T. is a rebellious teenager who wears a thong poking above her low-slung jeans and a zebra bra flashing through her top. Buck is a biker who watches porn and crushes cigarettes in his son’s muffins, which he mocks as “homo-made.” Alice walks out of the 1950s and all over everyone in her high-heeled shoes. And they all are really the same woman: Tara, a beleaguered mom who suffers from Dissociative Identity Disorder, which splits her personality into T. and Buck and Alice. “Having multiple personalities is like hosting a kegger in your brain,” sighs Tara. “Only you’re passed out cold while everyone else is trashing the joint.”

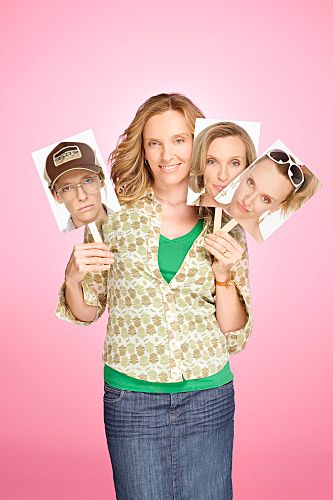

United States of Tara, just premiered on Showtime, could be a gutsy look at the confusion of human identity – if the producers use Tara’s split personalities as more than a plot device. It boasts a starry cast of Toni Collette as Tara, John Corbett as her long-suffering husband, and Rosemarie DeWitt playing almost the same self-righteous sister she played in Rachel Getting Married. Diablo Cody writes and produces it, with Steven Spielberg as consulting producer.

The show so far has explored the question of whether Tara’s “alters” are really her, and suggesting that maybe all of us, on some level, are a mess of different identities. The writers put this idea in the big mouth of a vacuous vitamin salesperson whose house Tara is redecorating. When it becomes clear that Tiffany knows the gossip, she tries to reassure Tara: “I kind of feel like everyone has it, you know, a little bit. Like in the course of a day, how many different women do we have to be? Like ‘Work Tiffany’ or ‘Sexy Tiffany’ or … ‘Dog Owner Tiffany’!”

The thought is suggested more seriously when Tara is talking to her therapist and says she worries that her husband only wants to have sex with the alter identities but not Tara herself. The therapist says people want what they can’t have.

“He can have me,” Tara says.

“He can’t have all of you.”

“The alters? They’re not me.”

But are they? The prim Alice tells Kate, “I want to let you know that even though I deeply disapprove of the way you carry yourself, your mother loves you very much.” She means that Alice disapproves of Kate but Tara loves her anyway; but Tara – when she’s in full possession of her true identity – deeply disapproves, too. She just doesn’t know how to say it, so Alice says it instead.

Maybe we all adopt different personas to face different situations. The show seems to suggest this in the first episode, when we see alternate identities echoed in her children. Her son is a soft-spoken, sweater-wearing, sensitive kid. Her daughter is a rebellious punk-ass with a swathe of blue hair and chains hanging off both her army fatigues and her boyfriend. But it’s impossible not to see an echo of Tara’s alternate identities when her daughter has a dance concert and is suddenly transformed into a pirouetting china doll, and when the soft-spoken son suddenly starts pummeling the pierced boyfriend.

The paradoxical wisdom of insanity comes through, too, when Tara’s insanity is more in tune with reality. Tara’s alters say the true things no one really says. Buck says that Marshall is gay, Alice says that Katie is a slut and that Marshall’s teacher (Tony Lane) picks on the nerdy students because he never fit in himself.

Movies and TV usually use DID as a cheap plot trick – to create the surprise ending where we find that the villain and the hero are the same person. But DID is a dark disorder, usually developed to cope with shattering childhood trauma. The alters do emerge when the real Tara can’t cope. T. comes when Tara doesn’t know how to relate to her daughter. Buck comes when Tara needs to drop-kick Kate’s abusive boyfriend. Alice comes when it’s time for chaos to stop running their lives.

But DID develops when you experience a shattering trauma that you can’t escape except by becoming someone else. So far, there’s nothing about Tara’s life that is harder than anyone else’s. Her daughter is your average rebellious teenager but her husband and son are saints. The show hasn’t hinted at a traumatic past and if there was one, Tara’s put-together sister Charmaine (Rosemarie DeWitt) doesn’t seem to have shared it. There’s a moment when “Dog Owner Tiffany” suddenly blurts that she was abused as a child to draw the attention from Tara to herself. The moment is supposed to be mocking but many people who suffer from DID were abused as children. Was Tara?

Instead of just using DID as a plot trick to let Collette to show off her acting skills, United States of Tara has an opportunity to show the side of human identity – not just Tara’s but everyone’s – that’s laced with darkness and deep confusion. If they can show the darkness while still depicting the journey towards clarity, this could be a truly thoughtful show.