Last month my grandmother died. I knew I’d someday have to say these words out loud, but, nonetheless, I wasn’t ready to say them. Maybe because she helped raise me, and I saw her more like my mom than a grandma—she’d always say “yo soy dos veces tu madre”—or maybe because for the last year, I dedicated myself to caring for her full time.

How am I supposed to lose someone I love so much when I’m still afraid of the dark and of getting up in the middle of the night?

I think a lot about the word strength. What it means. How to become it. And if one day my granddaughter will sit in an ICU chair and think I’m its definition— like I did with my grandmother.

I saw bruises all over her arms, to the point where there was more bruised skin than anything else. To the point where phlebotomists would have to stick, stick, and stick again to find one usable vein. I saw her endure dialysis, surgeries, radiation, and I thought, “God, I will never be as strong as she is. Please do not make me sick like she is.”

But now, instead, I ask God to make me strong like she was. So now when my family tells me I have her carácter, I won’t be so offended. I’ll take el carácter of someone strong any day.

I’m supposed to be really good with words, but I don’t think there are words to describe how truly extraordinary my grandma was. She wasn’t just my grandma, she was also my friend. Someone I could share my secrets with, who would give me advice, who would sing with me in the car, who would make me laugh with the jokes she told.

Her death meant looking through 2,000 old photos of her smiling, laughing, singing—and then I come across one of my grandma, grandpa and me when I was two years old. I’m sitting in my grandma’s lap with my cheeks squeezed between their two faces. We’re all smiling and I thought, “That little girl was so loved.”

What a beautiful gift it was to be loved by her. And what a beautiful gift to have loved her.

The day she passed, my cousin told my mom and me that we had given her a beautiful life, but the truth is she gave me a beautiful life. A life full of jokes and silliness and happiness even in difficult moments.

The palliative care nurse at the hospital where she spent her last few weeks brought to my mom and me a butterfly to release a few hours before she died. As my mom and I made our way downstairs I thought maybe I’d feel something inside me let her go. But it was so anticlimactic for me, and how I wish I had felt something, like my mom did, as I watched the monarch leave its plastic home. I realized later there were two other cocoons in the plastic aquarium the nurse gave us. There has to be a metaphor about life and death in there somewhere, but I don’t have the brain to figure it out right now.

The night before my grandma died, a hundred things went wrong. It wasn’t her multiple organ failure or the thought of losing a woman who had raised me that broke me; it was the hole I found in my favorite sock as I was folding laundry.

Her passing taught me that no matter how much you do for someone while they’re alive, it never quite feels like enough for someone who gave you so much. As a child, and even after I returned full-grown from college, she’d tell me, “Quisiera que ni el aire te tocará,” and I wanted to tell her the same every time I looked over at her.

Yet I still have my grandmother, in the beautiful music I get to call the legacy she left me. My memories of my grandmother aren’t the last few months of her decline, but the music my grandparents listened to and the way I’d see them dance to La Sonora Santanera. She gave me the value of our language and our customs.

In the weeks since she passed, I’ve noticed the need I have for her in my life. Small things like the fact that I never asked where I’m meant to place hot lemons on my neck to get over a sore throat, since she always placed them for me. That though I’ve heard her stories a million times I’m sure there’s one, or more, I won’t be able to remember. That, simply, there are so many little things about her I’m not ready to forget. Maybe this is what death and grief and loss are about: Realizing there is a hole in your chest that can no longer be filled because the person who made your life so whole is no longer here.

When the whole Southern California coast shook, I was sitting next to her in the hospital and I willed it to swallow me whole. Her presence in that time was like a final lesson for me. She often said to me that when she passed, “no quiero que me lloren,” for she would be in glory. I know my hope is in a God who is good, and I take comfort in knowing I will see her again.

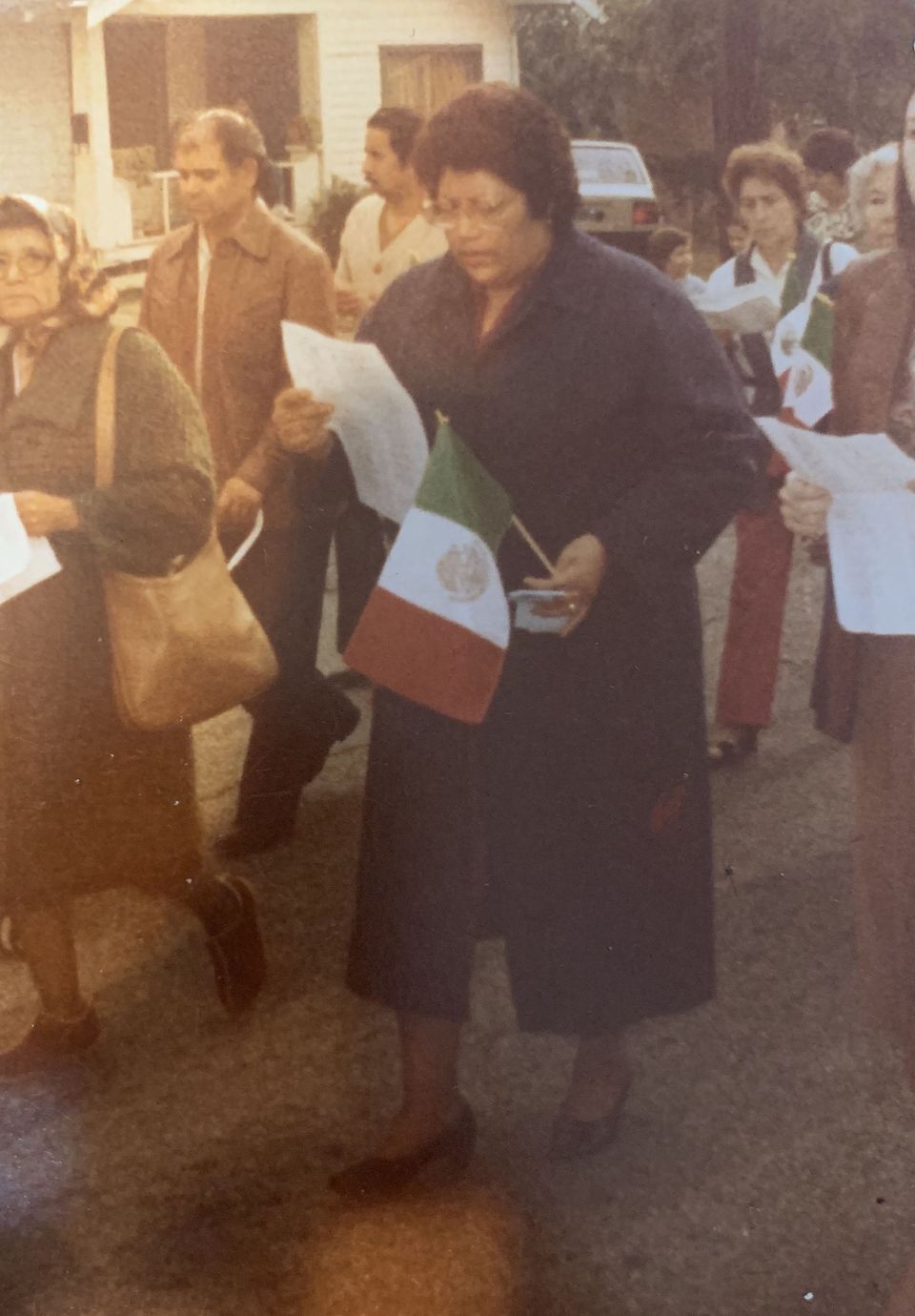

In those piles of photos my grandmother kept, I came across one that made me realize how truly alike we are. There she is, at a march in the ’80s, grabbing onto a Mexican flag. I thought back to the marches I’ve attended and realized she was the only of my relatives who never questioned why I made signs and went to protests or told me it was dangerous or unproductive. Instead, she encouraged me to step up and be loud about what I felt was right. I didn’t have to explain to her what righteous anger meant.

I really do take comfort in knowing I’ll see her again. And while it’s not the same as before, I see her now, still, in that snapshot, standing up for her beliefs; in her words of encouragement to me, spoken in her native tongue; in all those things I can and will remember.