Late every summer, a graffiti event takes place along St. Louis’ lengthy Mississippi River flood walls. Dubbed Paint Louis, the volunteer-led effort brings artists from around the Midwest to St. Louis, where they’re given a weekend pass to do as they please on short, defined stretches of those well marked walls. Last summer, though, something extra special occurred when monks touring in support of the Drepung Gomang Monastery arrived at the walls late one afternoon. Handling paint cans for the first time, the group assessed a short empty stretch assigned to another group, who’d finished for the day.

Sketching out the space with tentative streaks, two of the free-spirited and artistically inclined monks, Gyatso Thiksay and Jinpa Gyatso, painted a Tibetan flag on this rare, blank canvas of Paint Louis, as onlookers gathered. The pair gained confidence, it seemed, with each new can and color. Walking along the wall from hundreds of feet away, young people were amazed at the sight. One asked them, with both enthusiasm and complete seriousness, “Are you graffiti monks?”

In a move that neatly symbolized the impermanence of their sand mandala creations, the flood wall piece was painted over by the next morning, by graffiti writers who’d been previously granted that section of wall. If that buffing seemed bittersweet, it also symbolized the group’s gifts to St. Louisans over those two weeks. Their visit was transient, sometimes moving quickly from location to location, yet these small doses—both the planned and the spontaneous—brought their own inspirations.

Annually, rotating groups of Tibetan monks depart their in-exile monasteries, leaving their Indian homes to crisscross the United States with a small handful of goals. Most importantly, perhaps, they’re in the U.S. to spread the message of compassion and other tenets of their Buddhist faith. Key, too, is the need to raise money for their home bases in India, where their monasteries have resided since China’s takeover of Tibet in the 1950s. In the case of Drepung Gomang’s traveling monks, that means fundraising for a 3,000-person monastery, a heavy responsibility, but one that they bear with patience and grace, if limited English.

The Drepung Gomang monks visiting the United States on that year-long Sacred Arts Tour were split into two traveling parties. With their U.S. efforts centrally based in Louisville, Ky., one group traveled the Western states, with the other, eight-man group tackling the East. Each group’s itinerary is ambitious, with individual cities visited for as little as a few days or as long as two weeks. St. Louis was a stopping point for the six monks tackling the Western portion of the U.S. The group fills almost every day with public appearances, with just scraps of time left over for personal (if collectively undertaken) exploration of the city.

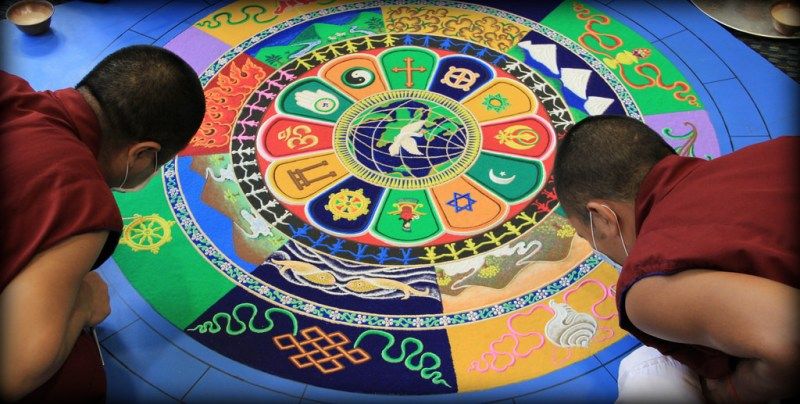

Headed up by their amiable leader, Geshi Tsewang Thinley, the six, along with an ever-present driver, undertook a variety of activities in St. Louis, while communally living in the home of a devoted Tibet supporter, Patty Maher. Over the course of their two-week stay, the group worked in a lot of contexts that are familiar to them, including the construction of two sand mandalas, which were each ritualistically swept apart after days of painstaking construction. For these public works, the monks displayed their skill at a pair of sympathetic homes: the Healing Arts Center, a hub of natural medicine practices and yoga, and Saint Louis University’s new home for international education, the Center for Global Citizenship.

At each location, the monks took turns working on the intricate peace mandalas, in between public lectures and gatherings. During those periods of intense, artistic effort, onlookers watched casually or observed intently, took photos and videos, and chatted with one another and with the monks during moments of rest. As is the custom, each mandala was destroyed by hand brooms and then taken to nearby water, featuring ceremonies enriched by chanting, horns and percussion. It’s hard to attend a sand mandala’s end without a touch of emotion, the message of life’s impermanence translated beautifully into this centuries-old artistic practice.

In many cities, the monks are hosted by peaceniks who involve them in a relatively narrow set of experiences. In St. Louis, though, the group was surrounded by some freewheeling supporters, which led to a few moments of interesting blending with local communities.

They went to the St. Louis Zoo. They canoed the Mississippi River. They sang and chanted at the massive Festival of Nations, while also exploring the urban wonderland of the City Museum, a sprawling former shoe factory that’s been transformed into the area’s most lauded tourist attraction. They caught a Cardinals baseball game at Busch Stadium. And in their last public appearance in St. Louis, after a cooking workshop in the basement of a South St. Louis church, they opened a set for the city’s popular Grateful Dead tribute act, The Schwag, in front of that group’s hundreds of surprised, ultimately supportive fans. By the time the group left town, my own role in their visit had changed from observer to participant, helping them secure a few of the more freewheeling experiences.

In offering many different looks to the St. Louis community that housed, fed and supported them, they provided a glimpse into their own humanity. In their matching robes and with limited English-language skills, it takes a while to determine the individual personalities of the traveling party. But over time, small cracks in that first impression of unanimity arrive, as personalities emerge and the monks’ own curiosities begin to shine, their humanity more apparent with each day. It was clear in those who attacked the flood walls with paint cans and those who watched and cheered them on.