I am from El Paso, Texas.

The rest of America’s hope settles in its dust. It comes blowing down from both sides and settles right there in the sand like many an American ideal barred by the border. Driving into El Paso on Interstate 10, it feels like the city may never come, until suddenly, after eight hours of a few ghostly railroad towns, oil rigs, and Dairy Queens, it finally happens. Not just seen from the road, it is felt—like a drink of water, it comes as a relief.

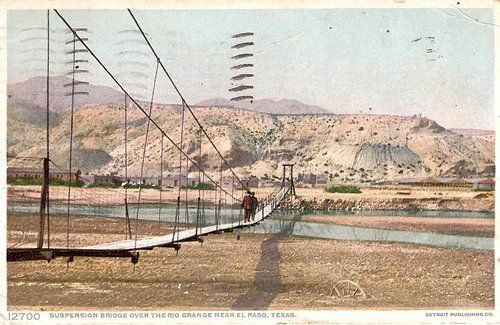

El Paso was planted at the base of the Franklin Mountains and watered by the Rio Grande. I suppose it remains to be settled whether the United States reaches its hand into Mexico or if Juarez is stretching its legs onto American soil. Today a fence traces the line that river’s water once drew. Distance makes it easy to forget what El Paso lacks compared to its Texan sister cities, yet proximity makes its socio-economic dominance over Juarez blatant.

If something new and fresh comes their way, the people of El Paso will take it gladly, but there’s no telling if it will last as long as the traditions that make the city move, rambling and rumbling like a Ford truck on one of its ranch roads. True, in the last ten years the city has leaped in progress, but still this happens at the slow pace for which the city is famous.

El Pasoans share the in the pride Texans are infamous for, but distance from their fellow comrades imbues the pride with a simple-minded charm. It’s felt that “the stars at night are big and bright” and that the “sage in bloom is like perfume”, but not with the same fervor.

Nobody complains about the climate. For some its consistency adds to El Paso’s charm. For others the pleasure of perfect weather is pacifying; sunny days run into each other, whole seasons passing without a change of shirt. When rain finally falls, it falls hard, breaking the parched ground open and forcing it to succumb.

It goes without saying: postcards from El Paso are sent with irony enclosed in the stamped envelope. Despite all of this, its unique offerings satisfy.

I was raised in this place.

A sporting goods salesman, my maternal grandfather worked Wilson’s southwestern territory, eventually relocating his family from Chicago. A truck driver, my paternal grandfather cruised I-10 carting goods east from California also eventually pitching the Ritchey tent in El Paso. My parents met at the state university in town, got engaged three months later, and married three months after that.

I won’t forget our stucco house on Guthrie street. At dusk the light would catch Guthrie’s street sign, shooting glares through my bedroom window, affixing the memory of that sight at the front of my memory. Oakbridge and Rockwood didn’t puzzle me, but Guthrie, what was that? I’ve never known how to shut my mind off when it settles into speculation, an unrelenting eagerness to question everything. I exhausted my parents with questions. But answers to the real questions, not why a brain freeze happens, or why the stop lights are red, yellow, and green, but the questions with consequences, those questions I sometimes wish went unasked. As for that Guthrie street sign, it’s fun to think of it as a signal from the “Dust Bowl Troubador” himself, picking me out early on, singing to me before I had answers that hurt the both of us.

To pass the time, my young family piled into our truck to take nighttime drives around the historic district, a hodgepodge of old ranch style outposts and mansions. Peeking in windows, I’d imagine how the owners traipsed around; with each lamp lit, a story unfolded in my mind. We’d conclude with a stop at St. Anthony’s Monastery, “set upon a hill to light the way,” but the dark, gated grounds and towering cathedral paired with crumbling headstones at Concordia cemetery on the horizon terrified me. My infrequent mass attendance and minimal acquaintance with the sacraments didn’t help. Lunch time stories of First Holy Communions in white dresses left me keen to understand. A Swedish Lutheran in a place where most of my school friends were Catholic, it was difficult to situate myself in the crowd, but I learned and I was bolstered.

By the time I started high school, it seemed most of the girls had forgotten the feeling attached to those white gowns, that is, until it came time for them to put another on for their quincaneras, a young Hispanic woman’s entrance into womanhood. A quincanera is one occasion (of many) to gather friends and family for food and fun.

Life was leisurely. Everything began after schedule because there was no rush to be anywhere else. The expression “our door is always open” was well-lived, and when I crossed a doorstep, I was met with open arms. Truly, the hug was the handshake even between strangers.

Like most suburban cities, El Paso has its share of strip malls, a uniform assemblage in every subdivision. But because of its felt isolation and a hesitance from large chain stores to move in, these strip malls are packed with small locally-owned businesses. I had a favorite tiny taco joint, tamale joint, fajita joint, margarita joint and guacamole joint. For fifty years my grandparents have dined at Avilas’s, a family-owned Mexican restaurant. The fixtures remain unchanged: rod-iron lamps, bright upholstery, desert landscape paintings and heavy ceramic plates. You can expect it to stay that way if the last five decades are any indication.

These memories make me eager to defend it. Yet I was unwilling to commit. I was authenticated there, working to prove myself as much as the city works to make a mark on the map, and once I had, I went away. But when I come home, I’m a prodigal welcomed with a “Bienvenidos!” as if I’d never left. It’s an unexpected return on an investment that ended the day I left.

A long absence hasn’t lessened my fervor. Ask me where I’m from and my heart swells with pride, pride in the mountains, the river, the sunsets, and even the grime that builds up from the hope that settles in the dust.