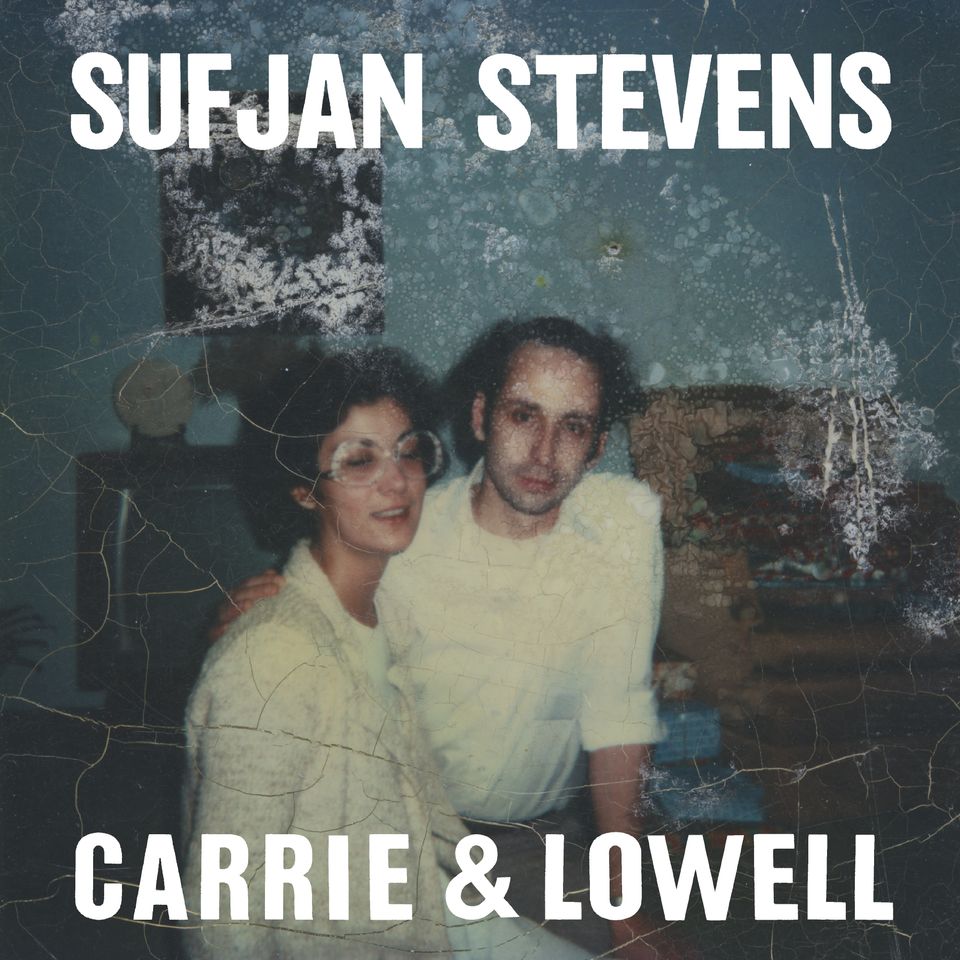

I listen to Carrie & Lowell, Sufjan’s latest album, with tears in my eyes. Reckoning with forgiveness, it is laid bare before me. Everything has already happened; the unbearable weight of acknowledging is already here. The only thing left to do is give up on myself as high priest and high judge. Everyone who ever hurt us, shamed us, abused us, could be dead for thirty years and not know the sting of bitterness we still carry in our hearts. We forgive for ourselves. We face how unwell we have become, and we realize we might want to move on. There are other themes to explore in this life, other dimensions to add to our understanding of ourselves, our families, of God. Sufjan sings about his mother, he goes back to his guitar and his whispered voice makes us all lean in closer.

Maybe every time he plays he will get closer, closer to doing what Jesus asked of us, the most unimaginable thing of all. Maybe Sufjan will continue to feel forgiven as well, as his own fingers strum and pluck and eventually lose their grip on all the hurt that was done to him, his mother dead and buried, her sins still alive and well.