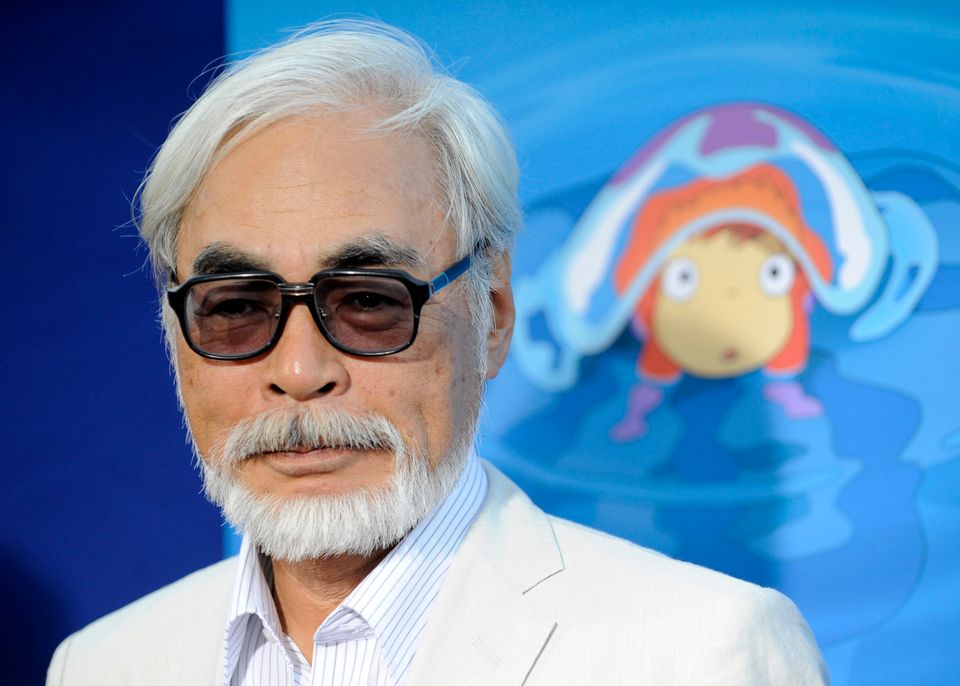

Hayao Miyazaki’s films are some of the most charming in the short history of cinema. The heroes of his animated tales—Pazu in Castle in the Sky, Ashitaka in Princess Mononoke, and Princess Nausicaä in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind—adventure through richly imagined worlds, amongst spirits and gods, where the stakes are very high: love is tested by hate, good by evil, life by death. And despite their many obstacles and inner temptations, Miyazaki’s heroes choose rightly: Pazu embraces love, Ashitaka stands with good, and Nausicaä dies for life.

Through their triumphs, Miyazaki’s heroes are liberated. They soar—literally. All but two of his ten written and directed films feature an extended scene in which our heroes take flight, weave through the clouds, and ride the wind across a lush acrylic sky. One feels free when watching his films.

But Miyazaki himself is weighed down, overburdened and in despair. That’s the principal lesson of Turning Point: 1997-2008, a collection of translated interviews, public statements, essays, and panels on which Miyazaki sat, compiled from the years he directed Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away, and Howl’s Moving Castle. The book offers “lessons” rather than “themes,” because there is a distinct lack of about-ness to it. Miyazaki’s public voice, chronologically ordered, roams to and fro and very far from his films. Even at events convened to explore them, he moves quickly to other subjects, often timely matters of public concern, and those subjects slide to talk of Japan’s cultural troubles. Eleven years of free-roaming conversation will reveal the bent of a man’s thoughts; the conversations collected in Turning Point capture Miyazaki deflecting talk of his films and hurrying to speak of Japan’s imminent demise.

Dimming the Children

While the troubles named are many, for Miyazaki, the greatest threat to Japan’s future is the systemic dulling of Japanese children. Their fate, Miyazaki avers, is to be made into “normal, boring adults.” But he means far more than “boring.” He fears Japanese children are dimmed by a culture of overconsumption, overprotection, utilitarian education, careerism, techno-industrialism, and a secularism that is swallowing Japan’s native animism. The play, imagination, and moral formation of children have been ceded to the sedations of digital gadgetry and—surprisingly, in light of his own profession—animation. Japanese children are formed in the womb of technology, says Miyazaki, and raised on the easy pleasures of Japanese comics and animated films:

“I’m part of a subculture that makes animated films. What we have done is to narrow down the world of children and fill that narrow sliver with this subculture. The television stays on all day long even in rural homes [just as in urban homes]. People’s lives have become filled with this subculture.

“This,” he adds, “is the source of the downfall of a people.” This is not hyperbole; seventy pages earlier, Miyazaki lamented that manga—Japanese comic books and graphic novels—have become the “common denominator” of the Japanese people. This is “the peril faced by Japanese culture.”

Downfall at the hands of cartoons and television seems alarmist, curmudgeonly, and, in light of Miyazaki’s own profession, self-centered. However strange this may be, on one point he is surely, but sadly, right: Japan is in peril. Indeed, it’s dying. In its 2013 survey of the sexual habits of Japanese, the Japan Family Planning Association (JFPA) discovered that a catastrophic number of Japanese teens and young adults, aged 16-24, have lost the desire for sex. A quarter of Japanese young men were “not interested in or despised sexual contact”; 45 percent of women reported the same. Not surprisingly, in 2012, fewer Japanese babies were born than in any other recorded year. The consequences are clear: JFPA director Dr. Kunio Kitamura warns that Japan will “perish into extinction.”

A Crisis of Desire

Japan’s crisis is perplexing. Countless explanations have been put forward—mostly economic, many social, none which fully satisfy. All agree, however, that “hopelessness” has extinguished the erotic drive of many young Japanese. The root of this hopelessness, observers frequently assert, is ongoing economic stagnation. Miyazaki does not address the erotic conditions of young Japanese directly in Turning Point, but he concerns himself with Japan’s interior life time and again, especially with how the imagery of Japanese pop culture and technological gadgets affects desire and disaffects Japanese from the world and one another. Where Miyazaki parts from his contemporaries is that his exploration does not give economics pride of place, even though he treats it with great seriousness. For Miyazaki, despite the 25 years of economic decline, the “critical” issue Japanese face is their passionate need of the synthetic and digital. This, he says, “is a bigger problem than all the economic chaos.”

According to Miyazaki, Japanese children lack a taste for the real and human and know little of the natural beauties of the world. He said:

“This was fated from the time when television, or manga, or video games, or even photo print clubs came to fill in something children had lost [a less restricted life, close to nature in the pre-war economy] and became more exciting than reality.

The desires of many—if not most or even all—Japanese children, Miyazaki believes, have been hollowed, stretched, inflated for the false, and, thus, deflated for the true. The beauty of woman for man and man for woman, especially, has been supplanted by the cartoonish, pornographic, robotic, and monstrous. This is what he meant when he called animated films “the source of the downfall of a people.”

According to Web Japan, a Japanese information website, manga accounts for “36% of the volume of all books and magazines sold in Japan,” an astronomically high share of the market. And their stylings have stretched far into other mediums, deeply influencing even the content of novels, making manga, as Miyazaki put it, “no longer a subculture,” but, rather, “the originator of culture.” In Japan, manga imagery is ubiquitous—advertising, television, social media, toys, public festivals, conventions, and social groups—and travels with you via smart phones, tablets, handheld videogames, and countless other portable gadgets. “Everything,” Miyazaki said, “has become insubstantial and mangalike.”

Hoping for Reality

Miyazaki recounts this to his own great shame. An extraordinary 96 percent of Japanese have seen one of his films. His fear is that he is greatly responsible for the fantasia of Japanese life. His hope, on the other hand, is that his films illuminate what others make dark. Miyazaki’s ambition is to make realist films that urge children toward reality. He, for instance, described his film Spirited Away—about a ten-year-old Japanese girl, whose quest is to land a job from a witch who owns a bathhouse for tired spirits—as an attempt to “trace the reality in which ten-year-old girls live.” But with all the frog people, sentient soot, and ten-foot babies, what could such a reality be?

Much as it appears. Miyazaki is an animistic pagan living among a world of spiritual essences—beasts, insects, plants, trees, rocks, and the wind are ensouled—where the forest groves and deep waters are home to the gods. At least, that’s how he styles himself.

His animism may explain the content of his films, but not necessarily his approach to film craft. His criticisms of Japanese culture and the manga industry offer a better starting point. The largest problem facing the manga industry is that the people running it are anime fanatics, known as otaku in Japan. These “sickly otaku types,” as Miyazaki called them, were reared on manga and Japanimation, and developed an inordinate desire for them—their shape, scale, motion, symbols, and narrative tropes. Such children, “locked in [manga’s] own enclosed world,” became illustrators themselves, reinforcing the enclosure. With their arrival in the industry, characters became boxier, eyes ballooned, and, to be frank, breasts grew larger. The expressiveness of the manga industry was further attenuated, a cycle that cheapens and thins the general taste of Japanese society. These otaku, “raised amidst the clamor,” Miyazaki said, “probably can’t be the flag bearers for new images.”

Bearing New Images

To bear “new images,” to make films that liberate, the filmmaker must himself be liberated, free of the customs of the genre. That’s why Miyazaki frequently stresses that he does not “watch film at all” and describes his own career as an ongoing effort to escape the yoke of his great forebear, Osamu Tezuka, the father of manga, creator of Astro Boy, and Miyazaki’s greatest influence. That’s also why he strongly urges that, if an illustrator is to spur audiences to seek and love the world, he must himself be filled with its riches. That is, he must gain an intelligent understanding of it by cultivating “a constant interest in customs, history, architecture, and all sorts of things.” Otherwise, he “can’t direct.” And if he doesn’t have time to study, he must “look carefully at what is right in front of [him].” If he fails to do so, no matter what he makes, “it turns out to be a film we’ve seen somewhere, or something we’ve seen in manga.”

That’s also why he strongly urges that, if an illustrator is to spur audiences to seek and love the world, he must himself be filled with its riches.

Unlike most of today’s major directors, there is nothing counterfeit about Miyazaki’s work. His films have an inner clarity and beauty that few others achieve. Yet they are frequently wrapped in mystery, ambiguity, and confusion. And purposely so. Miyazaki not only fills his films with the treasures of intellectual study, he also refuses to over-clarify them. As he said of his epic Princess Mononoke, “I made this film fully realizing that it was complex…If one depicts the world so that it can be figured out or understood, the world becomes small and shabby.” To truly mirror the world, he makes his films difficult to understand, because “there are so many things in the world that we don’t understand.” If a film answers all the questions it raises, after all, one need not search beyond it. Miyazaki’s films stretch into the world and require things of it for their completion, say, a conversation with friends, a hike through the woods, a fear of the gods, or even a childlike innocence.

“If one depicts the world so that it can be figured out or understood, the world becomes small and shabby.”

When reading Turning Point, the burden of synthesis lies with the reader. For that reason, despite its evident charms, I cannot recommend it, except to would-be biographers or critics. As much as one can glean from the book about Miyazaki’s craft (and much more can be mined from it than I have), his thoughts move most naturally towards Japan. That, the book makes clear, is where his heart is—and not with his films. This, paradoxically, is one of the keys to their greatness. His films are not about his ego or even the art of film. They climb for far higher reaches.

What becomes of Japan, only time will tell. But I hope along with Miyazaki that his films do spur Japanese children to seek a better, realer happiness. As Miyazaki said, “All I can do is to create films that help children feel glad they have been born.” That is all his films ever do. And that is no small thing.