Opera in current American culture is passionately loved by a few and generally misunderstood, feared or even reviled by most others. Its complexities can require specialized knowledge or a willingness to set aside certain expectations to wholly appreciate the art form, but it is at its heart deeply human, with the power to move us in rare and unique ways.

In T.S. Eliot’s essay “Poetry and Drama”, he compares the ability of poetry and prose to express our deepest feelings:

“It is a function of all art to give us some perception of an order in life, by imposing an order upon it. The painter works by selection, combination and emphasis among the elements of the visible world; the musician, in the world of sound. It seems to me that beyond the nameable, classifiable emotions and motives of our conscious life when directed towards action – the part of life which prose drama is wholly adequate to express – there is a fringe of indefinite extent, of feeling which we can only detect, so to speak, out of the corner of the eye and can never completely focus; of feeling of which we are only aware in a kind of temporary detachment from action . . . This peculiar range of sensibility can be expressed by dramatic poetry, at its moments of greatest intensity. At such moments, we touch the border of those feelings which only music can express.”

The comparison between the music of great poetry and the music of opera is an apt one. Reading Shakespeare silently on the page can be like looking over an opera score; reading a soliloquy out loud may be similar to listening to an opera recording; but these pale in comparison to Shakespeare alive on stage or opera seen and heard in its true context. In other words, there is more being communicated in opera than the basic plot points of the story. The most critical elements of the drama are being expressed by the music in its dramatic context. The elements of stagecraft, acting, the concerted efforts of the orchestral musicians and the glory of the human voice all combine to communicate to minds and hearts and bodies in a way that can transport us.

But the main difference between opera and straight theatre is that the performers sing. The human voice developed to its highest capacity is made up of powerful vibrations that resonate in the bodies of the listeners as well as the singers. Some critics have argued that part of the power of opera to move us is related to the intense resonance created in order to fill a huge hall with a single human voice.

Listening to opera is a physical experience, but it also involves recognition and wonder. David Littlejohn, in his book, The Ultimate Art, says the human voice is “the instrument for which all others are metaphors.” He goes on to say,

“The awesome emotional power of great voices brilliantly used is, I believe, potentially far greater than that of any organ or violin, any orchestra or synthesizer, more compelling than colors on canvas or words on a page. There before you is a body, like yours, with a throat and larynx, like yours, drawing out of itself (as you may dream of doing, but cannot) sounds that vibrate and seize beyond the power of any nonsinging actor. It seems to me the most captivating and beautiful thing that a human being can do on a public stage in living time.”

But for all its glories, opera is a very complex art form that requires a huge number of factors to be working in perfect conjunction. The audience who will enjoy it the most will have the capacity to compromise and allow a suspension of disbelief to bridge the gaps between odd plot twists, body types that may not match character, stodgy directing choices, uneven singing – and allow themselves to dive in wholeheartedly, knowing that there will be moments of revelatory beauty that can transcend all difficulties. Littlejohn describes that kind of audience this way, “I do believe that an unusual ability and willingness to yield, to give in to a work of art is important: somehow to dissolve yourself and let the work include you.”

The Metropolitan Opera’s current production of “La Gioconda” is a prime example of an opera that requires some suspension of disbelief (as regards plot, in particular) but which amply rewards the listener with passionate spectacle and above all, glorious, almost inhuman sounds that pour over the audience.

‚Ä¢ Read more about the history of “La Gioconda”.

‚Ä¢ Buy tickets for the Metropolitan Opera’s production of “La Gioconda”, presented on October 2, 6, and 9 in New York City.

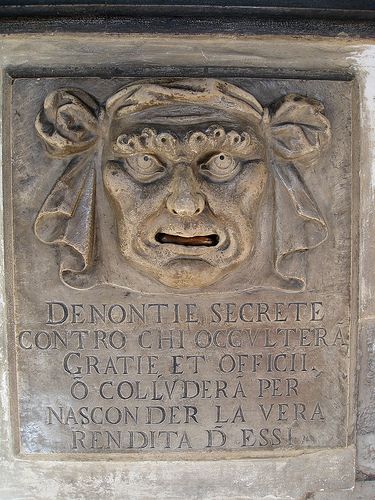

La Gioconda (“The Merry One”) premiered in 1876 with music by Amilcare Ponchielli and libretto by Arrigo Boito, and is based on the Victor Hugo melodrama, Angélo, Tyran de Padoue (“Angelo, Tyrant of Padua”). The opera is set in early 17th century Venice, a place of towering passions, crumbling power and moral decay. The story manages to jam in almost every imaginable dramatic plot twist – ove triangles, political and romantic betrayal, murder, sleeping potions and the like. But while the production provides plenty of romantic spectacle, aided by sumptuous sets of a towering ship and the Venetian palazzo Ca’ D’Oro, among others, this production is worth attending primarily for what you will hear.

While La Gioconda is famous for giving extensive singing roles to each of the major voice parts (soprano, mezzo, contralto, tenor, baritone and bass), in this performance it was the women who commanded our attention, both vocally and dramatically. This production is most noteworthy for the return of Ewa Podleŝ to the Met stage for her first performances since 1984. The Polish contralto has a cult following all over the world and her performance as La Cieca, the blind mother of La Gioconda, the Venetian street singer, begs the question why she has been so long absent from the Met stage. Hers is a voice which, while interesting enough in recordings, demands to be heard live in the acoustic space where it blooms and envelops the listener. When she first opened her mouth to sing in the opening scene of the opera, you could almost feel the collective shiver go through the audience, and after her aria they roared their approval. Listening to her voice is like diving into a deep well. The colors and tonal shape are wonderfully different from many of the other voices performing today.

The contrast with Deborah Voigt’s more frequently heard voice was rather startling, particularly in the first act, where her lighter, almost tentative singing at times seemed to be conserving energy for the later acts of the opera. The American soprano, who is making her mark as one of the world’s foremost Straussian and Wagnerian sopranos, initially sounded like a lighter lyric voice next to the dark colors and round tone of Podles, but in the stringent demands of Act IV in particular, the power and brilliance of her sound returned in full force. Her acting was passionate and impetuous throughout, conveying the downward spiral of La Gioconda’s extinguished hopes, and providing a dramatic foil for Olga Borodina’s regal and impassioned portrayal of Laura, the Genoese noblewoman. Their duet in Act II is one of the great vocal battles in opera and they did not disappoint, each matching the other for intensity and power of sound. The Russian mezzo sang with a wonderful combination of rich, dark color and cutting edge that rang out over the orchestra. Her no-holds-barred rendition of “Stella del marinar” produced a sustained ovation.

Next to the glorious singing and varied tonal quality of the women, the men performed competently, but for the most part did not shine vocally or dramatically. Italian baritone, Carlo Guelfi, as the Venetian government spy, Barnaba, was the most impressive, both for the warmth of his tone as well as the consistency of his acting, although neither matched the intensity of the three women. Venezuelan tenor, Aquiles Machado, sang ably as Enzo Grimaldo, the exiled Genoese noble and lover of Gioconda and Laura, but the size and tone of his voice, which occasionally sounded reedy on top, did not match that of either of his lovers, and his acting was wooden, making it harder to believe that these two women, in particular, would sacrifice so much for his sake. Bulgarian bass, Orlin Anastassov, making his Met debut as Alvise Badoero, the Venetian head of the Inquisition and husband of Laura, did not make much of an impression in his opening scene, but warmed up, both vocally and dramatically as the wronged and vengeful husband in Act III.

One of the highlights of the evening is a non-vocal one. The most widely known music in La Gioconda is the ballet scene, “The Dance of the Hours,” famously used in Walt Disney’s Fantasia. Christopher Wheeldon’s masterful choreography, weaving together classical and modern influences, and beautifully danced by Letizia Giuliani and Angel Corella, successfully banished the animated dancing elephants within a few bars of music.

The Met Chorus and Children’s Chorus both sang with power and precision, although the stage direction of the chorus was particularly static. It is disappointing to see a chorus of this ability not used more creatively.

With the length of the opera at a full four hours, including three intermissions, this production is not for the faint of heart, but for sheer theatrical value (the cheapest seats are $15) and an immersion in glorious sound and romantic spectacle, La Gioconda is not to be missed.