In 2016 an American writer pauses at his keyboard. He is working on a project, but this morning he has decided to put it aside to write a letter to America. The letter is his attempt to re-court a prodigal country, and while he’d love to follow John Steinbeck’s lead in Travels with Charley, devoting a year to search for her and dedicating an entire book to describe her, he is hoping the morning’s work will convince his dearest to return to him and be the country he knew.

What he needs to do, he is convinced, is write about Donald Trump. He needs to explain to his beloved America the cost of her flirtation. In this, he hopes to channel Mark Twain’s Dr. Robinson from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Like our writer, Dr. Robinson refuses to stand idle as imposters deceive those close to him. While the King and the Duke pose as the late Peter Wilk’s brothers, attempting to steal Wilks’s fortune from his nieces, Robinson steps forward and declares the King and the Duke impostors, frauds, tramps. Drawing upon his long-standing friendship with the girls, Robinson pits his character against the character of the King:

“I was your father’s friend, and I’m your friend; and I warn you as a friend, and an honest one that wants to protect you and keep you out of harm and trouble, to turn your backs on that scoundrel and have nothing to do with him, the ignorant tramp . . . He is the thinnest kind of an impostor—has come here with a lot of empty names and facts which he picked up somewheres, and you take them for proofs, and are helped to fool yourselves by these foolish friends here, who ought to know better. Mary Jane Wilks, you know me for your friend, and for your unselfish friend, too. Now listen to me; turn this pitiful rascal out—I beg you to do it. Will you?

With minor substitutions, the Dr. Robinson’s plea is precisely what the writer wants to say to America. It is an appeal from the heart predicated upon character and love—both exhausting and cathartic.

***

At least I imagine this to be a typical scenario, since virtually every writer I follow has commented upon the Trump phenomenon.

Many of these pieces have been memorable—baseball writer Bill James’s cranky rant at The Federalist demonstrates how far the impulse has travelled, and David Brooks’s gloves-off, governing cancer thesis typifies the urgency and tone. But most remarkable is how, for my writer (and by implication, for these real writers), the similarities between Dr. Robinson’s situation and his own extend to their results. The Wilks sisters dismiss the doctor in the most unfortunate manner—Jane votes for the King by entrusting to him her inheritance of $6,000—and all Dr. Robinson can do is affirm that he told everyone so: “But I warn you all that a time’s coming when you’re going to feel sick whenever you think of this day.” The writer, meanwhile, if he lives in a state with an early primary, is left to watch America pass a bag full of delegates to the real estate mogul-turned-politician from New York.

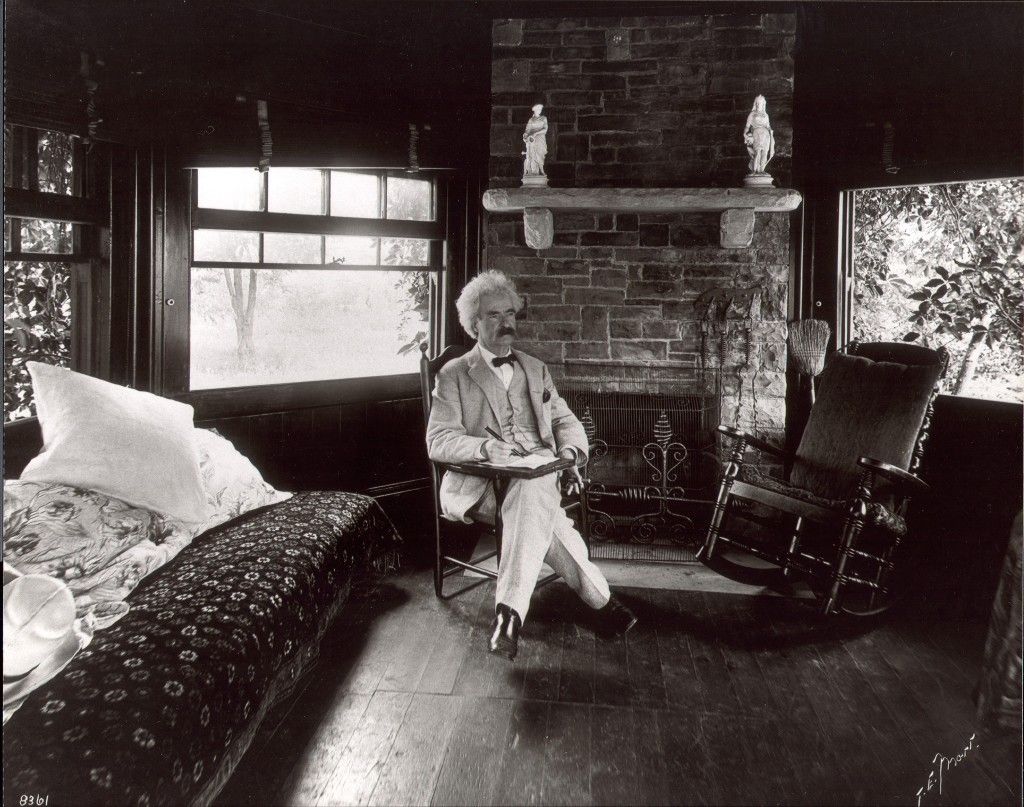

My writer’s primary trouble is not the nature of his opinion or even his desire to make an appeal, but that his strategy mimics Dr. Robinson’s tactics, not the tactics of Dr. Robinson’s creator, Mark Twain. The doctor is correct, but he is frustrated. His good-natured and rational appeal to character is powerless before a pair of crooks who do not abide by his rules of conduct. Twain, on the other hand, always managed to subvert such maneuvering. His arrows flew true and his barbs held tightly, maintaining their grip long after killing their target.

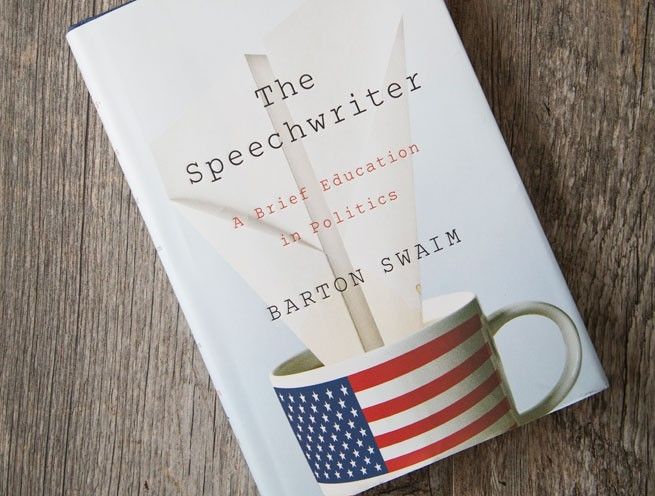

The legacy of Mark Twain’s satirical strategy is evinced in Barton Swaim’s memoir, The Speechwriter, in which Swaim ably uses humor to reduce a public figure to his proper size. In this case, the public figure is Swaim’s old boss, former governor of South Carolina, Mark Sanford. And while for any reader of The Speechwriter, Sanford’s political standing will shrink, the book will assuredly inflate his status as a comic figure. No matter what else he achieves, Sanford will live in my mind as a comic grotesque.

Swaim’s sketch of his boss had me shaking with laughter, fearful I’d wake my wife. The governor was so cheap that his staff’s Christmas presents were re-gifted trinkets, “…a Christmas ornament bearing the words, ‘Merry Christmas! Love, the Peterkins,’” so verbose he used “indeed” to cover over poorly phrased nonsense, “Jefferson and the founding fathers indeed founded this nation on the notion of limited government,” and so vain that “he apologized to his mistress and to his family…in that order.”

Yet as funny as this material is, its value arises primarily from the insight it provides. Swaim’s book, published well before the 2016 election, has shaped my view of Donald Trump’s triumphs this primary season. And while the tower of Trump might be larger-than-life, Swaim’s point of view has helped me see him less as an anomaly and more as a sharply outlined type.

Swaim articulates the particulars of this archetypal 21st-Century Politician in his concluding chapter, pointing out that high-level politics cater to a certain kind of person: “People like Tom Sawyer [here he quotes Catherine Zuckert], serve others not for the sake of others…They serve because they glory in receiving glory.” Applied without exception the claim is unfair, and Swaim recognizes this and accounts for its varying degrees. But Swaim also observes that these elected officials have “sought and attained high office by innumerable acts of vanity and self-will.” In this, our democratic process, which can variously resemble the election of a prom queen or the selection of sides for schoolyard football, does not always feel like governance. And it certainly doesn’t feel like service.

Certainly, a person might enter politics out of a desire to advance a good cause or serve a constituency—local elections can feel purer in this way—but the process sifts candidates until those of only a certain mettle remain: the kind of person who enjoys the glory that attends being elected and getting things done. “What drives him is the thirst for glory; the public good, as he understands it, is a means to that end.” In this sense, Swaim’s depiction is wondrously similar to the description of the Pharisees in the New Testament, the ones Jesus excoriates because they “love the best seat in the synagogues and greetings in the marketplaces.” Not wanting particularly to vote for Pharisees for President, I wonder: can’t we choose someone else? Can’t we find the humble candidate and uphold him or her?

Unfortunately, in answering this question, Swaim brings us more bad news by reminding us that, “Successful politicians are people who know how to make us think well of them without our realizing that that’s what they’re doing; they know how to make us admire and trust them.” If Swaim is right, then the candidates who strike us as selfless and trustworthy are likely the most adept at using their self-will to hide their vanity.

***

What, then, is my despondent writer to do? To accept the truth of Swaim’s final thesis could invite despair: they’re all miserable! They’re all selfish, glory-seeking, unctuous Pharisees! And America is falling for their wiles! But to temper this truth by adopting Swaim’s approach, the approach of the humorist, is to see that truth in perspective.

This is where Swaim’s memoir moves beyond depressing description and provides capable guidance. While laughter is a familiar political tool, used to imitate Alaskan governors and make modest proposals, the laughter Swaim induces represents more than a typical gag or criticism. He’s not just mocking ineptitude or dishonesty or bias—though he does those things—and he’s not just laughing to keep from crying. For Swaim, his laughter is a declaration that he recognizes the farce, that he will not be duped again into trusting the 21st-Century Politician.

I say duped again because the key element of Swaim’s experience is that he plays the stooge for his own joke. As exaggerated and vain as his boss clearly was, Swaim trusted this governor. This was his mistake. Now, while Swaim can’t change the man, he can choose how to see him. He can see him for what he is and he can choose not to trust him.

And the best way to assert his lack of trust, to inoculate himself against the 21st-Centry Politician, is to laugh at him.

Yet while laughing at someone is essentially the definition of mockery, I would characterize Swaim’s laughing differently. It is closer to the laugh of self-deprecation, because it sees the truth—even though it is preposterous—and recognizes the truth for what it is. It sees that this preposterousness is partly our own doing, our own desire to hear what we want to hear and see our leaders as we want them to be.

***

Mark Twain claimed that his humor was a vehicle, not the purpose, for writing what he did. “If the humor came of its own accord and uninvited,” he wrote, “I have allowed it a place in my sermon, but I was not writing the sermon for the sake of humor. I should have written the sermon just the same, whether any humor applied for admission or not.” In this way Barton Swaim imitates the American master of satirical humor. His insights can give us the perspective we need during an election where humorists are straining to parody an already exaggerated reality.