“If we are to love our neighbors, before doing anything else we must see our neighbors. With our imagination as well as our eyes, that is to say like artists, we must see just not their faces but the life behind and within their faces. Here it is love that is the frame that we see them in.”– Frederick Buechner

I am an unabashed people-watcher. I don’t mean to be rude; I’m just fascinated by humanity. I furtively watch people in coffee shops, bookstores, grocery stores, in their cars (at stoplights), and so on. Just the other day, I took a hellacious glucose/insulin tolerance test and was in that waiting room for a good six hours. I packed a good book, but I kept peeking over the pages at the blank stares of others in that medical purgatory.

A Hispanic male nurse called my name every hour to draw blood. Along with light blue scrubs, he wore a black yarmulke bordered by silver stars of David, and cobalt blue Hebrew tattoos were etched onto his forearm. I was utterly intrigued – people-watching up close and personal – and we chatted while I looked away from the needle. When I looked back, I noticed he had scratches on his face. He winced at one, laughed, and said, “I got these on Hanukkah, can you believe that? It started out well, but it didn’t end so well.” The writerly side of my brain was madly screaming, “What IS his story? He’s a story to be written!”

I love photographs of people for the same reason. I pore over photographs on Flickr almost daily, and within that community I discovered a beautiful book that captures the essence of friendly people-watching: The Day-to-Day Life of Albert Hastings. The photographer, KayLynn Deveney, and her husband noticed Albert as they walked to and from their basement flat and the city center in southern Wales every day. The old man often leaned against his building, his quiet yet lively presence contrasting the architecture’s decay. He watered the gardens to sustain life. Others might have overlooked this lonely man, but KayLynn was attentive to a light in Albert’s face that made her want to know him.

She felt a bit shy to transition from watching to meeting Albert, but she mustered up the courage and he greeted her warmly. Soon after, she asked if they could work on a photographic project together. As they got to know one another, she noticed his daily liturgies – how he thoughtfully organized his belongings and his time. And through conversations with Bert, she realized that their perceptions about photography differed. To allow Bert to converse with her camera, she asked him to jot down captions in a pocket notebook. KayLynn’s empathetic, honest photography and Bert’s thoughts became a dialogue that eventually grew into this book.

In the introduction of The Day-to-Day Life of Albert Hastings, KayLynn states:

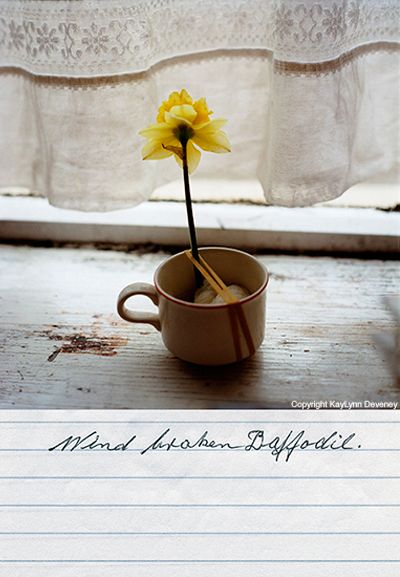

I believe photographs of our possessions and domestic patterns can be portraits, just like the photographs of our faces.

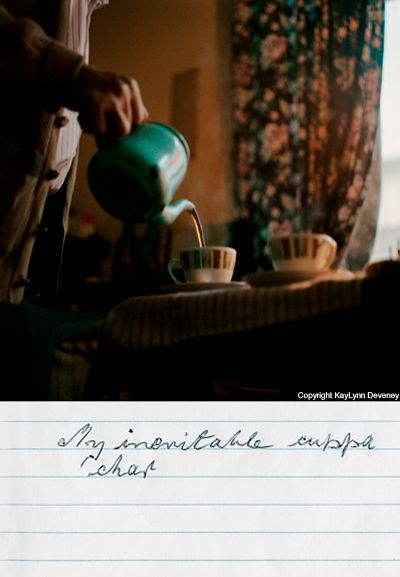

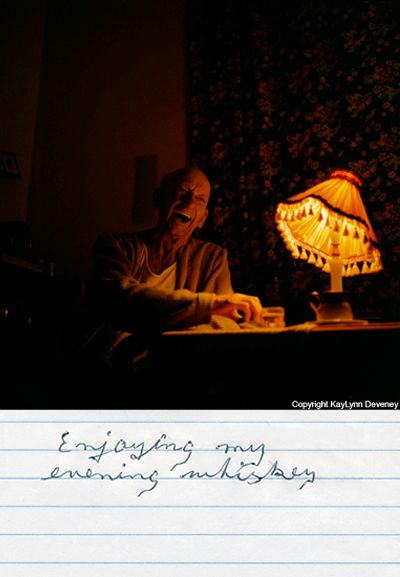

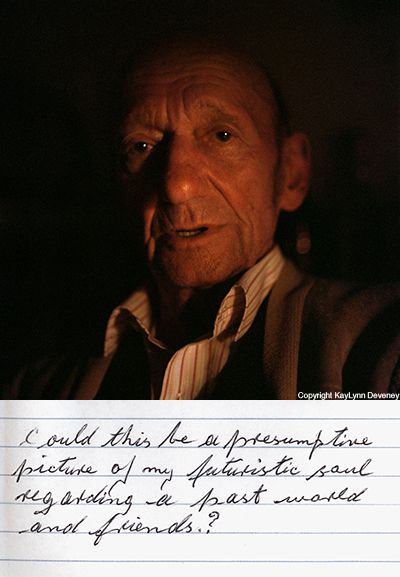

This truth shines forth from images of Bert, his small home, and his neighborhood. He poured “his inevitable cuppa chai” into two cups, not one. He salvaged a wind-broken daffodil by stabilizing it to a mug with a rubber band. He laughed into golden lamplight enjoying his evening whiskey. He looked straight at KayLynn’s camera and wrote, “Could this be a presumptive picture of my futuristic soul regarding a past world and friends?” He folded his pajamas on his bed. He washed his socks and hung them on a coat hanger to dry. He placed a Fedora on his head to go out. Birds alighted his hand. He listened to the radio. Interspersed within the photographs are Bert’s poems, drawings of his clock hobbies, his handwritten TV schedule, and old photographs of his late wife, daughter, and grandchildren. Each smooth page in the book seems to literally speak of Bert’s hospitality, compassion, simplicity, comfort, humor, humility, grief, and dignity.

Albert reminds me of my late father-in-law, who also lived a quiet, lonely life. They even resemble one another, and both served in their country’s military. My father-in-law’s primary joys were his dog, Twit; mystery novels; his cowboy boots for kicker dancing; Blue Bell homemade vanilla ice cream; and dinners with me and his son, where he always ordered salmon. His Air Force medals hung on the wall. These details and daily rituals of my husband’s father, and those of Albert’s life, are important and noteworthy because this is how they lived, and every life matters.

KayLynn documented Albert’s day-to-day life with creative tenderness. They collaborated to create both friendship and art. It inspires me to ponder the possibilities of our interactions with strangers outside of our social comfort zone. We could start by befriending and serving them, then really see our neighbors through art – perhaps by photography, recording or writing their stories, or making a short documentary film. Or we could simply talk with them, know who they are. Our society tragically tends to ignore the lonely, poor, and elderly.

KayLynn reminds us of this again in a beautifully painful portfolio entitled “Edith and Len.” She began photographing Mr. and Mrs. Crawshaw shortly after they moved into a Welsh nursing home for their combined failing health, though Edith was in slightly better shape at age 93; her husband was 92. These photographs are difficult to view just as any nursing home is difficult to visit.

I used to visit a couple in a nursing home around the corner from our church that reminded me very much of Edith and Len. Billie and Allan lived in adjacent rooms, but every Sunday morning I found Allan seated in an armchair at the foot of his wife’s bed watching a church service on TV. I will forever associate that elegant woman with Psalm 91 – it was quite possibly her favorite piece of poetry ever. She requested that I read it every Sunday morning and always said, “See? How can we fear anything?”

Yet I felt their displacement like the weight of an anvil on my shoulders, and I feel this same sense of the mourning of home in the portraits of Edith and Len. But I also see the beauty of the elderly – every line and wrinkle of age traces poems of the joys and tragedies they’ve lived, and the wisdom planted deep within. One of my favorites in the “Edith and Len” portfolio is a sad photograph of Edith’s beautiful old face, her furrowed brow looking upward seeming to say, “O Lord, how long?” KayLynn kept diary entries for this project and that particular photograph’s entry reads:

October 30

The seasons are changing today.

The sky is darker and more wet.

The leaves are dancing around the

streets. Edith asked me today if I

could imagine what it’s like to sit

there all day, every day, the way

she did. I thought, I am desperately

trying to imagine it.

Certainly, nursing homes are full of tragedy: neglected residents, suffering, and an unchosen home. But we cannot and should not look away from the tragedy depicted in KayLynn’s work. It is a powerful encouragement of how to live better: visit nursing homes often, or when you’re able, welcome elderly family into your home. But regardless of what we’re able to do, we must not forget anyone who lives and breathes in this world. Albert’s, Edith’s, and Len’s stories were written before they were born; it’s our job to learn their stories, share, and do likewise.

Click on the thumbnail to see the full-sized image.