I am rarely romanced by agriculture.

I grew up in a rural part of Michigan, raised by a man who enjoyed working the land and a woman who learned how to put things up. Our home garden provided a yield that usually outlasted the winter: frozen beans, corn relish, canned tomatoes, apple butter. We had a modest number of chickens, a root cellar filled with potatoes and squash, and the occasional temporary livestock we were only allowed to call bacon or steak. All the modern fuss about locavoring is hard for me to understand – we didn’t do this to be novel or as some kind of grand gesture. It’s practical to till and plant and harvest.

I admit it; I’m always delighted and a little amused when city folk discover gardening and canning. But my days as a mocker and a scoffer are over, because, like Buddy the Elf, I’m in love, I’m in love and I don’t care who knows it.

Farm-fresh dairy. Homemade mozzarella, where have you been all my life? Even your byproduct is glorious: ricotta. Dear dairy, my heart beats only for you.

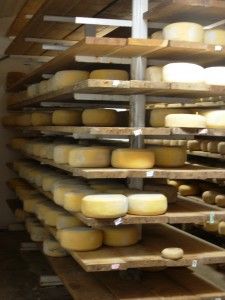

We met in Coopersville, Michigan, introduced by a mutual friend, Betsy Meerman. Former resident of my town, she went off to college and became a physician’s assistant by trade. But love brought her to a fifth-generation dairy farm, where she married Jesse the cheese maker. He’s a skilled craftsman, developing specialty cheeses that take advantage of the plentiful supply of raw, organic milk and cream produced by grass-fed, grazing cows. He makes a high cream aged cheese, Fait Gras, that is one of the most delectable things ever stabbed by a toothpick. She helps out by teaching classes on fresh cheeses and butter. One average day in May she suggested that I come and see.

If I had known what joys awaited me, I would have immediately jumped in the car and headed west. But I was busy. Perhaps the delay only made the union sweeter.

A friend and I finally made the journey one Saturday morning in October. The drive was metaphoric – we came across I-96 in a rainy haze that didn’t clear until we came off the highway. The fog lifted and the light shone down and before noon we realized that all of our lives we had been eating crappy mozzarella.

Betsy is a woman at ease with people. She is natural, friendly, and knowledgeable about the practical and scientific aspects of the cheese-making process. She has homespun star power, but even she could not compete with milk’s ability to combine with citric acid and rennet. The 30-minute mozzarella (recipe available for download here) took a little longer in the unheated cheese-making room on a crisp fall day, but once the curd came together, the process moved quickly. She stretched it until it was smooth and separated it into several small balls. She invited the class to come and finish the cheese.

Working this egg-sized, almond-colored glob was fun. The whey coated my hands as I imitated Betsy’s simple technique, reminiscent of folding socks. I set the perfect-looking ball on the platter.

I have been tempted by so-called fresh mozzarella before, in the specialty cheese case. It was disappointingly similar to the brick of cheese available in the regular aisle. It was edible, I thought, but not worth the money.

This was nothing like that. This was nothing like anything else I had ever called cheese. This was more than worth eating: it was warm, it was smooth, it was creamy, and yet had bite, grains of sea salt riding the wave of cheese perfection. It was the cheese that launched a thousand ships. It was worthy of song, or a crusade.

I’m not much of a sailor, or a singer, so when we returned, I started telling everyone of this glorious, simple process. But eating is believing, and when the time came and Betsy was in town over the holidays, she taught a home class.

A few bites in, I saw the eyes of a fellow student light.

“So, you’re telling me that every time I drink glass of milk,” he said, raising the cheese high, “I’m keeping it from its full potential?”

Smitten. And I can’t even put into words how he feels about the butter.