Art used to be part of my life.

When I was single, I often visited museums and galleries, special exhibits and art festivals. Recently, though, I married for the first time at age 42 and became a step-mother to three sons. I realized I hadn’t been to a museum or an art gallery since the wedding. In fact, I hadn’t been since we were engaged.

“Would you be interested—or at least willing—to go to the art museum with me on Saturday?” I asked my husband during a particularly rough week. When he agreed, I was relieved. I knew I needed the presence of art in my life. My husband knew it, too. The next day he told me that an arts and crafts fair that I had been to and enjoyed in the past was also going on in a nearby town on that Saturday.

The only problem was that we didn’t have time to do both. Would my craving for art be best satisfied at a museum or a fair?

“All of culture . . . is a struggle over how we should imagine our lives,” writes essayist Scott Russell Sanders in “Letter to a Reader.” Would choosing the museum over the fair be the equivalent of saying that Monet imagines life better than the woman who designs jewelry or the soap maker whose offerings at last year’s fair kept me clean for months? I was torn.

I face this dilemma between “high culture” and “low culture” (or pop culture) regularly: should I read Thomas Hardy or my friends’ latest blog posts? Should I eat at the chef-owned R Bistro or the Pita Pit? Should I go to the symphony or listen to the folk singer at a nearby coffee shop?

In a February 2013 Guardian article titled, “High culture versus pop culture: which is best for engaging students?” Andrew Jones, head of religious studies and sociology at a community school in Hertfordshire, discusses the effects of introducing both types of culture to students in educational environments.

While exposure to high culture might help students “develop an appreciation of the finer things in life, such as poetry and classical music,” Jones also says that popular culture feels more relevant to his students, makes the subjects “alive.” Often, he combines both: “My colleagues and I have planned lessons on heaven and hell that mixed clips from Tom and Jerry with Gustave Doré‘s illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Furthermore, lessons on suffering include the literature from Elie Wiesel and the paintings of Francisco Goya.”

Maybe I should have tried harder to squeeze in both the museum and the fair? Or is choosing between them, beyond a mere scheduling conflict, really being honest about the nature of art?

In his 2013 commencement speech for New York’s School of Visual Arts, cultural critic and prolific author, Greil Marcus, refuted the notion that high and low art should really be separated.

I’ve always believed that the divisions between high art and low art, between high culture, which really ought to be called “sanctified culture,” and what’s sometimes called popular culture, but really ought to be called “everyday culture” — the culture of anyone’s everyday life, the music I listen to, the movies you see, the advertisements that infuriate us and that sometimes we find so thrilling, so moving — I’ve always believed that these divisions are false. And, as a result of trying to make that argument over the years, I’ve also come to believe that these divisions are permanent — they can be denied, but they can never go away.

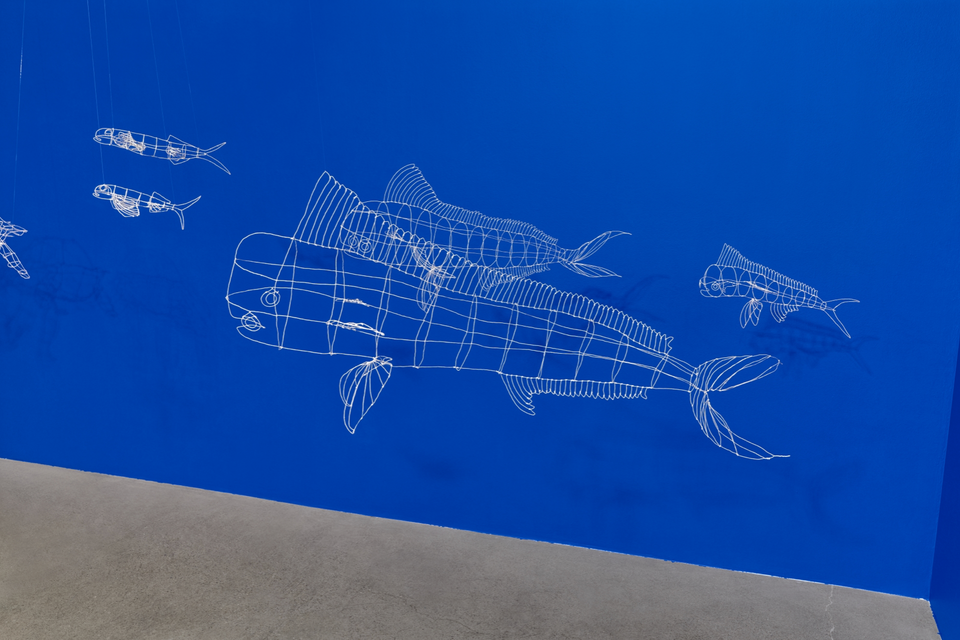

One particular temptation for choosing the museum over the arts and crafts fair that Saturday was a special exhibit of Chinese artist and cultural protestor, Ai Weiwei, whose work could leave Beijing while he himself was detained and surveilled on a daily basis. While museums of high culture regularly exhibit his work, I did wonder as we walked throughout the gallery (yes, we chose the museum), what makes his photographs or his sculptures “sanctified,” as it were.

I left the museum that day feeling different than usual. Truly, I had seen life as Ai Weiwei imagined it. But it left me wondering how to imagine my own life. “Beauty” didn’t describe what I had seen. But was it was a revelation. Was that enough to call it art? Marcus says “yes.”

That’s what art does, that’s what it’s for—to show you that what you think can be erased, cancelled, turned on its head by something you weren’t prepared for—by a work, by a play, a song, a scene in a movie, a painting, a collage, a cartoon, an advertisement—something that has the power that reaches you far more strongly than it reaches the person standing next to you, or even anyone else on Earth—art that produces a revelation that you might not be able to explain or pass on to anyone else, a revolution that you desperately try to share in your own words, in your own work.

And even as I nod in agreement, I wonder if the opposite would have been true at the art fair? Sure, I would have seen lots of pretty things, some even beautiful. I know; I’ve been to the fair before. But I don’t recall any revelations. Where does that leave the soap maker?

Perhaps this is the urge that Marcus so deeply regrets about the division of high art and low art. When one person or party or nation says you must see “this” as beautiful, or only “that” can provide you with a revelation, Marcus calls it an “urge to fascism,” a dangerous word when applied to people in power. But perhaps still an ugly word when applied to individuals passing judgment over each other’s imaginings of life?

It all comes down to that urge to fascism—maybe a big word to use for art, but I think the right word—it comes down to that urge to fascism to know what’s best for people, to know that some people are of the best and some people are of the worst; the urge to separate the good from the bad and to praise oneself; to decide what covers on what books people ought to read, what songs people ought to be moved by, what art they ought to make, an urge that makes art into a set of laws that take away your freedom rather than a kind of activity that creates freedom or reveals it. It all comes down to the notion that, in the end, there is a social explanation for art, which is to say an explanation of what kind of art you should be ashamed of and what kind of art you should be proud of. It’s the reduction of the mystery of art, where it comes from, where it goes…

This issue of shame came back around to us a few weeks later when my husband and I again chose a visit to the art museum, this time bringing our boys along. We wanted them to see Ai Weiwei’s work, to experience the same revelations we had. But those photos and sculptures that had moved us earlier now required justification. “It’s a statement of protest,” I explained to our youngest son who giggled at the photo of Ai holding up his middle finger to the White House. “They gave him a concussion when they were arresting him,” I said about the MRI image of Ai’s own brain. And I felt myself flush when we saw the picture of a naked man suspended from the ceiling in chains.

And we didn’t even risk taking them to the Matisse exhibit a few months later where we knew the Odalisk drawings and paintings would be far more than their young minds could sort through at this stage. Not to mention our own Midwestern adult sensibilities. Fascism? Perhaps. Or maybe just practical parenting. But why, then, do we “protect” the boys from Matisse while regularly exposing them to the advertisements of cable television or the magazine covers in the check out lane at the local Wal-Mart? And what about Robert Indiana’s 8-foot-tall polychrome Numbers made me so proud as I drug the boys through the rain to the outside patio at the museum that day, insisting that they were going to love them? (They did love them, by the way. But maybe only for my benefit? Maybe only because I had insisted?)

High art and low art may indeed forever be separated, and in earnest, many, like the educator, Andrew Jones, will try to bring them back together, to find a happy balance.

My life attempts to inhabit such a union. I find a greater negotiation, however, from Madeleine L’Engle, whose everyday encounters with high art not only reduced their mystique, but made her own creation of low art irresistible. From A Circle of Quiet, she writes:

I wrote poems, too. Looking through some old journals, I came across several. There was one, notable for its arrogance, if nothing else.

We lived on 82nd Street and the Metropolitan Museum was my short cut to Central Park. I wrote:

I go into the museum

and look at all the pictures on the walls.

Instead of feeling my own insignificance

I want to go straight home and paint.

A great painting, or symphony, or play, doesn’t diminish us, but enlarges us, and we, too, want to make our own cry of affirmation to the power of creation behind the universe. This surge of creativity has nothing to do with competition, or degree of talent. When I hear a superb pianist, I can’t wait to get to my own piano, and I play about as well now as I did when I was ten. A great novel, rather than discouraging me, simply makes me want to write. This response on the part of any artist is the need to make incarnate the new awareness we have been granted through the genius of someone else. (L’Engle 147)

So yes, we went to the museum. We even became members that day, my husband and I. It was his idea, actually. And not because we value high culture more than low culture, but because we very much want to be inspired to create our own art to imagine our lives as something more than they currently are.