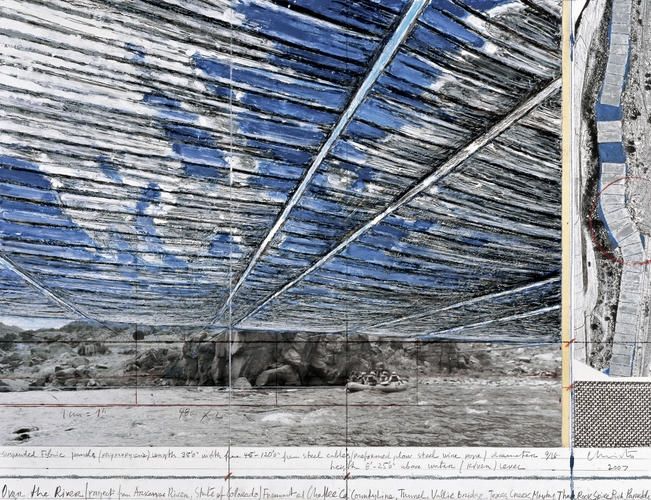

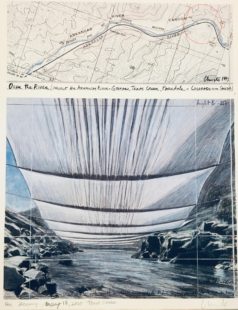

In 1992, Christo and Jeanne-Claude dreamed of a Colorado landscape transformed. The married New York artists envisioned the “Over the River” (OTR) project as a silvery canopy staked high above 42 miles of the Arkansas river and anchored to its banks by wire cables. The installation would hover over rafters below, tanned guides paddling groups in inflatable boats. As viewers glided down the rapids, they would pass in and out of shadow; the contours of clouds and canyons would dim and then brighten in their vision, revealing saturated panoramas of sunshine and red rock and scrub oaks and bighorn sheep perched on crumbling hillsides munching on grass. Seen from above, on the banks or the side of the road, from a helicopter, or perhaps while standing on the Royal Gorge suspension bridge that hung across a nearby canyon, the panels would shine and ripple in the wind, waves cresting beneath it, a luminous, shimmering ribbon.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude developed OTR over decades, planning the structure with engineers and scientists, and raising money to fund it by selling Christo’s original drawings, collages, and mock-ups of the project to collectors. Then came wooing the communities and politicians who lived in and presided over the region, and then jumping through, with the help of a team of lawyers, whatever flaming hoops these parties demanded. Next would come years of construction, the installation of the work, and finally, a two-week-long exhibition, with appreciators arriving from across the nation to experience the free open-air art work. Out of decades of planning, the work’s actualization would last just 14 days.

In theory, the project would provide jobs in a depressed regional economy: tourism, construction, security, recreation, even trash collection would be a boon to rural Coloradans who lived nearby. Christo’s team projected that OTR would bring over $150 million in new investment to the area. Promises abounded. Locals’ bank accounts would swell! Politicians would be crowned art lovers! Municipalities would be admired across the Internet! What could go wrong?

Christo and Jeanne-Claude had developed international acclaim for whimsical experiential art events that were ephemeral, technical, and expensive to erect. Still, they had somehow convinced the most bureaucratic cities in the world (Paris, New York, Berlin) to allow them to wrap monuments, buildings, coastlines, even islands in their custom fabrics, for the purpose of teaching locals to see familiar sites with renewed wonder.

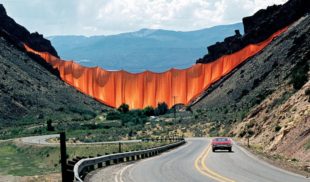

Having completed, in the early 1970s, a project in Rifle, Colorado in which they erected an orange “valley curtain” suspended between two mountains and crossing a highway, Jeanne-Claude and Christo may have felt optimistic, believing OTR would succeed easily, especially given their careful, years-long planning. They were wrong.

The first wrench in their plans, and the most devastating, was Jeanne-Claude’s death. Christo’s collaborator and wife, Jeanne-Claude passed away of a brain aneurysm in 2009, nearly twenty years into preparations for OTR. The two artists had met and fallen in love in Paris, when they were still in their twenties. According to Christo, they shared such a passionate first kiss that he broke a tooth. Right away, the artists began collaborating, realizing that they each had gained not only a lover, but also an artistic partner. They placed such a high value on their joint artworks that they often traveled to their sites in separate airplanes, so that if one plane crashed, the other partner could still complete their work-in-progress. Jeanne-Claude’s death, however, had arrived suddenly; the couple had been pursuing several projects across the globe when she died at 74 in New York City.

However much Christo had been devastated by the loss of his lifelong partner, he stuck to the plan: carry on. “Over the River” continued with Christo commissioning environmental impact studies, drafting proposals for permits from the necessary organizations, speaking at community meetings, and building a website and a marketing strategy. The approvals came steadily. However, each project always put up its own battle, and so Christo expected these negotiations with civil servants and neighborhoods to move at glacial speeds.

Then intense opposition arose against the project, and the community launched a war. Locals created an organization with the sole purpose of opposing Christo’s project; they called themselves “Rags Over the Arkansas River” (R.O.A.R.). They brought lawsuits against Christo and his legally-obtained permits; they asked for extra and costly environmental surveys, mistrusting Christo’s assurances that the many holes that would be drilled into the river banks would not damage their land or wildlife; they ignored the results of those studies and submitted appeals anyway for the lawsuits they had lost in court.

At public meetings, they shouted accusations: Christo was a liar, an outsider, a foreigner, (Though he’d been an American citizen since the ‘70s, he has a strong European accent). They berated local politicians for “drooling all over” Christo and doubted his intentions to hire locals. They balked at the drilling rigs, which would surely drive out tourists in the meantime. They claimed that if the traffic bottlenecked on the two-lane highway leading to the OTR exhibition, emergency vehicles would not be able to reach them.

Even when Christo offered to pay a retainer to hold EMTs in a helicopter for just this purpose, and even when Christo had spent $15 million of his own money on legal fees and federal surveys, and even when Christo fought R.O.A.R.’s lawsuits over the course of five years, appeal by appeal, the neighbors remained unconvinced; his artwork would surely kill them, their economy, and the landscape they loved, dammit.

Still Christo sought to make things work. In 2012, his publicity team told a Hyperallergic reporter, “Never before in the history of the National Environmental Policy Act has a work of art been subjected to this highest level of federal evaluation [as has Over the River].” He agreed to 100 mitigation methods to preserve the landscape, both during construction and afterward, even vacuuming up the very dust from the river basin, disturbed by his drills during the survey, into numbered bags, so he could return it to its native location during the project’s restoration phase. Ray Mark Rinaldi, a reporter for the Denver Post, called R.O.A.R.’s unrelenting opposition to Christo “the bureaucratic equivalent of waterboarding.”

Yet by 2017, Christo found himself twenty-five years into the project with no resolution in sight. Even if he started building immediately, the construction could take three years, and he was now in his eighties. Jeanne-Claude had passed, legal bills piled up daily, and billboards lined the canyon’s highway, proclaiming, “Just say NØ to Christo!” Exhausted, Christo blinked. He walked way. He gave up.

The opposition to OTR perplexed me as a Coloradan, particularly when the R.O.A.R. organization actually forced Christo and his estate to sign legal documents in 2018 stating that they will never resume efforts to revive OTR. I have lived in this state for ten years, and my in-laws owned a rafting company for years in the section of the Arkansas River where Christo had planned to erect his project.

My husband and I had attended a 2010 community meeting in a town in the path of the project, at a local restaurant that served hamburgers, ribs, and beer by the bucket. Twenty locals sat at a large wooden table, with Christo and his staff at the head, and Christo stood when it was his turn to speak. His white hair stuck out at all angles, as if he’d slept in a cheap hotel the night before—which he probably had. He was slim and bespectacled with an Eastern European accent, betraying his Bulgarian birth; he used his hands to accentuate his vision of what the project might mean for the people of the river basin, of the respect he had for the area’s beauty, of his desire to care for the environment.

Christo would later describe to KPBS reporter Angela Carone, in 2014, that he intended to make no money on the project and that he would charge no one to see it; I cannot remember his exact words from the meeting I attended, but I imagine he hit a similar note as the KPBS interview: “Nobody can own it. Nobody can buy tickets, and because of that, [viewers] have this enormous freedom and nobody can possess them.” In short, he hoped to offer his work as a gift to the people of the river basin, if they would accept it.

R.O.A.R. had formed before this meeting—though their website has been taken down, I can find evidence of their activities as early as 2006—yet the attendees at this hamburger, ribs, and beer joint had listened politely. No one argued, no picketing broke out, no protestors bellowed their dissent from the far end of the room. In fact, throughout all of the community meetings from the 90s through the 2000s, Christo remained composed, patient, even kind toward residents, compromising in every way to meet their demands. He viewed opposition as part of the process; the winning over of fiesty residents became part of bringing his art to life.

As R.O.A.R. gained followers and I continued to track the project in the intervening years, the group’s objections sounded more and more short-sighted (What about the infrastructure gains? The boom in tourism? The potential wildlife refuge Christo had promised to fund for local wildlife?), and even xenophobic toward Christo.

Only now have I gained perspective on Christo’s defeat.

For one, the artist’s most successful projects seem to be those that bring attention to landscapes and architectures that have become underappreciated by locals in their region; the people who benefit from the “new sight” of an exhibition are its nearest neighbors. But Coloradans are exceedingly proud of the untarnished beauty of their landscape; part of the Arkansas River valley’s allure exists in its isolation. Unlike many mountain communities in Colorado, where locals are outnumbered by out-of-town skiers and vacationers, towns along the Arkansas River have remained rural and underdeveloped, and residents like it that way, thank you very much.

In fact, in the case of the OTR project, the residents believed the primary beneficiaries of this “new sight” would not be the locals but the 400,000 tourists traveling in to take a look. It is as if these Coloradans had come prospecting for a stunning, undiscovered landscape and had found it, and now an outsider, uninvited, wanted to spill the secret. Making matters worse was the need for 9,000 holes in the river bank for anchoring the project’s panels, creating permanent scars on the landscape, perhaps the most striking “impact” described in the project’s 1,686-page Environmental Impact Statement (which was otherwise as easy to follow as a tax document). All this cast suspicion on the artist’s intentions.

And then there’s Trump. By which I mean, the “rural versus city” issue, dramatized in the last presidential election. Colorado, like many states that are primarily rural, is a state divided. Politically, nearly all of Colorado votes red except for the liberal northern cities—Denver, Fort Collins, and Boulder—where most of Colorado’s citizens reside. This means that rural Coloradans are always outvoted at the federal level.

I am not what Coloradans would call a “native.” I migrated here after college, which makes me a “transplant,” a status viewed with disdain by true born-and-raised Coloradans. Still, I can relate to rural Coloradans in their feeling of exclusion. The majority of our country believes that art, business and culture reside only on the coasts of our nation; those in the middle-states, and even artists like me who reside in middle-state cities, are not counted as significant to the cultural equation.

This is why I wonder what might have happened had Christo been a local artist instead of a big-shot New Yorker, if instead he had been native to Colorado, paying homage to his motherland. In art speak, “cultural appropriation” is defined as the majority culture stealing artifacts and customs from minority cultures for its own benefit. When we say it, we usually mean those qualities pertaining to skin tone and ethnicity, white versus brown, and the history of racism and oppression that has accompanied these unjust norms. “Cultural appropriation” becomes one more way for those in majority cultures to devalue and misuse minorities for the majority’s benefit. But I wonder if we might consider a broader definition of the phrase.

In this region, I wonder who needed the “new sight” of Christo’s work more—New Yorkers or rural Coloradans? R.O.A.R.’s objections to Christo centered on his outsider-ness, his unfamiliarity with their culture, their norms, and their history, which echoes the protests of minorities whose customs have been co-opted by the majority. Christo was the artist locals “should have heard of” and hadn’t; locals should have felt complimented to be courted by such an important person. Instead, residents felt what many in the middle states often feel: shoved aside by the coasts. Which is why R.O.A.R. began their campaign by casting themselves as the undersized hero standing up to a giant bully, an idea reiterated by the group’s spokeswoman Joan Anzelmo in a statement given to the Denver Post in 2017: “When ROAR initially filed the lawsuit, we characterized our battle as similar to David battling Goliath. We promised that ROAR would vanquish Goliath and ROAR did that with this permanent cancellation of the Over the River project.”

Naturally, the strong feelings of R.O.A.R. members do not mean that every resident of rural Colorado opposed OTR. In fact, a local magazine editor, Ed Quillen of CO Zine, defended Christo and mocked the opposition, writing in a 2010 article, “…This area has always been jerked around by outside forces…So here’s Christo, another outside force, a multi-national corporation if you will. And horror of horrors, he plans to put people to work hereabouts, while bringing more visitor money in. Damn those outsiders.” [Italics mine]

Quillen went on to point out that though the opposition had claimed that their valley would be permanently scarred by Christo’s project, the river basin had already been disturbed irrevocably. In fact, the very valley Christo had sited for his project had experienced disruption from home construction, the erection of power lines, and the presence of the locals themselves—not to mention what else had altered the canyon during more industrial seasons in its history, such as quarries, a railroad, and the two-lane highway cutting through the canyon. No longer could any resident claim that their landscape was the “narrow channel with immense cliffs on both sides” that Zebulun Pike struggled to traverse on horseback during his 1807 exploration expedition. To Quillen, where there are people, there is change, and to believe otherwise is to miss out on opportunity.

For his part, Christo would disagree with Quillen on fundamentals: Despite the short-term economic benefits the project would bring, Christo had not come to the Arkansas River as the commercial savior of the region. He actually opposes art with a message, calling it propaganda. In the KPBS interview, he explained, “Having been born in a communist country, and escaped from a communist country, I am allergic to art that is propaganda…art is something beyond that.”

Christo went further in the interview. The most consistent complaint to Christo about his project from residents themselves was why? Why are you doing this? They assumed they knew: OTR was a monument to himself, the whims of a megalomaniac millionaire. But his aim could not be further from that. “To do work of art,” Christo explained to the KPBS reporter, “…basically they exist because they are totally irrational. They are useless. The use of the project is only for beauty.”

For beauty alone, Christo came to the valley; for beauty alone, Christo emptied his pockets; for beauty alone, Christo courted opposition. To Christo, art is a useless, extravagant gift to be generously given and received. In the end, Coloradans said, No, thank you, Mr. Christo, we like our place just the way it is; go and make your art elsewhere.

At the close of the community meeting that my husband and I attended, Christo’s team raffled off a print of the OTR plans, and my husband won. Christo offered to sign it for him. With a wrinkled hand, Christo scribbled his signature in pencil and wrote, “To Jeremy.”

Though he never was able to actualize the mock-up depicted in that reproduction, we hung Christo’s work above our stairwell in our home. We received the gift.

###

Cover Image:

Christo and Jeanne-Claude

Over The River (Project for Arkansas River, State of Colorado)

Collage 2007

17 x 22″ (43.2 x 55.9 cm)

Pencil, enamel paint, wax crayon, photograph by Wolfgang Volz, aerial photograph with topographic elevations, fabric sample and tape

Photo: Andre Grossmann

© 2007 Christo

Except where noted, all images have been taken from christojeanneclaude.net

~

Sources:

https://christojeanneclaude.net/

https://www.kpbs.org/news/2014/feb/05/christo-talks-about-his-artwork-jeanne-claude-and-/

https://www.denverpost.com/2017/02/03/over-the-river-artist-christo-arkansas-river/

https://www.denverpost.com/2017/01/25/christo-over-the-river-project-halted/