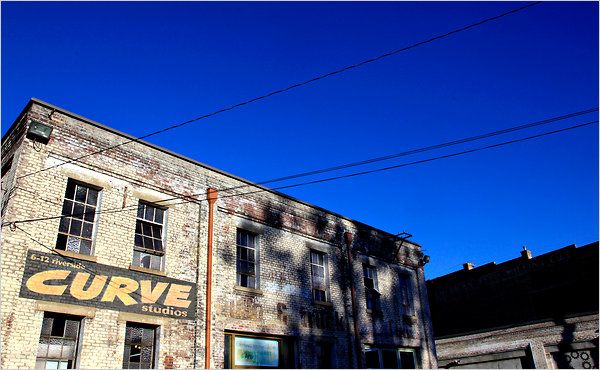

Recently my girlfriend and I went to the river arts district in Asheville, NC. The final brewery we wanted to visit was closed, so we turned to art. Mostly empty, one of the buildings was a mixture of studios and galleries. We looked at pottery, asked the artists some questions, and descended into the basement gallery. The gallery rested in a repurposed fall-out shelter—the modern equivalent of the Neolithic cave. It was primal, dank, providing a sense that we were not the only living things present. As we entered, a teddy-bear-esque humanoid hanging by a noose greeted us. The first painting held former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke celebrating with the CEOs of Goldman Sachs, Wells Fargo, and my own Bank of America in some palatial hall. Their eyes were cowish—wide and wet—with clawed hands holding bursting bags of cash. In another psychedelic painting machine-guns emerged from politicians’ mouths spraying bullets and a set of otherwise traditional portraits featured drones zooming overhead. Grenades with locks rested atop display stands and a large oil painting of a wild-eyed child eating dog food hung in the corner. There was also a half empty bottle of wine and a glass with a broken stem, but this was not part of the official display.

These pieces attempted to pry open the face of our political clockwork and unveil the gears of greed and avarice pumping and steaming underneath. Here was the full fury of didactic, pedantic, finger-wagging art. At the very least it sought to incite a response, a visceral reaction. If Ben Bernanke sleeps the sleep of the just, maybe I should toss and turn with the restlessness of truth. And while I agree with what those fingers were wagging at, I hated this art. In this repurposed fall-out shelter, political commentary became its own form of kitsch.[1] Any level of complexity or variation in mood would have suffocated this art’s explicit message and straightforward emotional agenda. Through political argumentation these pieces covered up the humanity of others, each brush stroke composed of equal parts paint and op-ed. Overall, my dislike of it boiled down to a cliché; we stood amidst art that was all telling and no showing. Like mimes on their day off, the pieces just wouldn’t shut up. Am I unfair? No doubt.

Uncharitable interpretations have a way of generating more questions than answers. This one raises the expected question; how does one define art, especially good art? I’ve been told good art is, and is for, many things: self-expression; making the world strange; becoming a better person; transcendence; a conduit for the sublime; beauty; the infinite; justice; catharsis; instruction; entertainment; life; death; power; love; truth; gift; story; meaning; excess of meaning; exodus from reality; forming the slow speed of empathy; aristocratic self-aggrandizement; art is useful, art is useless; art is art, art gives us, us; art is a mirror; art is spectacles; art is a window; an axe to break up the frozen sea within us; art is dead.

If it’s dead, can I poke at it with a stick?

For me good art is an image, song, sentence or structure that causes me to read, look, or listen at least twice. There are many reasons that I’ve engaged something twice. Sometimes it’s because I enjoyed it or because my teacher assigned it or because I disagreed with it or because my church reveres it. However, I tend to return to a work of art because it contains some subtlety or provides pleasure. I felt love or meaning, and my senses invited me to “spend a little more time.” I return to the work with a reason, asking “How much of the world is it showing me?” or just wanting to experience it again. The art and I strike up a relationship, sometimes even a friendship.

Oddly enough, for all of the time I spend with it, (esp. novels and film) art has played a humble role in my life. If I ever find myself at a psychological precipice, I doubt art will be the one to talk me down.[2] This is a boring confession, but art has never saved my life. What would that even mean, how would that happen? There I am, my heart flat-lining with despair or anguish and Samuel Beckett runs in, gives me CPR, and restarts its pumping? This is not to make light of these things. Art has saved people, just not me.

Even though art hasn’t “saved” me, amidst its twiceness art has changed me, formed me, even seduced me. I read Ender’s Game over and over because I want to make sure I’m nothing like the Napoleonic protagonist, Ender. I read Gilead over and over because my idea of grace needs to be sanctified, stripped down to the essentials. I watch Life of Brian because I want to laugh. I pray the Psalms because they give language to my grief. I see the Broadway production of Lion King over and over because my sister wants to. With others, I kneel before the cross because it stands as sign that God “takes the existence of suffering seriously.”[3] My twiceness hopefully relates to acts of repetition residing in the creation of the art. The photographer snaps one more picture for the love of it, the dancer jumps back onto floor for the fun of it, the drummer strikes the drum again for the fullness of it, the author writes another draft for the truth of it—each concerned with the good of what they’re making. And I return for different reasons, some good some bad, all of them human—a desirable déjà vu, a willingly Sisyphean act. In each encounter the cup of my senses overflows, spilling into my incomplete perception, mixing measures of love into loneliness, diluting falsity with truth, dissolving small hard bits of ugliness and ignorance.

Return with me to the fall-out shelter—my brain floating in beer amidst this violent art: the drones, the politicians, the grenades, the noosed teddy bear. The drone peels itself off from the portrait, flies to D.C. seeking the destruction of Ben Bernanke’s moneyed bacchanalia. The grenades undo their safety pins; rolling into the nearest bank vault; the teddy bear remains still as ever; the art, an AI becoming self-aware, the human creation decides it doesn’t want humanity anymore. These machines of oil and ink and papier-mâché determine that humanity is the excess, the virus requiring elimination. Each piece longed to turn perpetrators into victims, imitating the violence it sought to critique. This art made people engaged in dehumanizing activities, inhuman—attempting to take away any twiceness for flesh and blood. It elects to make evil free of ambiguity, one-dimensional, the work of individual and indisputable devils.

I’ve heard that survivalists secretly wish for the apocalypse. As we walked around the bunker, these pieces screamed that everyone outside was already dead, already lost, already infected by the plague. The apocalypse was now. The only way to survive was to stay, locked up, never breaching the world again. But this bunker art got the world inside out—inviting us to break out the bubbly at a funeral and bring ashes to a birthday. Each piece is an answer that forgot the question; their vision of survival was actually a form of death. Here, ploughshares were beaten back into swords.

What did I do?

I walked upstairs and bought some pottery.

[1] I imagine this art’s ideal American government is something akin to 1920s Paris ex-pat community. Congress split between the parties of poetry, painting, writing, and music—you walk into the U.S. Capital’s rotunda filled with the in-use painting easels of Senators. The sound of jamming cover bands leaks under the doors of congressional offices. This is just a guess though.

[2] As I say this, a library copy of David Shields’s How Literature Saved my Life, the kindle edition of Gregory Wolfe’s Beauty Will Save The World, and Francis Spufford’s The Child That Books Built are all judging me.

[3] Francis Spufford, Unapologetic: Why, Despite Everything, Christianity can still make Surprising Emotional Sense, 164.