I recently concluded that looking at art is a lot like visiting Staten Island: it really helps to have a guide. Like Staten Island, art does not disclose its secret loveliness to the casual tourist, breezing through the gallery like a Brooklynite through Staten Island en route to the Jersey Shore. To learn to appreciate art – or Staten Island, for that matter – one needs a docent, a guide who knows the lay of the land. I am a docent for Staten Island, but when it comes to art, I need help.

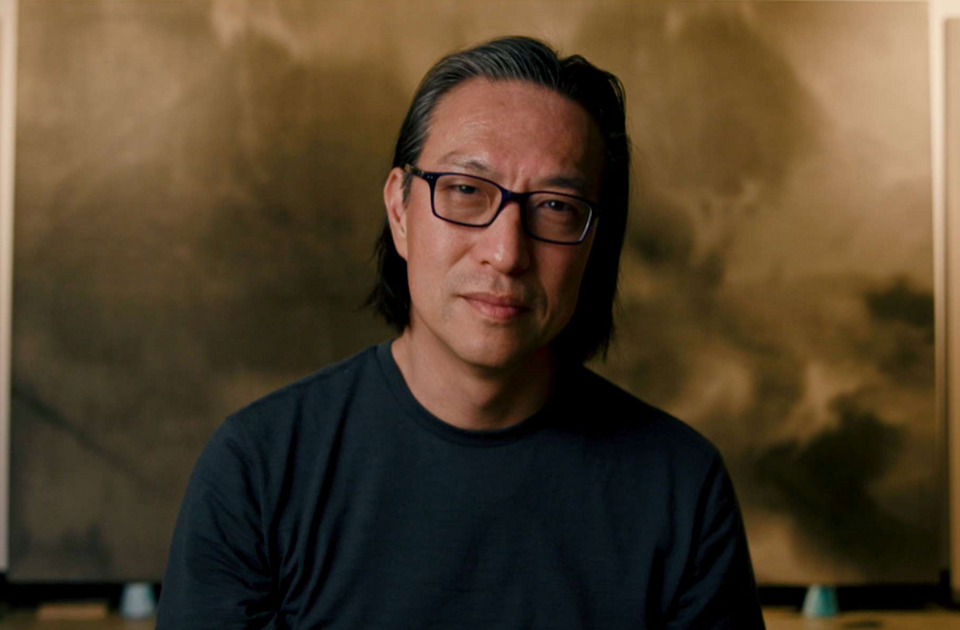

Through my work with International Arts Movement, I have the benefit of knowing many artists and creative catalysts who are willing to give of their time and expertise to help me grow in my approach to viewing art. I have no background in the visual arts, but friends like Mako Fujimura, Dan Siedell, Alison Stigora, Jay Walker and many others have taken time to patiently guide and instruct me in the art of viewing art.

(In addition to these conversations, Fujimura’s books River Grace and Refractions, and Siedell’s book God in the Gallery have been tremendously helpful.)

I have developed for myself an approach to viewing art that makes my trips to galleries and museums a source of delight and stimulation. I hope that, by sharing it here, I might help my fellow art novices have a more meaningful experience the next time they visit an exhibition.

First, I’ve learned that it is important to go into a show humbly. Decide before you walk in the door that you are not going to make quick judgments or dismissals of the works. I find that this is especially important with a lot of modern and contemporary art, which can often give a pedestrian primacy bias. (Warhol’s Soup Cans, for example, might have this effect. It’s easy to think you’re seeing it immediately.) Artists have spent time, energy, contemplation, and resources to create what you are about to see, and curators are deeply invested in what they place on the walls of their spaces. Give them the benefit of the doubt. I was that person who would actually say, aloud, while gazing at a late Jackson Pollock, “I’m not impressed. I could do that. What’s the big deal?”

Listen to me when I say that this is the height of arrogance. Don’t say that. Don’t ever say that.

The second point follows closely on the first: take your time. Do not meander quickly through a gallery or museum and think you have seen the art. If you have meandered quickly, you have not seen the art. Rather, stop in front of the work and gaze – gaze – at the work. Let your eyes rest on the piece for at least a few minutes. Scan it. Stare at it. Tilt your head to the side and stare at it again from a different angle. As in tasting fine wine, swishing the wine around your mouth and across your taste buds, viewing art requires giving your eyes some swishing time. Your eyes are your taste buds when it comes to art. Swish away.

Also, while I encourage people to attend exhibition openings, it is important to point out that the opening of a show is not the time when you will look at, or have a meaningful experience with, the art. The opening is for celebrating the artist. If you want to see the art, go back another day.

Thirdly, make notes. Bring a small notebook and note what you see. For me, this starts with noting the obvious. At my recent visit to Thrust Projects gallery, for example, where I viewed the current UNHEIM exhibition, I wrote in my notebook while standing in front of Valentin Hirsch‘s works on paper, “Elephants. Broken tusks. Multiple trunks. Realistic, but not real. Split, motion, splash. Precise. Landscapes. Mirror image of life and death. Black cloud. Black rain. Tragedy.”

I was describing what I was actually seeing on the paper. Looking at Daniel Domig‘s work in the same exhibition, I wrote, “Human images. Various details – some details, some amoebic. Copulating. Boxing. Violence. Human and skeleton dancing? No, having sex against a wall. Shrouded head. Woman performing fellatio on a man’s very large – phallic – nose, as an idea in a man’s head. Erotic. Uncomfortable.”

• UNHEIM, featuring works on paper by Valentin Hirsch and Daniel Domig, runs May 29-July 19, 2009, at Thrust Projects, 114 Bowery, Suite 301 in New York City. For more information, visit www.thrustprojects.com.

‚Ä¢ See a previous Curator article on Daniel Domig’s work.

This is not yet getting into what the work is saying. This is just what I am seeing. But as I wrote what I saw, I began to “see” more. Getting beyond the obvious discernible images, I began to draw some conclusions (which may or may not be what the artist intended, but by this point the artist is no longer in the picture; it’s about the art itself and the viewer’s experience of that art, or so Dan Siedell tells me.)

The last thing I do during a gallery visit is to walk back through the art one last time and do word association, writing down every word that comes to mind as I view the art. It was during this stage of my time with UNHEIM that the collaboration between two very different artists came together in a unified way: the words I was associating with each of their work were the same. Surreal… destruction… violence… haunting… tragedy… conflict… struggle… These words describe the “story” I “read” during my visit with both Domig and Hirsch’s work.

At this point, I have engaged with the art on a deep level. I am ready to describe my experience. The story I read went something like this:

The work is deeply disturbing. Hirsch’s work makes me think of how elephants are so regal and strong, yet vulnerable. The landscapes remind me of Africa, and the poaching of elephants going on there. This reminds me of the bigger issues facing global humanity, where the stewarding of the land that was mandated in Genesis 1 and 2 has become badly perverted. Looking at one particular portrait of an elephant head, drawn very regally, but with broken tusks and eyes that are indiscernible, lost to shadows, I was stirred to sadness, in the same way I am when I see an elephant in a circus. This was not what elephants were created for. They were made to be kings; instead, we have made them clowns. These pieces speak to me of destruction and tragedy. But Hirsch is not talking about elephants here. Elephants are a metaphor for something else, I’m sure. As I think further about the kings/clowns idea, I think of humanity. Is humanity what it was created to be? Not by a long shot. We were made in God’s image to be kings and queens. Instead, we are clowns. Worse, we are slaves.

Domig’s work is likewise evocative of sadness and longing, but not in quite the same way. In his work, there is a wrestling match between reality and the psyche. Some images remind me of a passage in the Bible, where St. Paul says, “Who will save me from this body of death?” There is a sense of being weighed down by an unseen burden, or enslaved by something intangible, yet very real. I see in many of the images a clear man, a central character of the piece, but with ideas or fantasies or struggles that inhibit him from being fully alive. He, too, is a slave, perhaps to his past, or to his memories, or to his unfettered animal instincts that threaten to dehumanize him. He is haunted by something he can’t quite shake.

Both artists’ work caused me to think deeply about the human condition – and not just humanity in general, but my own humanity. Am I living as the royalty I was created to be? Or am I living as a slave? Do I have a monkey on my back, or have I managed to throw aside everything that has entangled me? Do I continue to dance with a “body of death,” or do I take my thoughts and imagination captive to that which is good, true, and beautiful?

Viewing art is a very personal experience, if you will let it be so. But like many vessels of beauty or truth, there is no Reader’s Digest version. Without spending time with the work, you might walk gaily through the gallery, muttering to yourself “I don’t get it,” because you simply didn’t give the art an opportunity to give “it” to you. I spent nearly two hours with approximately thirty small works on paper, and the experience I had was profound. What a gift art is, if we will receive it as such.