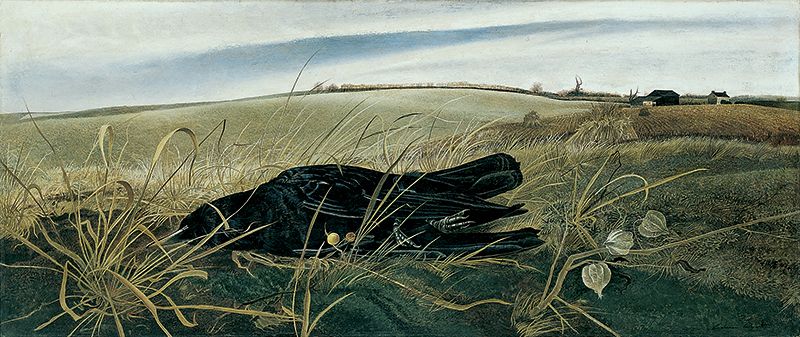

Cover image: “Last Light”, watercolor on paper, 1998 @Greenville County Museum of Art, ©Andrew Wyeth

When I moved out to Colorado from South Carolina, I was embarrassed by my Southern origins. My voice still raised at the wrong inflections, still drew out vowels into two or three syllables. I wanted the sophistication and sleekness of the city, not the cracked feet of my grandmother’s kitchen table surrounded by patterns that died in the 1970s. I wanted a change of scenery. I traded a field of red clay for a vista of cascading mountains.

And then, as I began to be away for longer periods of time, home became this idealized notion. Home was a cool summer evening in the country, with fireflies flitting by that we would catch in Mason jars, as my mother brought out fresh sweet tea with a smile. Then, I would go home, and the humidity would suffocate, the bugs would bite and there was no sweet tea to be found, with all the sounds of nature drowned out by arguing. We didn’t even live in the country anymore; the trees barely hid the encroaching neighborhoods behind us.

A few years ago, on a trip home, my father begged me to go to the local art museum to see an exhibit by his favorite artist. There’s a tradition of amateur painters in my family, one that I was unkindly left out of. My father was taught to paint by my great-aunt. The houses of my family have always been lined by my father’s oil colors, mostly of nature, scenes of places he’s been and seen. I always found it odd that my father was such a talented painter, aside from being an engineer and businessman. I always cherished this secret artistic side of him; it made him much more sensitive to the “aliveness” of the world around him. I think it was that sort of view of the world that he wanted to pass on to me.

I chuckled at the idea of my town having an impressive museum, but his favorite artist was on display, so I trudged along, cursing the humidity as we drove amidst open fields. This was the first time I experienced Andrew Wyeth. I quietly maneuvered among his temperas and watercolors, with my father explaining certain techniques. Wyeth’s concept of home dispelled the idealism and communicated a reality I had forgotten. I wanted to cry right in the middle of the small gallery. My father looked sympathetically at me like he understood and knew that I had grasped the meaning of it.

To this day, he can’t really verbalize how he feels about Andrew Wyeth’s paintings, just that “they feel like home to me.”

The stark contrast of the yellowed land and green growth, light and dark, in Wyeth’s paintings mirrored the dry fields of my childhood, my grandfather’s hands, the decrepit auction house on the side of the road, and the bushes bursting with blackberries behind the train tracks, reminding me that my roots were rugged and dry and tough. But they were real, and that was what mattered. Attachment to reality, tradition, history, the people and places, staying and not running away, seeing the beauty in the ordinary—all these notions fluttered from Wyeth’s paintings into my head, like the lone feather floating amidst a barren field in one of his watercolors. I needed to reconsider home.

What is home and why is an Andrew Wyeth painting the closest I’ve ever gotten to understanding it?

Philosopher James Tuiedo wrote that getting to a philosophical understanding of home requires us to rethink our understanding of safety, fragmentation, and transcendence. At the core of one’s understanding of home is the understanding of identity and self-perception. In our concept of home, we “materialize and territorialize” who we are.

Home is a place where we make dynamic and continuous connections between the past and the present, always reevaluating who we are in light of it. Tuiedo writes:

“Caught in a chiasmic relation of immanence and transcendence, we are assimilated to a dynamic interplay of familiarity and difference, as if we were weaving together threads of nostalgic security and transformative growth.

Ultimately, we understand home through our creative preservation of it.

This sort of creative preservation of home seems to be what Wyeth was getting at. Richard Meryman writes in his biography of Andrew Wyeth that his

“‘truth’ is the essence of objects and people, everlastingly elusive, teasing him forward. He says, ‘I want to get down to the real substance of life itself.’ The route to his goal is realism, because ‘the object is the art, not what I make of it.’

The land itself is the art; the home itself is the art. Perhaps home is the opening of eyes to the present value, rather than what I may construct it to be: the relationships of family members, though sometimes tainted with arguments, yet always abounding in love, and the land that doesn’t ask for much but gives a lot.

How do you understand the land? How do you understand where you live? In Wyeth’s paintings home becomes art. I think this is at the heart of the American Pastoral movement. Not the bucolic, edenic sort of pastoralism that mirrors that of a Thomas Kinkade painting, but a kind that wrestles with the beauty and bone of the land, its hardness and harvest. My problem is not accepting the idyllic beauty of some corners of my home; it’s accepting the yellowed, withering field behind my grandparents’ house that sporadically produced undersized apples and over-ripe berries as a form with value and beauty. It’s accepting the unsavory parts of the cultural heritage I come from. Perhaps that why Wyeth’s paintings stood out to me. The landscapes he painted were dry, hardened, and bare, unyielding from their depiction of a difficult culture, and yet flowing with grace and elegance.

My problem is not accepting the idyllic beauty of some corners of my home; it’s accepting the yellowed, withering field behind my grandparents’ house that sporadically produced undersized apples and over-ripe berries as a form with value and beauty.

Is home merely an escape from fragmentation? Tuiedo suggests that if this is our sensation of home, we will continually be disoriented by the changing circumstances of life that embed themselves within our concept of home. If safety is the key concern, can one feel at home when the circumstances are uncertain? If wholeness is the goal, what shall we do when the cradle of we what consider home is broken?

But what happens when one sentimentalizes home? Tuiedo suggests that we may find homeless in the warmth of the hearth and more in the fire within it, the seed of transformation and change. When you try to escape the wildness of home, you lose the true understanding of what it is. Andrew Wyeth was not a sentimental man. In his biography Andrew Wyeth: A Secret Life, Meryman recounts Wyeth’s disdain toward a painter who painted the sea in fluffy pastels. The sea was supposed to be wild and hard, not comforting. He did not have many attachments to people, as his wife Betsy pointed out, but had deep attachments to the land.

We may find home less in the warmth of the hearth and more in the fire within it, the seed of transformation and change.

Andrew Wyeth painted the hardness of the people and landscape of Cushing, Maine. Christina Olsen, who is the poised woman dragging herself across the ground in Wyeth’s Christina’s World, was a woman of intense pride, who would sooner leave the house as a soiled, stinking mess than bow to weakness.

In Walden, Thoreau urges us to seek out the unfamiliar in the home we have grown accustomed to, to find wonder within it, to embrace the wild as a means of disorienting our complacency in our home. Embracing the arguing and the messy relationships, as well as the hardened land, might bring a new level of transcendence that was missed before. As a family friend, Elizabeth Sargent, remembers about Wyeth,

“Andy was always so interested, gulping in all of life. His mind was open and receiving everything, every impression. You could see his imagination in his eyes – far away. With Andy you feel the earth is always new.

Perhaps we can come to see home as a place of continuous newness, a place that simultaneously subverts and redeems itself.

But, ultimately, I found in Wyeth’s paintings, what is home if it is not some sort of love? There is a love for the ordinary, and the love of roots, rugged as they may be, that draws one towards home. It is this sort of love that American pastoralism and Wyeth are trying to communicate, and it is neither a pretty nor an ephemeral love. As Wyeth himself says, “I think one’s art goes as far and as deep as one’s love goes. I see no reason for painting but that. If I have anything to offer, it is my emotional contact with the place where I live and the people I do.”

Wyeth’s art stems from a love of home and a love of the commonplace:

“The hardest thing for a young person is to see romance in the surroundings of the commonplace. We cease to see the quality of an electric stove against a window. If you believe in it, have a love for it, this specific thing will become a universal. Of course, the mundane has got to have a life, but it all depends on how strong your imagination is.

Wyeth’s painting is a mixture of paradoxes: hardness and love, harsh realities and comforting landscapes. It is, as Pete Candler puts it, “the human longing for home and the melancholy alienation of human existence.” But, Candler also points out, Wyeth understood the deepest level of reality: “reality is itself magical.” A world created as good that deserves a response.

This, with Wyeth’s help, is what I have come to see home as: a place of deep metaphor and goodness. If I truly love my home, I will not just love the beautiful, easy parts of it, the parts that overwhelm with grace. I will also love the toughness of it, the parts that are not what we might consider beautiful, and yet are real. Sentimentality is not my struggle with home; I can quite easily do that in my head when I am away. It is about returning and staying and embracing all that comes along with a place. In a sense, I am always returning home, both physically and metaphorically, always trying to creatively preserve it within my memory and writing.

If I truly love my home, I will not just love the beautiful, easy parts of it, the parts that overwhelm with grace.

I perched on the faded front porch, staring at the tattered auction sign across the street, in a place I had avoided for the past six years but found myself happy to be back in. Crunching one of the sweet pickles my grandmother made, I let the juice trickle its salty path down my hand to wrist to forearm before wiping it off. The sounds of a sputtering lawn mower, spring bird, and buzzing gnat serenaded the muggy, warm air. Grandfather bent under the hood of his old Chevy, while my father busied himself with the engine; mother and grandmother made lunch inside. I couldn’t help but feel like a child again, spending a summer day at their house, playing hide and seek at the railroad tracks, picking blackberries that would stain my mouth dark red. This was home. I think maybe this was what Wyeth was trying to get at the whole time.