Now hold still, ‘cause this is really going to burn.

Lately I’ve spent some time watching the films of David Gordon Green. If you aren’t familiar with this little known filmmaker, don’t fret. It wasn’t until recently that I discovered him myself. How did I come upon such a little known, “indie” filmmaker as David Gordon Green? The lead singer of Ola Podrida (the band that is single- handedly keeping it real for indie folk), David Wingo, is the soundtrack composer for many of Green’s films. As a fan of Mr. Wingo, it was only a matter of time before I discovered his alternative means of supporting himself. In a word, David Gordon Green is an auteur. Green’s films carry such a unique and indelible mark that his style and, more importantly, tone are impossible to miss. His intimate and serious treatment of material evokes the solemn reverence of a boy unable to look away as he stares at the time-stained remains of a skeleton. Put simply, David Gordon Green makes Southern Gothic films.

Prior to watching Green’s films, my experience with the Southern Gothic genre was composed of collections of short stories about redemption and the grotesque by William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, William Gay, and Cormac McCarthy early in his career. These names are synonymous with the Southern Gothic canon, which for me has always been the dry whiskey of literature: the first taste and swallow undeniably bitter, yet never failing to produce lasting, powerful effects. The same holds true with Green’s cinematic Southern Gothic. When sincere attempts to breathe new life into aged genres are rare, it is comforting and refreshing to experience on screen the same Southern Gothic sentiment that is so familiar when written upon a page. That, my friends, is the true mark of a rich genre.

Rule one of tasting Southern Gothic: one cannot forget the bitterness of the swallow, a sensation David Gordon Green’s films linger on. I recently watched Green’s Undertow (2004) and Snow Angels (2007), and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about both.

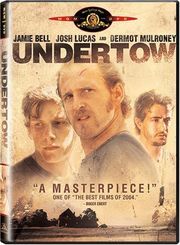

Undertow stars Josh Lucas, Jamie Bell, and Dermot Mulroney as an uncle, his nephew, and brother, respectively, locked in a struggle over a family secret in the hot summer backwoods of Georgia. The film drips with Southern Gothic conventions. You can practically taste the humidity in every shot. The environments that Green conjures up are characters unto themselves: a rundown house in the middle of the woods as the site of a murder, the skeletal ruins of a junkyard, the lazy movements of a passing stream, rain-slick pigs struggling in muddy mire. Film stock, please meet Southern Gothic. Really, Green has nailed it. And his pacing is so subtle, so laid back, that one gets the impression that the characters might not actually ever reach the anticipated conclusion, filling the viewer with apprehension of the reckoning that awaits at the film’s end. David Gordon Green takes his damn sweet time telling this story, and the overall effect of a meandering family tragedy is only strengthened by such patience.

Snow Angels is David Gordon Green’s reminder of the oft-repeated adage that life is pain; suffice it to say, Snow Angels is one of the most sincerely depressing films I’ve ever seen. It makes Requiem for a Dream look like a nice movie about three twenty-somethings living in New York. The film’s overwhelming grimness is at once obtrusive and absorbing, leaving the viewer unable to do anything but pray that things get better for the characters. Spoiler alert: things never get better. Bleak mood aside, Snow Angels is filled with unbelievable performances from Sam Rockwell and Kate Beckinsale. As in Undertow, the actors so fill their characters that it is almost impossible to look away. David Gordon Green evidently excels at getting the very best out of his actors, a trait that seems to be lacking in many contemporary directors. The story digs through the smiles and tears of human relationships, exposing the raw consequences of unfettered affection and untended heartache. David Gordon Green’s film operates in very much the same way as a firing squad. The catharsis of the film’s climax merely serves to reload and give the audience a moment of respite before discharging another salvo of tortured midwinter angst through the film’s wounded characters. Along with this double-barreled emotionalism, Green’s use of environment gives an otherworldly feel to the film, as though the nameless town the characters inhabit is some netherworld trapped in eternal winter, existing in an undertone of a higher power’s omnipotence throughout the story’s unfolding. Ultimately though, Snow Angels’ strongest character is the human heart and Green’s best revelations are the tremors of that heart breaking. Viewer beware, Snow Angels is rough, but then again, the bitterness of the Southern Gothic always gives way to a lingering sense of understanding and poignancy. Snow Angels knocks the air out of your lungs, and you’re not sure if you’ll ever get it all back.

As artistic beings, in the traditional sense of “those who create,” it behooves us all to keep an eye on the work of David Gordon Green. The fusion of a seemingly tired and often overlooked genre as Southern Gothic with the film medium is no easy task, making Green’s personalization of the genre while still keeping a strong grasp on its classic conventions all the more impressive and nostalgia inducing. This guy certainly has a style unto himself, and it is steeped in Southern Gothic whiskey. Sip slowly.